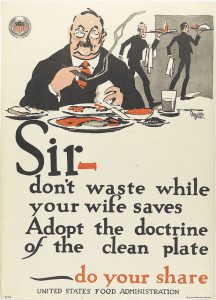

And here's another:

Although that first Clean Plate Club officially ended with World War I, the idea seems to have popped up again over the years, during the Great Depression, during World War II, and at numerous family dinner tables all around the United States ever since.

The latest version is courtesy of the National Resources Defense Council and its "Save the Food" project. In radio ads and billboard spots, along with the website, the NDRC often makes a claim: "A 4-person family loses $1500 a year on wasted food." Or as NDRC puts it in a 2017 report: "In 2012, NRDC published a groundbreaking report that revealed that up to 40 percent of food in the United States goes uneaten. That is on average 400 pounds of food per person every year. Not only is that irresponsible—it’s expensive. Growing, processing, transporting, and disposing that uneaten food has an annual estimated cost of $218 billion, costing a household of four an average of $1,800 annually."

My immediate reaction was that some categories must be getting getting shuffled together here. The emphasis of the public relations campaign and the website is about households savings food. Plan

meals ahead! "Using up leftovers helps the environment." "It’s okay for veggies to wilt and soften. Really. It happens with time and doesn’t mean they’re bad." "Keep herbs like cut flowers – with their stems in a glass of water." "Use a slice of bread to soften up hardened brown sugar."

All fair enough, I suppose. But as a member of a family of five that eats most of its meals at home, I simply don't believe that we are on average throwing away "400 pounds of food per person per year." That would be more than a pound of food per day for each of us, every day. That's not plausible. (We compost much of our organic waste, and we would know.)

Instead, my strong suspicion--confirmed by a closer reading of the NDRC report--is that the category of household food waste is getting shuffled together with all food waste that happens in every stage of the food industry: in farm fields, storage, processing, wholesale, retail, restaurants, cafeterias, and so on. For another fact-filled website on food waste, see the ReFed web\site: ReFED is a collaboration of over 50 business, nonprofit, foundation, and government leaders committed to reducing food waste in the United States.

Two main sets of reasons are given for prioritizing a reduction in food waste. One is the environmental costs of food production and waste disposal.The other is the ongoing presence of hunger in America. Both issues are worthy of concern. But I am unpersuaded that eating softened vegetables, keeping our herbs like cut flowers, and using bread to soften up our hardened brown sugar is much of an answer to either concerns.

(It may help if you read the rest of the memo in the tone of an outraged 11 year-old, upon being told to finish his vegetables because there are hungry people in the world.)

1) The environmental protection goal is based on less overall food being consumed. But the feed-the-hungry goal is based on existing food being transferred to those who don't now have it. The goal of less food consumed is different and not aligned with the goal of transferring food to those who need it.

2) Telling households that they are wasting $1500 per year in the food they purchase for home is incorrect, because food saved from farm fields and processing plants and restaurants doesn't help my household budget.

3) Most households would be better off monetarily and health-wise if they ate more at home, rather that grabbing meals and snacks from restaurants. If people end up tossing some dodgy aged vegetables now and again, at least they were trying to eat some food found in nature. Telling people about how money spent on food at home is often wasted is not necessarily an incentive to spend more on food at home!

4) The environmental costs of food production are real. There is a long list of ways to address issues of water use, energy use, fertilizer runoff, land erosion, and other issues. Working to reduce the total quantity of food demanded is not obviously the most effective approach.

5) The problem of hunger and malnourishment in certain US populations is real. But the practical answers aren't about reducing household food waste. Instead, they involve greater buying power for low-income families and assuring an availability of food, together with education to help these families spend food resources more effectively--which will often involve more meals eaten at home and, yes, some additional food thrown away at home.

6) The notion of "waste" can be elusive. There are economic reasons that some amount of food might be left unharvested in a field, or thrown away from a restaurant. An economist is tempted to infer that "waste" really means "not worth the costs of saving it." In the autumn it can be better to buy a large number of fresh apples, even if a few end up going to waste, rather than to risk running out of fruit on a Wednesday night with no time to shop, or not having enough on hand to make an apple crumble.

At the end of the day, it's of course hard to oppose reducing waste. But I'm mildly allergic to policy discussions based on a combination of misleading statistics and finger-shaking mini-sermons, like this newest version of the Clean Plate Club.