The terminology of "intellectual property" goes back to the eighteenth century. But some modern critics of how the patent and copyright law have evolved have come to view the term as a tendentious choice. One you have used the "property" label, after all, you are implicitly making a claim about rights that should be enforced by the broader society. But "intellectual property" is a much squishier subject than more basic applications of property, like whether someone can move into your house or drive away in your car or empty your bank account.

The Oxford English Dictionary gives a first use of "intellectual property" in 1769, in an anonymous review of a book authored by a Dr. Smith and called New and General System of Physic, and published in a publication called Monthly Review (available here). The book review is extremely negative, essentially accusing the author of copying copiously from other writers--but adding errors of his own. Apparently at various points in the book, the author Dr. Smith refers to wonderful and enlightening experiments of his own that he claims have worked extremely well, but says that he doesn't want to bore the reader with his own work. The reviewer notices this disjunction between extensive copying from others and bashfulness about revealing actual work of his own (if indeed such work existed) and writes: "What a niggard this Doctor is of his own, and how profuse he is of other people's intellectual property!"

In the U.S. legal system, the use of "intellectual property" is often traced back to the case of William Davoll et al. vs. James S. Brown, decided before the First Circuit Court of the United States in the October 1845 term, which is available various places on the web like here. The court wrote: “[A] liberal construction is to be given

to a patent and inventors sustained, if practicable, without a departure from sound

principles. Only thus can ingenuity and perseverance be encouraged to exert

themselves in this way usefully to the community, and only in this way can we

protect intellectual property, the labors of the mind, productions and interests

as much a man's own, and as much the fruit of his honest industry, as the wheat

he cultivates, or the flocks he rears.”

The rhetoric is sweeping enough to make an economist blink. Is it really true that using someone else's invention is the actually the same thing as stealing their sheep? If I steal your sheep, you don't have them any more. If I use your idea, you still have the idea, but are less able to profit from using it. The two concepts may be cousins, but they not identical.

Those who believe that patent protection has in some cases gone overboard, and is now in many industries acting more to protect established firms than to encourage new innovators, thus refer to "intellectual property as a "propaganda term." For a vivid example of these arguments, see "The Case Against Patents," by Michele Boldrin and David K. Levine, in the Winter 2013 issue of my own Journal of Economic Perspectives. (Like all articles in JEP back to the first issue in 1987, it is freely available on-line courtesy of the American Economic Association.)

Mark Lemley offers a more detailed unpacking of the concept of "intellectual property" in a 2005 article he wrote for the Texas Law Review called "Property, Intellectual Property, and Free Riding"

Lemley writes: ""My worry is that the rhetoric of property has a clear meaning in the minds of courts,

lawyers and commentators as “things that are owned by persons,” and that fixed meaning will

make all too tempting to fall into the trap of treating intellectual property just like “other” forms

of property. Further, it is all too common to assume that because something is property, only

private and not public rights are implicated. Given the fundamental differences in the

economics of real property and intellectual property, the use of the property label is simply too

likely to mislead."

As Lemley emphasizes, intellectual property is better thought of as a kind of subsidy to encourage innovation--although the subsidy is paid in the form of higher prices by consumers rather than as tax collected from consumers and then spent by the government. A firm with a patent is able to charge more to consumers, because of the lack of competition, and thus earn higher profits. There is reasonably broad agreement among economists that it makes sense for society to subsidize innovation in certain ways, because innovators have a hard time capturing the social benefits they provide in terms of greater economic growth and a higher standard of living, so without some subsidy to innovation, it may well be underprovided.

But even if you buy that argument, there is room for considerable discussion of the most appropriate ways to subsidize innovation. How long should a patent be? Should the length or type of patent protection differ by industry? How fiercely or broadly should it be enforced by courts? In what ways might U.S. patent law be adapted based on experiences and practices in other major innovating nations like Japan or Germany? What is the role of direct government subsidies for innovation in the form of government-sponsored research and development? What about the role of indirect government subsidies for innovation in the form of tax breaks for firms that do research and development, or in the form of support for science, technology, and engineering education? Should trade secret protection be stronger, and patent protection be weaker, or vice versa?

These are all legitimate questions about the specific form and size of the subsidy that we provide to innovation. None of the questions about "intellectual property" can be answered yelling "it's my property."

The phrase "intellectual property" has been around a few hundred years, so it clearly has real staying power and widespread usage I don't expect the term to disappear. But perhaps we can can start referring to intellectual "property" in quotation marks, as a gentle reminder that an overly literal interpretation of the term would be imprudent as a basis for reasoning about economics and public policy.

Pages

▼

Friday, March 29, 2013

Thursday, March 28, 2013

Falling Labor Share of Income

I've posted on this blog in the past about how the U.S. economy has experienced a declining labor share of income. The just-released 2013 Economic Report of the President, from the Council of Economic Advisers, points out that this pattern holds across countries--and in fact is on average more severe in other developed economies than in the United States. The ERP writes (with citations omitted for readability):

"The “labor share” is the fraction of income that is paid to workers in wages, bonuses, and other compensation. ... The labor share in the United States was remarkably stable in the post-war period until the early 2000s. Since then, it has dropped 5 percentage points. .... The decline in the labor share is widespread across industries and across countries. An examination of the United States shows that the labor share has declined since 2000 in every major private industry except construction, although about half of the decline is attributable to manufacturing. Moreover, for 22 other developed economies (weighted by their GDP converted to dollars at current exchange rates), the labor share fell from 72 percent in 1980 to 60 percent in 2005."

Here's a figure showing the change.

The reasons behind the substantial fall in labor share are a "topic for future research," which is to say that there isn't an agreed-upon answer. But there is a list of possibilities from the ERP discussion:

"Proposed explanations for the declining labor share in the United States and abroad include changes in technology, increasing globalization, changes in market structure, and the declining negotiating power of labor. Changes in technology can affect the share of income going to labor by changing the nature of the labor needed for production. More specifically, much of the investment made by firms over the past two decades has been in information technology, and some economists have suggested that information technology reduces the need for traditional types of skilled labor. According to this argument, the labor share has fallen because traditional middle-skill work is being supplanted by computers, and the marginal product of labor has declined. Increasing globalization also puts pressure on wages, especially wages in the production of tradable goods that can be produced in emerging market countries and some less-developed countries. These pressures on wages can lead to reductions in the labor share. Changes in market structure and in the negotiating power of labor could also lead

to a declining labor share. One such change is the decline in unions and collective bargaining agreements in the United States."

Given that the fall in labor share of income is larger in other countries than in the U.S. economy, the cause or causes should presumably be something that had a greater effect on many other countries than on the U.S. economy. Any narrowly U.S.-centered explanations are bound to fall short in explaining an international phenomenon.

"The “labor share” is the fraction of income that is paid to workers in wages, bonuses, and other compensation. ... The labor share in the United States was remarkably stable in the post-war period until the early 2000s. Since then, it has dropped 5 percentage points. .... The decline in the labor share is widespread across industries and across countries. An examination of the United States shows that the labor share has declined since 2000 in every major private industry except construction, although about half of the decline is attributable to manufacturing. Moreover, for 22 other developed economies (weighted by their GDP converted to dollars at current exchange rates), the labor share fell from 72 percent in 1980 to 60 percent in 2005."

Here's a figure showing the change.

The reasons behind the substantial fall in labor share are a "topic for future research," which is to say that there isn't an agreed-upon answer. But there is a list of possibilities from the ERP discussion:

"Proposed explanations for the declining labor share in the United States and abroad include changes in technology, increasing globalization, changes in market structure, and the declining negotiating power of labor. Changes in technology can affect the share of income going to labor by changing the nature of the labor needed for production. More specifically, much of the investment made by firms over the past two decades has been in information technology, and some economists have suggested that information technology reduces the need for traditional types of skilled labor. According to this argument, the labor share has fallen because traditional middle-skill work is being supplanted by computers, and the marginal product of labor has declined. Increasing globalization also puts pressure on wages, especially wages in the production of tradable goods that can be produced in emerging market countries and some less-developed countries. These pressures on wages can lead to reductions in the labor share. Changes in market structure and in the negotiating power of labor could also lead

to a declining labor share. One such change is the decline in unions and collective bargaining agreements in the United States."

Given that the fall in labor share of income is larger in other countries than in the U.S. economy, the cause or causes should presumably be something that had a greater effect on many other countries than on the U.S. economy. Any narrowly U.S.-centered explanations are bound to fall short in explaining an international phenomenon.

Wednesday, March 27, 2013

Rise of the Global South

The ongoing purpose of the Human Development Report, published by the United Nations Development Programme, is to serve as a reminder that GDP isn't all that matters. Yes, income matters, but so does education, health, inequality of incomes, treatment by gender and race, voice in how you are governed, and many other dimensions. Each year, the report produces detailed tables on many measures of well-being, including a Human Development Index that ranks countries by a weighted combination of life expectancy, education, and income. he 2013 edition of the Human Development Report has the theme "The Rise of the South: Human Progress in a Diverse World." It points out that the countries of the world are seeing a convergence in HDI values: that is, the gains in low- and middle-income countries are larger than the gains in high-income countries.

Of course, the HDI is inevitably imperfect as well. The purpose of the measure is to push us all to remember the multiple dimensions of human well-being, not to pretend that human well-being can be captured in a single number. As Amartya Sen writes in some short comments accompanying the 2013 report: "Gross domestic product (GDP) is much easier to see and measure than the quality of human life that people have. But human well-being and freedom, and their connection with fairness and justice in the world, cannot be reduced simply to the measurement of GDP and its growth rate, as many people are tempted to do. The intrinsic complexity of human development is important to acknowledge ... We may, for the sake of convenience, use many simple indicators of human development, such as the HDI, based on only three variables with a very simple rule for weighting them—but the quest cannot end there. ... Assessing the quality of life is a much more complex exercise than what can be captured through only one number, no matter how judicious is the selection of variables to be included, and the choice of the procedure of weighting."

Each year, the HDR is a treasure trove of figures and tables and evidence. Here, I'll focus on one theme that caught my eye: the relationship of globalization and human development. I sometimes hear the complaint that globalization is all for the benefit of high-income countries, and is making the rest of the world worse off. But that complaint doesn't seem to hold true. As Kofi Annan said some years ago when he was Secretary-General of the United Nations, "[T]he main losers in today's very unequal world are not those who are too much exposed to globalization. They are those who have been left out."

Here's a figure illustrating the point. The horizontal axis shows the change in trade/output ratio from 1990 to 2010. The vertical axis shows "human progress" as measured by relative improvement in an HDI value. Clearly, those countries with the biggest changes in trade/output value were far more likely to have larger-than-average gains in HDI. Conversely, countries where the trade/out value dropped were far more likely to see lower-than-average gains in HDI.

Here are a comments from the HDR on our globalizing world economy:

"Over the past decades, countries across the world have been converging towards higher levels of human development, as shown by the Human Development Index (HDI), a composite measure of indicators along three dimensions:life expectancy, educational attainment and command over the resources needed for a decent living. All groups and regions have seen notable improvement in all HDI components, with faster progress in low and medium HDI countries."

Of course, the HDI is inevitably imperfect as well. The purpose of the measure is to push us all to remember the multiple dimensions of human well-being, not to pretend that human well-being can be captured in a single number. As Amartya Sen writes in some short comments accompanying the 2013 report: "Gross domestic product (GDP) is much easier to see and measure than the quality of human life that people have. But human well-being and freedom, and their connection with fairness and justice in the world, cannot be reduced simply to the measurement of GDP and its growth rate, as many people are tempted to do. The intrinsic complexity of human development is important to acknowledge ... We may, for the sake of convenience, use many simple indicators of human development, such as the HDI, based on only three variables with a very simple rule for weighting them—but the quest cannot end there. ... Assessing the quality of life is a much more complex exercise than what can be captured through only one number, no matter how judicious is the selection of variables to be included, and the choice of the procedure of weighting."

Each year, the HDR is a treasure trove of figures and tables and evidence. Here, I'll focus on one theme that caught my eye: the relationship of globalization and human development. I sometimes hear the complaint that globalization is all for the benefit of high-income countries, and is making the rest of the world worse off. But that complaint doesn't seem to hold true. As Kofi Annan said some years ago when he was Secretary-General of the United Nations, "[T]he main losers in today's very unequal world are not those who are too much exposed to globalization. They are those who have been left out."

Here's a figure illustrating the point. The horizontal axis shows the change in trade/output ratio from 1990 to 2010. The vertical axis shows "human progress" as measured by relative improvement in an HDI value. Clearly, those countries with the biggest changes in trade/output value were far more likely to have larger-than-average gains in HDI. Conversely, countries where the trade/out value dropped were far more likely to see lower-than-average gains in HDI.

Here are a comments from the HDR on our globalizing world economy:

"The South needs the North, and increasingly the North needs the South. The world is getting more connected, not less. Recent years have seen a remarkable reorientation of global production, with much more destined for international trade, which, by 2011, accounted for nearly 60% of global output. Developing countries have played a big part: between 1980 and 2010, they increased their share of world merchandise trade from 25% to 47% and their share of world output from 33% to 45%. Developing regions have also been strengthening links with each other: between 1980 and 2011, South–South trade increased from less than 8% of world merchandise trade to more than 26%. ... Global markets have played an important role in advancing progress. All newly industrializing countries have pursued a strategy of “importing what the rest of the world knows and exporting what it wants.”"Whether for a high-income country like the United States or for other countries of the world, the path to an improved standard of living for average people involves more engagement with the global economy, not less.

Tuesday, March 26, 2013

Snowbank Macroeconomics

Macroeconomic policy discussions keep reminding me,

as a Minnesotan just making it through the winter, of a car stuck in the snow. For the uninitiated, when your car is truly stuck

in a snowbank, gunning the engine doesn’t help. Your wheels spin. Maybe a

little snow flies. Maybe the car shivers in place. But you don't have traction.

Pumping the gas pedal up and down doesn't help. Twisting the steering wheel

doesn't help. Putting on your emergency blinkers is recommended--but it doesn't

get you out of the snowbank, either. Time to find a shovel, or dig that bag of

sand or cat litter out of your trunk to spread under the wheels, or look for

friendly passers-by to give you a push.

During the recession of 2007-2009 and since, U.S. policymakers have stomped hard on macroeconomic gas pedals. But although the unemployment rate has come down from its peak of 10% in October 2009, it remains near 8% --and the Congressional Budget Office is predicting sustained but still-slow growth through 2013. As a result, those who recommended stomping on the fiscal and monetary macroeconomic pedals are on the defensive. Some of them are doubling-down with the argument that if only we had stepped even harder on the macroeconomic pedals, recovery would have happened faster, and/or that we should stomp down even harder now.

My own belief is that we stepped about on fiscal and monetary gas pedals about as hard as we conceivably could back 2008 and 2009. Although I had some disagreements with the details of how some of these policies were carried out, I think these policies were generally correct at the time. But the recession ended in June 2009, according to the National Bureau of Economic Research, which is now almost four years ago. In the last few years, we have all become inured to fiscal and monetary policies that would have been viewed as extreme—even unthinkably extreme—by onlookers of all political persuasions back in 2005 or 1995 or 1985.

Consider fiscal policy first. Here's a figure generated with the ever-useful FRED website maintained by the St. Louis Fed, showing federal budget deficits and surpluses since 1960 as a share of GDP. Even with smaller budget deficits in the last couple of years, the deficits remain outsized by historical measures--in fact, larger as a share of GDP than any annual deficits since World War II.

Federal debt held by the public has grown from 40.5% of GDP in 2008 to a projected (by the Obama administration in its 2013 budget) 74.2% of GDP in 2012. This rise of 34 percentage points in the ratio of debt/GDP over four years is very large by historical standards.

For comparison, the sizable Reagan budget deficits of the 1980s increased the debt/GDP ratio from 25.8% in 1981 to 41% by 1988—a rise of about 15 percentage points over seven years. During the George W. Bush years, the debt-GDP ratio went from 32.5% in 2001 to 40.5% in 2008—a rise of 8 percentage points in eight years. Going back to the Great Depression, the debt/GDP ratio rose from 18% of GDP in 1930 to about 44% in 1940 – a rise of 26 percentage points over 10 years.

The only comparable U.S. episodes of running up this kind of debt happened during major wars. For example, the federal debt/GDP ratio went from 42.3% in 1941 to 106.2% in 1945—a rise of 54 percentage points in four years. From this perspective, the fiscal stimulus from 2008 to 2012, as measured by the rise in the debt/GDP ratio, has been about about two-thirds of the size of World War II spending. Of course, World War II, the debt/GDP ratio then fell to 80% in 1950 and 45% in 1960. Conversely, the current debt/GDP ratio is on track to keep rising.

When it comes to the very aggressive fiscal and monetary policies that the U.S. has pursued in the last few years, my own views occupy an uncomfortable middle ground. I supported those policies when they were enacted in 2008 and 2009, and continue to believe that they were mostly the right thing to do at the time. This view puts me at odds with those who opposed the policies at the time. On the other hand, I have become increasingly uncomfortable, nearly four years after the official end of the recession, with the idea that the main focus of macroeconomic policy should be to continue stomping on the macroeconomic gas pedals. This view puts me at odds with those who favor continuation or expansion of these policies. I'm reminded of an old line from Milton Friedman, "The problem with standing in the middle of the road is that you get hit by traffic going in both directions."

Snowbank macroeconomics suggests that after a financial crisis and a recession is over, and when you have tried gunning the engine for a few years, you need to think about alternatives. It's easy enough to generate a list of potential policies, many of which I've posted about over time.

It would be easy to extend this list to steps that might help to bring health care costs under control, or to take steps to address the long-run financial problems of Social Security, or implementing financial reforms to make a recurrence of the 2007-2009 disaster less likely. My point is not to limit the possibilities, but just to note that is that when macroeconomic policy is stuck in the snowbank, not working as well as anyone would like to boost growth and jobs, it's time to focus on some alternatives.

Of course, when anyone suggests that it's time to start easing back on our long-extended stomp on the macroeconomic gas pedal, and start focusing policy attention elsewhere, that person is soon accused of not believing in "standard macroeconomics," or not believing in the idea that government can help with countercylical policy in recessions. But in spring of 2013, such remonstrations are a bit like telling the driver stuck in the snowbank that if you don't favor a policy of just jamming on the gas as hard as possible for as long as possible, then you must not believe in the scientific properties of the internal combustion engine.

Sometimes aggressive expansionary macroeconomic policy can be the boost that the economy needs, and I believe that stomping on the macroeconomic gas pedal made sense in 2008 and 2009. But clearly, not all the problems faced by a sluggish economy in the aftermath of a financial crisis and deep recession have solutions as simple as mountainous budget deficits and subterranean interest rates. Indeed, the U.S. economy will eventually face some risks and tradeoffs from a continued rise in its debt/GDP ratio and in a continued policy of rock-bottom interest rates.

At a minimum, it seems fair to note that that the macroeconomic situation of 2013 is quite a bit different from the crisis and recession of 2008 and 2009, and so proposing exactly the same policies for these two different times is a little odd on its face. Moreover, the extraordinarily aggressive macroeconomic policies of the last five years have not worked in quite the ways, for better or for worse, that most people would have predicted back in 2008 or 2005 or 1995 or 1985. It seems clear that the U.S. economy needs much more than just an longer dose of the macroeconomic policies we have already been following for years.

During the recession of 2007-2009 and since, U.S. policymakers have stomped hard on macroeconomic gas pedals. But although the unemployment rate has come down from its peak of 10% in October 2009, it remains near 8% --and the Congressional Budget Office is predicting sustained but still-slow growth through 2013. As a result, those who recommended stomping on the fiscal and monetary macroeconomic pedals are on the defensive. Some of them are doubling-down with the argument that if only we had stepped even harder on the macroeconomic pedals, recovery would have happened faster, and/or that we should stomp down even harder now.

My own belief is that we stepped about on fiscal and monetary gas pedals about as hard as we conceivably could back 2008 and 2009. Although I had some disagreements with the details of how some of these policies were carried out, I think these policies were generally correct at the time. But the recession ended in June 2009, according to the National Bureau of Economic Research, which is now almost four years ago. In the last few years, we have all become inured to fiscal and monetary policies that would have been viewed as extreme—even unthinkably extreme—by onlookers of all political persuasions back in 2005 or 1995 or 1985.

Consider fiscal policy first. Here's a figure generated with the ever-useful FRED website maintained by the St. Louis Fed, showing federal budget deficits and surpluses since 1960 as a share of GDP. Even with smaller budget deficits in the last couple of years, the deficits remain outsized by historical measures--in fact, larger as a share of GDP than any annual deficits since World War II.

Federal debt held by the public has grown from 40.5% of GDP in 2008 to a projected (by the Obama administration in its 2013 budget) 74.2% of GDP in 2012. This rise of 34 percentage points in the ratio of debt/GDP over four years is very large by historical standards.

For comparison, the sizable Reagan budget deficits of the 1980s increased the debt/GDP ratio from 25.8% in 1981 to 41% by 1988—a rise of about 15 percentage points over seven years. During the George W. Bush years, the debt-GDP ratio went from 32.5% in 2001 to 40.5% in 2008—a rise of 8 percentage points in eight years. Going back to the Great Depression, the debt/GDP ratio rose from 18% of GDP in 1930 to about 44% in 1940 – a rise of 26 percentage points over 10 years.

The only comparable U.S. episodes of running up this kind of debt happened during major wars. For example, the federal debt/GDP ratio went from 42.3% in 1941 to 106.2% in 1945—a rise of 54 percentage points in four years. From this perspective, the fiscal stimulus from 2008 to 2012, as measured by the rise in the debt/GDP ratio, has been about about two-thirds of the size of World War II spending. Of course, World War II, the debt/GDP ratio then fell to 80% in 1950 and 45% in 1960. Conversely, the current debt/GDP ratio is on track to keep rising.

My guess is that most

people of would have believed, circa 2005, that a fiscal stimulus that was double

or more the size of the Reagan deficits or the Great Depression stimulus was plenty

“large enough” to deal with a recession that led to a peak unemployment rate of

10%. I have no memory of anyone back in 2008 or 2009

(myself included) who argued along these lines: "Of course, this extraordinary

fiscal stimulus may only be modestly successful. It may help drag the

economy back from the brink of catastrophe, but leave unemployment rates

high for years to come. And if or when that happens, the appropriate policy will be to continue with extraordinary and even larger deficits for five years or

more after the recession is over."

Monetary policy got the gas pedal, too. Here's a figure of the federal funds interest

rate, which up until a few years ago was the Fed's main tool for

conducting monetary policy. The Federal

Reserve took its target federal funds interest rate down to near-zero in late

2008, and has been promising to keep it near-zero into 2014. With this tool

of monetary stimulus essentially used to the maximum (there are practical difficulties in creating a negative interest rate), the Fed has taken to

policies of “quantitative easing,” which refers to direct purchases of over $2

trillion of federal debt and mortgage-backed securities, as well as policies

that seek to “twist” long-term and short-term interest rates to keep the

long-term rates low.

These monetary policies are clearly extreme steps. Looking

back at the history of the federal funds interest rate since the Federal

Reserve gained its independence from the U.S. Treasury back in 1951—and

announced that it would pursue low inflation and sustained economic growth,

rather than just keeping interest rates low so that federal borrowing costs

could also remain low--it has never tried to hold interest rates at levels this low, much less to do so for years on end.

If you had asked me (or almost anyone) back in 2005 about the likelihood of a Federal Reserve of holding the federal funds interest rate at near-zero levels for six or seven years or more, while at the same time printing money to purchase Treasury bonds and mortgage-backed securities, I would have said that the probability of such a policy was so low as to not be worth considering. I have no memory of anyone back in 2008 or 2009 (myself included) who argued along these lines: "Of course, this extraordinary monetary policy may only be modestly successful, and may well leave unemployment rates high for years to come. And if or when that happens, the appropriate policy will be to continue with near-zero interest rates for five years or more after the recession ends, along with and printing additional trillions of dollars to buy debt."

If you had asked me (or almost anyone) back in 2005 about the likelihood of a Federal Reserve of holding the federal funds interest rate at near-zero levels for six or seven years or more, while at the same time printing money to purchase Treasury bonds and mortgage-backed securities, I would have said that the probability of such a policy was so low as to not be worth considering. I have no memory of anyone back in 2008 or 2009 (myself included) who argued along these lines: "Of course, this extraordinary monetary policy may only be modestly successful, and may well leave unemployment rates high for years to come. And if or when that happens, the appropriate policy will be to continue with near-zero interest rates for five years or more after the recession ends, along with and printing additional trillions of dollars to buy debt."

When it comes to the very aggressive fiscal and monetary policies that the U.S. has pursued in the last few years, my own views occupy an uncomfortable middle ground. I supported those policies when they were enacted in 2008 and 2009, and continue to believe that they were mostly the right thing to do at the time. This view puts me at odds with those who opposed the policies at the time. On the other hand, I have become increasingly uncomfortable, nearly four years after the official end of the recession, with the idea that the main focus of macroeconomic policy should be to continue stomping on the macroeconomic gas pedals. This view puts me at odds with those who favor continuation or expansion of these policies. I'm reminded of an old line from Milton Friedman, "The problem with standing in the middle of the road is that you get hit by traffic going in both directions."

Snowbank macroeconomics suggests that after a financial crisis and a recession is over, and when you have tried gunning the engine for a few years, you need to think about alternatives. It's easy enough to generate a list of potential policies, many of which I've posted about over time.

- A tax reform agenda would involve reducing tax deductions, exemptions and credits, and using the revenue for a combination of lower marginal tax rates and deficit reduction.

- A globalization agenda might focus on how the federal government can facilitate stronger ties from the U.S. economy to the emerging economies of the world, where most of global economic growth will be happening in the decades ahead. Trade agreements are part of the picture, but more broadly, policies would include improving communications, transportation infrastructure, cross-border processes for goods and people, language training, aligning legal systems, and more.

- An energy policy agenda might follow my preference for a "Drill Baby Carbon Tax," which would be a policy that both encouraged the development of unconventional energy resources with all deliberate speed while also imposing a carbon tax to provide incentives for reduced emissions.

- An education and training agenda might look seriously into two issues: how to facilitate the development of education and career paths for those who aren't going to complete a four-year college degree, like apprenticeships, and also how to boost K-12 achievement through mixtures of institutional reforms and incentives.

- An innovation agenda might look at spending on research and development, at reform of the patent system, at science and technology education, and at simplifying the regulatory burden on those who who want to start a business.

- An infrastructure agenda shouldn't just involve pouring concrete, but would go beyond transportation to look also at communications and energy infrastructure. It would also look at smart use of infrastructure, like how to set prices for electricity in a way that encourages shifting demand to lower-use times, or how to set prices that could reduce congestion of roads and airports, or how to harden communications and information technology infrastructure against cyberattacks.

- A underwater mortgage agenda would look at how to reduce the burden the debt burden for more homeowners more quickly.

It would be easy to extend this list to steps that might help to bring health care costs under control, or to take steps to address the long-run financial problems of Social Security, or implementing financial reforms to make a recurrence of the 2007-2009 disaster less likely. My point is not to limit the possibilities, but just to note that is that when macroeconomic policy is stuck in the snowbank, not working as well as anyone would like to boost growth and jobs, it's time to focus on some alternatives.

Of course, when anyone suggests that it's time to start easing back on our long-extended stomp on the macroeconomic gas pedal, and start focusing policy attention elsewhere, that person is soon accused of not believing in "standard macroeconomics," or not believing in the idea that government can help with countercylical policy in recessions. But in spring of 2013, such remonstrations are a bit like telling the driver stuck in the snowbank that if you don't favor a policy of just jamming on the gas as hard as possible for as long as possible, then you must not believe in the scientific properties of the internal combustion engine.

Sometimes aggressive expansionary macroeconomic policy can be the boost that the economy needs, and I believe that stomping on the macroeconomic gas pedal made sense in 2008 and 2009. But clearly, not all the problems faced by a sluggish economy in the aftermath of a financial crisis and deep recession have solutions as simple as mountainous budget deficits and subterranean interest rates. Indeed, the U.S. economy will eventually face some risks and tradeoffs from a continued rise in its debt/GDP ratio and in a continued policy of rock-bottom interest rates.

At a minimum, it seems fair to note that that the macroeconomic situation of 2013 is quite a bit different from the crisis and recession of 2008 and 2009, and so proposing exactly the same policies for these two different times is a little odd on its face. Moreover, the extraordinarily aggressive macroeconomic policies of the last five years have not worked in quite the ways, for better or for worse, that most people would have predicted back in 2008 or 2005 or 1995 or 1985. It seems clear that the U.S. economy needs much more than just an longer dose of the macroeconomic policies we have already been following for years.

Monday, March 25, 2013

Low-Income, High-Achieving Students

Consider the situation of high-achieving students from low-income families. In some ways, what happens to them has a disproportionate effect on the degree of economic and social mobility in U.S. society. One would expect a disproportionate share of this group to show upward mobility. But at least in college choices, many of them are heading for nonselective schools that seem below their ability level. Caroline M. Hoxby and Christopher Avery present the evidence in "The Hidden Supply of High-Achieving, Low-Income Students." The conference paper was presented last week at the Spring 2013 Conference on the Brookings Papers on Economic Activity; Brookings also put out put a readable summary of "Key Findings" with some infographics.

Hoxby and Avery define the group of interest here as students from families with annual income less than $41,472 (the bottom quarter of households), SAT scores in the top 10% of the distribution of those taking the test (which is about 40% of high school graduates), and high school grade point average of A- or higher. They have data from the SAT folks on where students apply, based on where they have their SAT scores sent. If the student's test score is close to the median SAT score of those attending, they call it a "match." Students might also "reach" for a school where the median SAT score is above their own, or look for a "safety school" where the median test score is below their own. But the striking result is that so many high-achieving students from low-income families tend to apply to non-selective schools.

The top figure shows application patterns for high-achieving students from high-income (top quarter of income distribution) families, while the figure beneath it shows application patterns for high-achieving students from low-income families.

Hoxby and Avery write: "[W]e show that a large number--probably the vast majority--of very high-achieving students from low-income families do not apply to a selective college or university. This is in contrast to students with the same test scores and grades who come from high-income backgrounds: they are overwhelmingly likely to apply to a college whose median student has achievement much like their own. This gap is puzzling because the subset of high-achieving, low-income students who do apply to selective institutions are just as likely to enroll and progress toward a degree at the same pace as high-income students with equivalent test scores and grades. Added to the puzzle is the fact that very selective institutions not only offer students much richer instructional, extracurricular, and other resources, they also offer high-achieving, low-income students so much financial aid that the students would often pay less to attend a selective institution than the far less selective or non-selective post-secondary institutions that most of them do attend."

Hoxby and Avery define the group of interest here as students from families with annual income less than $41,472 (the bottom quarter of households), SAT scores in the top 10% of the distribution of those taking the test (which is about 40% of high school graduates), and high school grade point average of A- or higher. They have data from the SAT folks on where students apply, based on where they have their SAT scores sent. If the student's test score is close to the median SAT score of those attending, they call it a "match." Students might also "reach" for a school where the median SAT score is above their own, or look for a "safety school" where the median test score is below their own. But the striking result is that so many high-achieving students from low-income families tend to apply to non-selective schools.

The top figure shows application patterns for high-achieving students from high-income (top quarter of income distribution) families, while the figure beneath it shows application patterns for high-achieving students from low-income families.

Hoxby and Avery write: "[W]e show that a large number--probably the vast majority--of very high-achieving students from low-income families do not apply to a selective college or university. This is in contrast to students with the same test scores and grades who come from high-income backgrounds: they are overwhelmingly likely to apply to a college whose median student has achievement much like their own. This gap is puzzling because the subset of high-achieving, low-income students who do apply to selective institutions are just as likely to enroll and progress toward a degree at the same pace as high-income students with equivalent test scores and grades. Added to the puzzle is the fact that very selective institutions not only offer students much richer instructional, extracurricular, and other resources, they also offer high-achieving, low-income students so much financial aid that the students would often pay less to attend a selective institution than the far less selective or non-selective post-secondary institutions that most of them do attend."

To illustrate this point about affordability, Hoxby and Avery calculate the cost with financial aide for a student with a family at the 20th percentile of the income distribution to attend various more-selective and less-selective schools.

So it isn't not a matter of out-of-pocket cost, what makes a high-achieving student from a low-income family more likely to attend a selective college? Although the answer to this question is still being sorted out, Hoxby and Avery offer some descriptive evidence that the answer lies in the networks between high schools and colleges. Most of the high-achieving, low-income students who apply to selective schools live in urban areas, where a number of such college are nearby. They are also more likely to have attended magnet high schools where a relatively larger "critical mass" of other students are also looking at selective colleges.

Almost all selective colleges do reach out to high-achieving low-income students, but these outreach efforts tend to focus on particular schools in their own geographic area. Hoxby and Avery write: "In

fact, we know from colleges' own published materials and communications with the authors that many colleges already make great efforts to seek out low-income students from their area. These

strategies, while no doubt successful in their way, fall somewhat under the heading of "searching

under the lamp-post." That is, many colleges look for low-income students where the college is instead of looking for low-income students where the students are." But how colleges can reach out to high-achieving, low-income students at other places, in a targeted way that doesn't involve having their efforts get lost in the snowstorm of college brochures, is a difficult question.

Friday, March 22, 2013

Retire Now, Social Security Later

Most people start drawing Social Security benefits as soon as they retire. But as John B. Shoven explains in "Efficient Retirement Design," a March 2013 Policy Brief for the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research, this strategy is usually a mistake--and a mistake that have a loss in value of as much as $250,000. To understand the issues here, let's set the stage with some facts.

Most people have two major assets at retirement: Social Security and a retirement account like an IRA or 401k, where they have some choice about when and how to draw down that account. Most people follow a strategy where they draw on Social Security right when they retire. Shoven writes: "Figure 1 shows the distribution of the months of delay between when someone retires (or when they become 62 if they retired before that age) and when they start their Social Security benefits. What you are supposed to see in Figure 1 is that the vast majority of people start their Social Security almost immediately upon reaching 62 or retiring.... Figure 1 makes it look like people think that starting Social Security and retiring are one and the same thing."

To understand the theme here, it's useful to think of Social Security as a kind of annuity--that is, an investment that pays out some amount as long as you live. But Social Security is a special kind of annuity. If you delay receiving Social Security, your annual benefits are adjusted upward each year that you wait. In addition, Social Security payments are adjusted upward for increases in the cost of living each year. It's difficult and costly to take your own personal retirement benefits and try to buy that kind of inflation-adjusted private-sector annuity with these properties. With life expectancies getting longer and today's climate of very low interest rates, buying a Social Security-style annuity is increasingly valuable.

For most people, your standard of living after retirement will be higher if you spend the first few years after retirement living on your years on your discretionary retirement funds, and defer Social Security to get the higher benefits later. In effect, by using discretionary funds early in retirement, you are using those funds to "buy" a later date for starting Social Security benefits, which raises the value of that Social Security annuity.

Shoven demonstrates this point with a wide variety of examples, and in a working paper written with Sita Slavov, they consider even more examples and issues. As one example, Shoven suggests looking at a married couple, both age 62, who want to retire. The husband's average earnings have been $56,000 per year, while the wife's average earnings have been $42,000 per year. They have $257,000 in their retirement accounts. One possibility is that they both start drawing Social Security immediately. However, in another alternative they instead live on their retirement account until age 66, when the lower earner starts drawing Social Security, and then at 70, the higher earner starts drawing Social Security. The husband's monthly Social Security check at age 70 will be 76 percent higher than if he had started drawing benefits at age 62.

This "66/70 strategy," in which the lower earner of a couple doesn't draw Social Security benefits until age 66 and the higher earner defers benefits until age 70, is often a useful approach. In this example, the couple ends up with $600 more in income per month at age 70. The gain gets bigger over time, as Social Security benefits are adjusted upward. For example, if inflation is 2% per year, and the couple lives to age 90, their income would be $1400/month higher because of following the 66/70 choice for drawing Social Security benefits, instead of drawing the benefits when they retired at age 62. The gain over their lifetime from drawing benefits later is more than $200,000.

Shoven concludes: "The general message, however, is that Social Security deferral is a good deal for most people. Wehave looked at people with far less in terms of assets than the couple just described. We have looked at the matter by race, by education and by health. ...Our conclusion is that most people should be using at least a substantial part of their retirement savings to defer Social Security rather than supplement it. Almost no one is getting it right."

The question of why people don't delay Social Security benefits hasn't been much researched, but it's fun to speculate. For some people, presumably the answer is just that they haven't considered deferring Social Security for a few years after retirement. Some people might fear that Social Security won't be there in the future. Others might be concerned that if they don't take Social Security immediately, they might die before receiving it (although in this case, death would seem to be a bigger problem than leaving some government benefits unclaimed!). Not taking Social Security immediately upon retirement feels like "leaving money on the table." Spending your discretionary money first feels as you are giving up your flexibility and your cushion. But although these kinds of feelings are real, they don't change the arithmetic of the situation, which shows that spending discretionary retirement income first and drawing Social Security later will provide gains to most people.

Most people have two major assets at retirement: Social Security and a retirement account like an IRA or 401k, where they have some choice about when and how to draw down that account. Most people follow a strategy where they draw on Social Security right when they retire. Shoven writes: "Figure 1 shows the distribution of the months of delay between when someone retires (or when they become 62 if they retired before that age) and when they start their Social Security benefits. What you are supposed to see in Figure 1 is that the vast majority of people start their Social Security almost immediately upon reaching 62 or retiring.... Figure 1 makes it look like people think that starting Social Security and retiring are one and the same thing."

To understand the theme here, it's useful to think of Social Security as a kind of annuity--that is, an investment that pays out some amount as long as you live. But Social Security is a special kind of annuity. If you delay receiving Social Security, your annual benefits are adjusted upward each year that you wait. In addition, Social Security payments are adjusted upward for increases in the cost of living each year. It's difficult and costly to take your own personal retirement benefits and try to buy that kind of inflation-adjusted private-sector annuity with these properties. With life expectancies getting longer and today's climate of very low interest rates, buying a Social Security-style annuity is increasingly valuable.

For most people, your standard of living after retirement will be higher if you spend the first few years after retirement living on your years on your discretionary retirement funds, and defer Social Security to get the higher benefits later. In effect, by using discretionary funds early in retirement, you are using those funds to "buy" a later date for starting Social Security benefits, which raises the value of that Social Security annuity.

Shoven demonstrates this point with a wide variety of examples, and in a working paper written with Sita Slavov, they consider even more examples and issues. As one example, Shoven suggests looking at a married couple, both age 62, who want to retire. The husband's average earnings have been $56,000 per year, while the wife's average earnings have been $42,000 per year. They have $257,000 in their retirement accounts. One possibility is that they both start drawing Social Security immediately. However, in another alternative they instead live on their retirement account until age 66, when the lower earner starts drawing Social Security, and then at 70, the higher earner starts drawing Social Security. The husband's monthly Social Security check at age 70 will be 76 percent higher than if he had started drawing benefits at age 62.

This "66/70 strategy," in which the lower earner of a couple doesn't draw Social Security benefits until age 66 and the higher earner defers benefits until age 70, is often a useful approach. In this example, the couple ends up with $600 more in income per month at age 70. The gain gets bigger over time, as Social Security benefits are adjusted upward. For example, if inflation is 2% per year, and the couple lives to age 90, their income would be $1400/month higher because of following the 66/70 choice for drawing Social Security benefits, instead of drawing the benefits when they retired at age 62. The gain over their lifetime from drawing benefits later is more than $200,000.

Shoven concludes: "The general message, however, is that Social Security deferral is a good deal for most people. Wehave looked at people with far less in terms of assets than the couple just described. We have looked at the matter by race, by education and by health. ...Our conclusion is that most people should be using at least a substantial part of their retirement savings to defer Social Security rather than supplement it. Almost no one is getting it right."

The question of why people don't delay Social Security benefits hasn't been much researched, but it's fun to speculate. For some people, presumably the answer is just that they haven't considered deferring Social Security for a few years after retirement. Some people might fear that Social Security won't be there in the future. Others might be concerned that if they don't take Social Security immediately, they might die before receiving it (although in this case, death would seem to be a bigger problem than leaving some government benefits unclaimed!). Not taking Social Security immediately upon retirement feels like "leaving money on the table." Spending your discretionary money first feels as you are giving up your flexibility and your cushion. But although these kinds of feelings are real, they don't change the arithmetic of the situation, which shows that spending discretionary retirement income first and drawing Social Security later will provide gains to most people.

Thursday, March 21, 2013

Automatic Fiscal Stabilizers

Standard macroeconomic theory suggests that a central government can ameliorate swings in the business cycle through fiscal policy. Thus, when an economy is in recession, it's a good time for the government to prop up demand with some combination of tax cuts or spending increases. Conversely, when an economy is running red-hot, it's a good time for the government to slow down demand with some combination of tax increases or spending cuts. Indeed, a number of tax and spending programs adjust this way automatically, without the passage of legislation, and thus are know as "automatic stabilizers." The Congressional Budget Office has published a short primer: "The Effects of Automatic Stabilizers on the Federal Budget as of 2013."

For example, during the sluggish aftermath of the Great Recession, more people are drawing unemployment benefits, and relying on programs like Food Stamps and Medicaid. Conversely, the unemployed and underemployed are making lower income tax payments than they would have made if employed. These effects are built into the design of the tax code and into the design of safety net programs. This is how automatic stabilizers work. The CBO reports: "In fiscal year 2012, CBO estimates, automatic stabilizers added $386 billion to the federal budget deficit, an amount equal to 2.3 percent of potential GDP ... That outcome marked the fourth consecutive year that automatic stabilizers added to the deficit by an amount equal to or exceeding 2.0 percent of potential GDP, an impact that had previously been equaled or exceeded only twice in the past 50 years, in fiscal years 1982 and 1983 ..."

Here's a figure showing the actual budget deficits with the automatic stabilizers, and then what the budget deficit would have looked like in the absence of automatic stabilizers. Notice that during the dot-com boom years of the late 1990s, the actual budget surplus was larger than it would have been without the automatic stabilizers--that is, the stabilizers were working to slow down the economy. Around 2005, the automatic stabilizers were neither making the actual budget deficit higher or lower. But then during the recent recession, as in past recessions, the automatic stabilizers contribute to making the deficit larger.

For the record, you may sometimes hear someone make a comment about the “cyclically adjusted deficit” or the “structural deficit.” These terms refer to what the budget deficit (or surplus) would be without the automatic stabilizers--it's the blue line in the figure above.

As a policy tool, automatic fiscal stabilizers have the great advantage that they take effect in real time as the economy changes, without a need for legislation. Even those who may oppose discretionary fiscal policy, where additional tax cuts or spending increases are passed after a recession is underway, don't oppose the idea that when people's income falls, their taxes should fall and their use of safety net programs should rise.

For example, during the sluggish aftermath of the Great Recession, more people are drawing unemployment benefits, and relying on programs like Food Stamps and Medicaid. Conversely, the unemployed and underemployed are making lower income tax payments than they would have made if employed. These effects are built into the design of the tax code and into the design of safety net programs. This is how automatic stabilizers work. The CBO reports: "In fiscal year 2012, CBO estimates, automatic stabilizers added $386 billion to the federal budget deficit, an amount equal to 2.3 percent of potential GDP ... That outcome marked the fourth consecutive year that automatic stabilizers added to the deficit by an amount equal to or exceeding 2.0 percent of potential GDP, an impact that had previously been equaled or exceeded only twice in the past 50 years, in fiscal years 1982 and 1983 ..."

Here's a figure showing the actual budget deficits with the automatic stabilizers, and then what the budget deficit would have looked like in the absence of automatic stabilizers. Notice that during the dot-com boom years of the late 1990s, the actual budget surplus was larger than it would have been without the automatic stabilizers--that is, the stabilizers were working to slow down the economy. Around 2005, the automatic stabilizers were neither making the actual budget deficit higher or lower. But then during the recent recession, as in past recessions, the automatic stabilizers contribute to making the deficit larger.

For the record, you may sometimes hear someone make a comment about the “cyclically adjusted deficit” or the “structural deficit.” These terms refer to what the budget deficit (or surplus) would be without the automatic stabilizers--it's the blue line in the figure above.

As a policy tool, automatic fiscal stabilizers have the great advantage that they take effect in real time as the economy changes, without a need for legislation. Even those who may oppose discretionary fiscal policy, where additional tax cuts or spending increases are passed after a recession is underway, don't oppose the idea that when people's income falls, their taxes should fall and their use of safety net programs should rise.

Wednesday, March 20, 2013

The Home Bias Puzzle

Most people are familiar with the benefits of diversification of their investments. "Don't put all your eggs in one basket!" But in one particular way, most investors seem dramatically underdiversified in this globalizing economy: that is, they have a disproportionate share of their investments in their own country, rather than diversified across the countries of the world. In the most recent issue of the Journal of Economic Literature, Nicolas Coeurdacier and Hélène Rey discuss what is known about "Home Bias in Open Economy Financial Macroeconomics." The JEL is not freely available on-line, but many academics will have access either through library subscriptions or through their membership in the American Economic Association.

As as starting point, consider this table. The first column is a list of countries. The second column shows what share of the total global market for equities is represented by the domestic market in that country. Thus, the Australian stock market by value is 1.8% of the value of all global stock markets. The U.S. stock market by value is 32.6% of the value of all global stock markets. The second column shows the share of investments by people in each country that are in the stocks of their own country. Thus, Australia's stock market is 1.8% of the world total, but people in Australia have 76.1% of their equity investments in the Australian stock market. This is home bias in action.

The third column of the table is a common measure of "equity home bias" or EHB, defined as:

The third column of the table is a common measure of "equity home bias" or EHB, defined as:

Home bias has been declining over the last few decades in most high-income countries, and some low-income countries, but it remains high. Here are some illustrative figures for home bias in equities, bonds, and bank assets.

But despite the declines in home bias, it remains notably high. Why are people around the world not taking better advantage of the opportunities for global diversification? This puzzle hasn't been fully resolved, but Coeurdacier and Rey discuss the answers that have been proposed. For example:

As as starting point, consider this table. The first column is a list of countries. The second column shows what share of the total global market for equities is represented by the domestic market in that country. Thus, the Australian stock market by value is 1.8% of the value of all global stock markets. The U.S. stock market by value is 32.6% of the value of all global stock markets. The second column shows the share of investments by people in each country that are in the stocks of their own country. Thus, Australia's stock market is 1.8% of the world total, but people in Australia have 76.1% of their equity investments in the Australian stock market. This is home bias in action.

The third column of the table is a common measure of "equity home bias" or EHB, defined as:

The third column of the table is a common measure of "equity home bias" or EHB, defined as:Home bias has been declining over the last few decades in most high-income countries, and some low-income countries, but it remains high. Here are some illustrative figures for home bias in equities, bonds, and bank assets.

But despite the declines in home bias, it remains notably high. Why are people around the world not taking better advantage of the opportunities for global diversification? This puzzle hasn't been fully resolved, but Coeurdacier and Rey discuss the answers that have been proposed. For example:

- People must weigh the benefits of global diversification against the risk of being exposed to fluctuations in exchange rates, and they may not have an easy way to protect themselves against those fluctuations.

- Some people have wage income where they are already somewhat exposed to economic fluctuations in other countries, while other people do not--which will affect how much diversification they can achieve by investing in other countries.

- Many domestic firms already have significant exposure to international markets, and so investing in those firms means that people are more exposed to economic factors in other countries than it might at first appear.

- Benefits of global diversification need to be weighed against the transactions costs of making such investments, which include differences in tax treatments between national and foreign assets or differences in legal frameworks. Some countries have regulations that make the transactions costs of foreign investment deliberately higher.

- Many investors have better information on investments in their own country than on investments in other countries, so the perceive the foreign investments as being riskier.

- Many investors have certain "behavioral" biases like overconfidence or focusing on what is familiar that tend to drive them toward toward investing in home assets, rather than foreign ones.

Tuesday, March 19, 2013

Perspectives on a Sluggish Recovery

The 2013 edition of the Economic Report of the President, written annually by the President's Council of Economic, is now available. I'll probably do several posts about various themes and topics from the report during the next week or so. Here, I want to focus on some perspectives that the report offers about the sluggish economic recovery.

One intriguing insight, at least for me, is that the pace of the recovery of the economy from the end of the recession has in some ways actually been not too far from historical patterns. However, this recession was exceptionally long and deep, which helps to explain why the recovery feels so inadequate. For example, here's a figure showing the pattern of employment after recession. On the horizontal axis, the date of 0 is the "trough" or final month of the recession. That level of employment is set equal to an index number of 100 on the vertical axis. Notice that after the trough of the recession, the growth in jobs has been similar to aftermath of the 1991 recession and faster than the 2001 recession. However, if you look at the time before the recession, the fall in jobs during the recession, before the trough, was much longer and much deeper in the Great Recession.

But there are some other ways of looking at this slower growth, as well. For example, compare the U.S. recovery to that of the economy of the countries of Europe that are in the euro area, or the economy of the United Kingdom. The pattern looks similar in 2007, leading up to the recession, and through 2008 and into 2009, when the recession hit. The recovery for the euro area also looked farly similar to the U.S. experience for a time, up to early 2011. At about that time, the euro area economy began to suffer through its own second wave of problems. Thus, while real GDP in the U.S. economy had exceeded pre-recession levels by late 2011, real GDP in the euro area and the UK has not yet recovered to pre-recession levels. The U.S. recovery has been sluggish; for the euro area, the recovery is not yet complete.

The report also points out that there is an historical pattern that periods of economic recovery have been experiencing slower growth with each business cycle since 1960. Consider the figure below, showing real GDP from 1960 to 2012. Each of the dashed lines is an extrapolation from the period of economic growth before a recession hit. The slopes of those dashed lines are getting flatter over time, showing that the growth phase of each business cycle has been slowing down.

There are two broad reasons for this slowdown. Real GDP growth is in part due to population growth: more population has meant more workers and faster growth, but population growth has been declining over time, reducing the rate of GDP growth. The other factor is that productivity levels have sagged since the 1960s. There was a modest resurgence of productivity growth for a time in the second half of the 1990s and into the early 2000s, but that boost seems to have faded.

One of my ongoing mental tasks during the past few years and the next few years is to organize my thoughts about the patterns of the Great Recession and its aftermath, and to put those patterns in historical and international context.

One intriguing insight, at least for me, is that the pace of the recovery of the economy from the end of the recession has in some ways actually been not too far from historical patterns. However, this recession was exceptionally long and deep, which helps to explain why the recovery feels so inadequate. For example, here's a figure showing the pattern of employment after recession. On the horizontal axis, the date of 0 is the "trough" or final month of the recession. That level of employment is set equal to an index number of 100 on the vertical axis. Notice that after the trough of the recession, the growth in jobs has been similar to aftermath of the 1991 recession and faster than the 2001 recession. However, if you look at the time before the recession, the fall in jobs during the recession, before the trough, was much longer and much deeper in the Great Recession.

The pace of economic growth in the recovery has been notably slower than historical averages. For example, here's a figure comparing growth after the trough since the two previous recessions of 2001 and 1991, as well as against the average period for all the recessions from 1960 to 2007. The current recovery clearly lags behind.

The report also points out that there is an historical pattern that periods of economic recovery have been experiencing slower growth with each business cycle since 1960. Consider the figure below, showing real GDP from 1960 to 2012. Each of the dashed lines is an extrapolation from the period of economic growth before a recession hit. The slopes of those dashed lines are getting flatter over time, showing that the growth phase of each business cycle has been slowing down.

There are two broad reasons for this slowdown. Real GDP growth is in part due to population growth: more population has meant more workers and faster growth, but population growth has been declining over time, reducing the rate of GDP growth. The other factor is that productivity levels have sagged since the 1960s. There was a modest resurgence of productivity growth for a time in the second half of the 1990s and into the early 2000s, but that boost seems to have faded.

One of my ongoing mental tasks during the past few years and the next few years is to organize my thoughts about the patterns of the Great Recession and its aftermath, and to put those patterns in historical and international context.

Monday, March 18, 2013

The Decline in Private K-12 Enrollment

Enrollment in private K-12 schools has been falling in recent years, and private schools are a much smaller share of K-12 enrollment than a half-century ago. Stephanie Ewert of the Social, Economic, and Housing Statistics Division of the U.S. Census Bureau lays out some facts in "The Decline in Private School Enrollment," published in January 2013 as SEHSD Working Paper Number FY12-117.

Here's a figure showing the long-term decline in private share of total K-12 school enrollment. Notice that the big decline happened in the 1960s, but there is also a decline since the early 2000s.

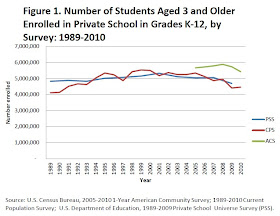

And here's a figure showing the number of students enrolled in private schools since 1989. The Current Population Survey and Private School Universe Survey have data over this time, and both show a rise in private school enrollments in the 1990s, but a fall since around roughly 2000.

Ewert focuses on presenting facts and suggestions possible hypotheses, mostly leaving the airier speculation to the rest of us. So here goes.

The very large drop in the importance of private schools back in the 1960s was surely intertwined with two big factors. One was that as the baby boom generation entered school age, they were clearly much more likely to attend public schools than their predecessors. The other factor was the changing importance of the Catholic school system. As Ewert points out, Catholic schools made up 60 percent of private school enrollment in 1930, and in large cities like New York City, Catholic schools educated one-third of all students at that time. But the move of the population to schools in the suburbs largely left the Catholic schools behind, and one suspects that something about the ethos of the 1960s made the Catholic schools a less attractive alternative for many families who would have considered them in the 1950s and earlier.

The more recent drop doesn't look as large in long-term perspective, but it's still significant. Ewert writes: "For example, the PSS shows that there were 5.3 million students enrolled in private school in the 2001-2002 school year but only 4.7 million in the 2009-2010 school year. Similarly, the CPS data indicate that there were 5.4 million private school students in 2002 but only 4.5 million in 2010."

Likely explanations for this more recent decline would include: the rise of "charter" public schools, the rise of homeschooling, the reputation problems of the Catholic church in the aftermath of its child abuse scandals, and in the last few years the economic woes that have made paying private school tuition harder for many families.

I attended public schools from K-12, and I have little sentimentality about private ones. But I do think that K-12 education needs to evolve with the times, and that evolution is usually built on seeing how different approaches work, and that public schools have not always been much good at experimenting with different approaches and seeing what works for different student groups. Private schools have long offered a range of alternatives, and if they continue to face, I hope that some mixture of charter schools and home schooling can continue to offer a source for experimentation in education.

Friday, March 15, 2013

Electric vs. Conventional Cars on Conservation

Earlier this week, Bjorn Lomborg wrote an intriguing op-ed for the Wall Street Journal titled "Green Cars Have a Dirty Little Secret: Producing and charging electric cars means heavy carbon-dioxide emissions." I always enjoy reading Lomborg, but I'm also the sort of person who prefers to read the research myself. The underlying article is "Comparative Environmental Life Cycle Assessment of Conventional and Electric Vehicles," by Troy R. Hawkins, Bhawna Singh, Guillaume Majeau-Bettez, and Anders Hammer Strømman. It appears in the February 2013 issue of the Journal of Industrial Ecology (17: 1, pp. 53-64).

The authors point out in acronym-heavy style that comparing the environmental costs of electric vehicles (EVs) with internal combustion engine vehicles (ICEVs), it's important to do a life cycle assessment (LCA) that considers all aspects of producing the car, using the car, and the energy sources that propel the car, so as to take account of global warming potential (GWP) and other environmental costs. To make this more concrete, the comparison is between a car similar to a Nissan Leaf electric vehicle with a car similar to a conventional engine Mercedes A-series, which are comparable cars in size and power. Under certain conditions, electric cars are more environmentally friendly than conventional engines, but that conclusion holds only under certain conditions.

Source of electricity. If the electricity for the electric car is generated by wind power or hydroelectic power, then no carbon is emitted in producing that electricity. But if the electricity is generated by burning coal, carbon and a number of other pollutants are created. While electric cars reduce tailpipe emissions, it may be with a tradeoff of increasing emissions elsewhere. In addition, if the internal combustion engine is a diesel, it will run relatively clean. Thus, they write:

Number of miles the car is driven. Producing the large and powerful batteries needed for electric cars has environmental costs. By the calculations of this group, in a conventional car about 10% of the effect on climate change happens in production, and the rest in the use of the car over its lifetime. But for an electric car, about 50% of the effect on climate change happens in production, with the rest occurring over its lifetime (depending on the underlying source of the electricity used). As a result, the number of miles that a car is driven over its lifetime ends up making a big difference in its environmental effect. They write:

But here's a coda from their analysis that struck me as interesting. Say for the sake of argument that a main effect of moving to electric cars was just to shift pollution to the factories that make batteries and to the facilities for generating electricity. It may be easier for society to set up incentives and programs for reducing pollution at a relatively few fixed big sites, rather than dealing with pollution from millions of tailpipes.

For some other recent examples of choices and tradeoffs that I've discussed on this blog, see:

Source of electricity. If the electricity for the electric car is generated by wind power or hydroelectic power, then no carbon is emitted in producing that electricity. But if the electricity is generated by burning coal, carbon and a number of other pollutants are created. While electric cars reduce tailpipe emissions, it may be with a tradeoff of increasing emissions elsewhere. In addition, if the internal combustion engine is a diesel, it will run relatively clean. Thus, they write:

"When powered by average European electricity, EVs [electric vehicles) are found to reduce GWP [global warming potential] by 20% to 24% compared to gasoline ICEVs [internal combustion engine vehicles] and by 10% to 14% relative to diesel ICEVs under the base case assumption of a 150,000 km vehicle lifetime. When powered by electricity from natural gas, we estimate LiNCM [lithium-ion battery] EVs offer a reduction in GHG [greenhouse gas] emissions of 12% compared to gasoline ICEVs, and break even with diesel ICEVs. EVs powered by coal electricity are expected to cause an increase in GWP of 17% to 27% compared with diesel and gasoline ICEVs."