Back in 2011, the Harvard Business School launched what it called th US Competitiveness Project. The 2016 report, authored by Michael E. Porter, Jan W. Rivkin, Mihir A. Desai, and Manjari Ramanis, is called Problems Unsolved and a Nation Divided: The State of U.S. Competitiveness 2016.

For the record, the term "competitiveness" can be controversial in a lot of policy discussions, because while being more "competitive" seems like it should be a good thing, the ways in which you are competitive matter. After all, the US would be in some sense more "competitive" in global markets if US wages were lower, but that wouldn't be a desirable policy. The report offers this definition: " A nation is competitive if it creates the conditions where two things occur simultaneously: businesses operating in the nation can (1) compete successfully in domestic and international markets, while (2) maintaining and improving the wages and living standards of the average citizen. When these occur together, a nation prospers. When one occurs without the other, a nation is not truly competitive

and prosperity is not sustainable. If business succeeds but the average worker is losing ground, or when worker incomes rise but businesses can no longer compete, the nation is not competitive. A hallmark of a competitive economy, then, is prosperity that is widely shared."

Some of the discussion in the report is an overview of themes that will be familiar to readers of this blog: how US productivity growth has slowed, labor force participation has fallen, and the like. There are also survey result from HBS alumni about how they see the economy and the policy environment. Here, I'll make no effort to review the report as a whole and I'll ignore the opinions of HBS alumni, but instead will just point to some facts and figures that jumped out at me.

For example, this figure divides up total US jobs into those in industries which compete in international markets (like machinery and IT equipment), and industries which are "local" in the sense that they face relatively little international competition (like health care and business services). Two facts emerge. One is that the total number of US jobs in internationally competitive sectors has been essentially flat at about 40 million since 1990, while all the growth in US jobs in the last 25 years is due to the "local" industries. The other fact is that the jobs in internationally competitive industries tend to pay a lot higher wages.

The report offers some figures showing the decline in "labor force participation," which refers to the share of the population that is either employer or unemployed--but leaves out those who are detached from the labor force and neither working nor looking for work. Given the different workforce patterns of men and women in recent decades, it's conventional to separate labor force participation rates by gender. This figure shows "cohorts," which refers to the share of "prime-age" US men working at different ages. For example, the top line shows for the cohort of men born from 1933-1942, labor force participation was near 98% at age 30, before declining to 86% by age 54. However, for each cohort of men born since then, the labor force participation rate has dropped. For those born from 1983-1992, for example, about 90% were in the labor force at age 30.

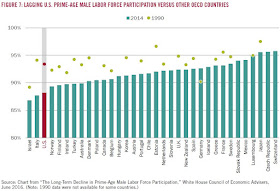

This decline in labor force participation is an international phenomenon, but it is especially pronounced in the US. In this figure, the circles show labor force participation in 1990, while the bars show labor force participation in 2014. The US is shown in red.

Small businesses are also playing a lesser role in the US economy. The share of all US businesses that is less than 5 years old has been dropping over time, going back several decades.

In addition, the share of jobs being generated by small businesses is dropping. The figure shows that the total number of jobs at firms with 1-9 employees, or with 10-99 employees, is about the same now as it was back in the late 1990s. US job growth since the late 1990s is all at larger firms.

One final snapshot is to point out that the household distribution of income has large stagnated for the last 15 years or so. As I've argued in the past (for example, here and here), the big surge of rising inequality was a 1980s and 1990s phenomenon.

Wisely, the report doesn't try to dig very deeply into these patterns of slow economic growth, effects of a globalizing economy, labor force participation, small business, and incomes that are stagnating at a much more unequal level than several decades ago. It just puts the topics on the table for discussion.