The theme here is that debt isn't necessarily a problem in itself. But when (not if) a bad economic shock hits, then high levels of debt can amplify a moderate economic problem into a severe one. Robert S. Kaplan explores the issue of "Corporate Debt as a Potential Amplifier in a Slowdown" (March 05, 2019). Kaplan is from the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, and he's one of those from the regional Federal Reserve Banks who rotates back and forth between being a voting member and an alternate on the Federal Open Market Committee--the committee that decides whether interest rates will be rising or falling. Here are some points he makes:

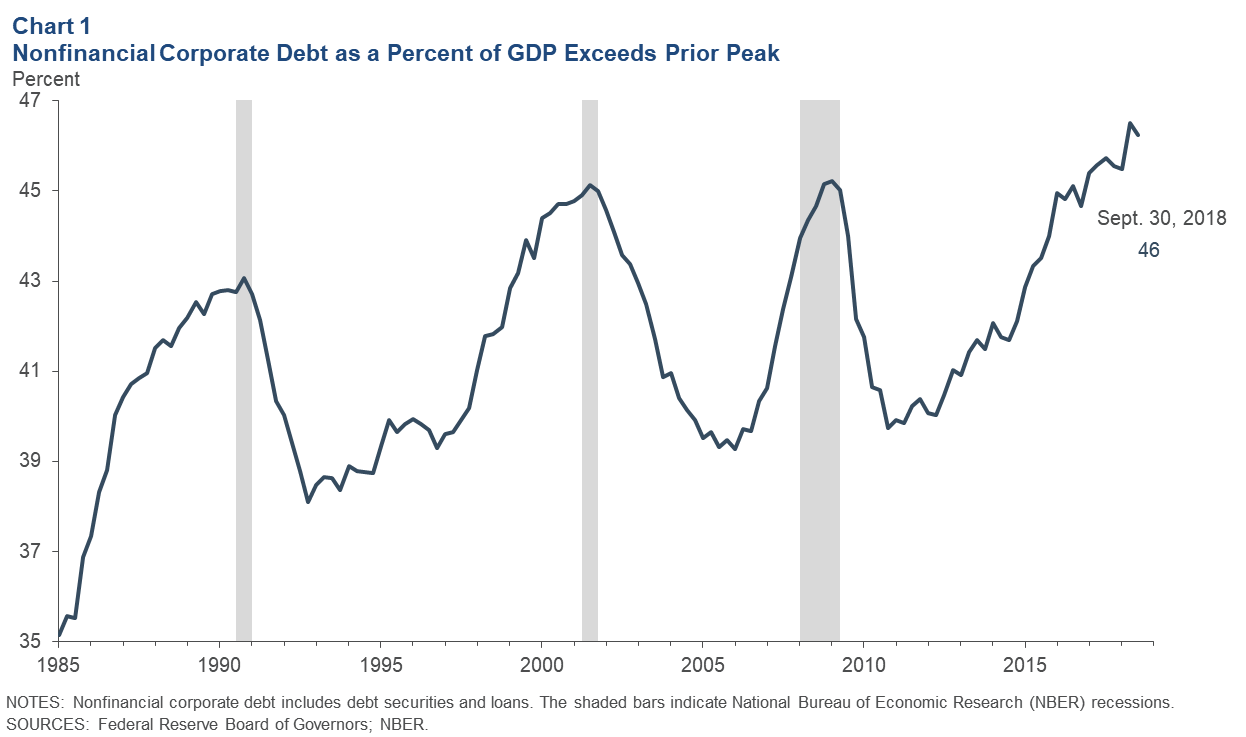

Nonfinancial corporate debt as a share of GDP is up. It's higher than it was at the three previous peaks--each of which preceded a recession. That is, this isn't just a matter of banks lending back and forth to each other, or to other financial institutions.

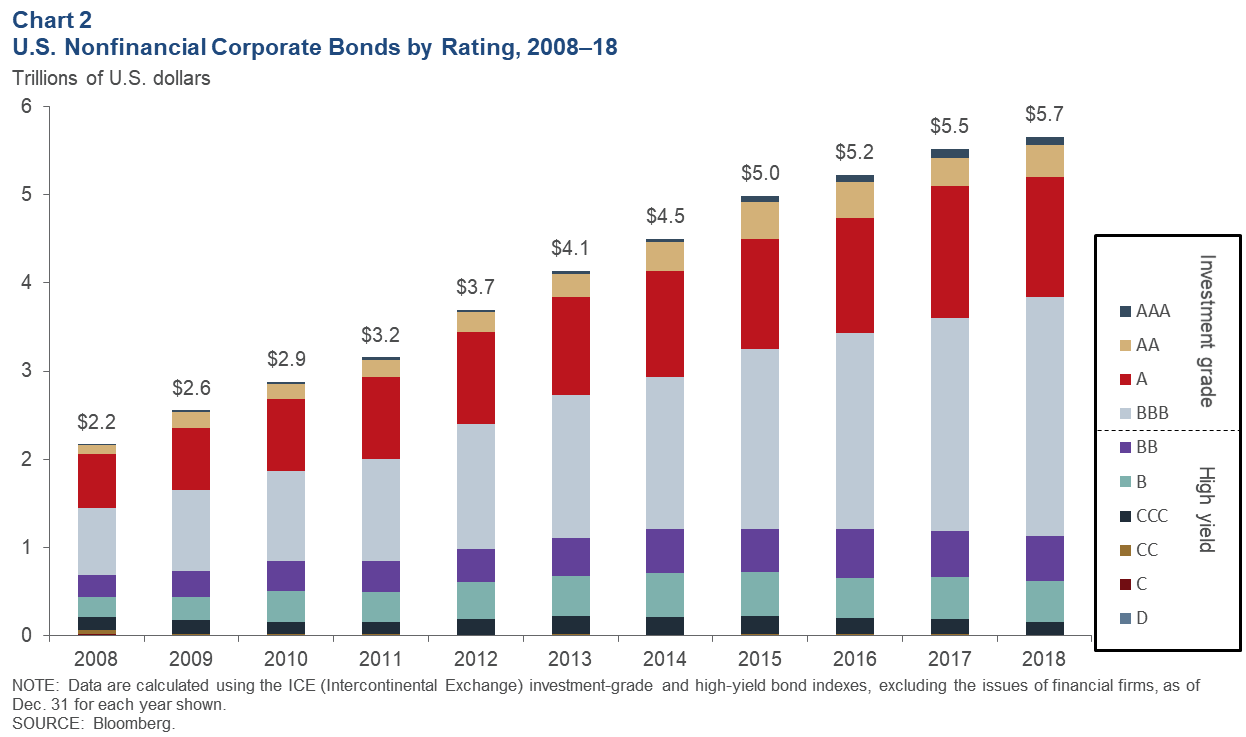

How are companies borrowing? One method is by issuing bonds. the figure shows that the total corporate bonds outstanding is way up in the last 10 years, now at about $5.7 trillion. In particular, bonds rated BBB are way up--the rating that is the lowest possible for a bond to still be treated as "investment grade" rather than "high-yield."

Corporations are also taking out more loans. However, many of these loans are called "leveraged loans." A group of banks get together and arrange a loan to a company--often a company with fairly high risks that would prefer not to issue bonds Then the banks combine these leveraged loans into a CLO, a "collateralized loan obligation."

There's nothing new about combining a bunch of loans into a financial security, which can then be purchased by a wide variety of investors like pension funds, private equity funds, and others. The twist comes when the CLO is broken into "tranches." As an example, say that a CLO is broken into 100 pieces and sold to investors. However, the deal arranged in advance is that if the pool of loans as a whole suffers losses of up to, say, 10%, all of these losses are carried one group of investors. If the losses exceed 10%, this first group of investors is wiped out, and if losses rise to 15%, then these losses are borne by a second group of investors. When this second group is wiped out, then losses from 15-20% are borne by a third group of investors, and so on. Looking at this from the top of the pyramid, there are a group of investors who will keep getting payments from the CLO as scheduled until losses of 40% or even more are experienced.

If you have invested in a CLO knowing that are on the hook for the first 10% of losses, then that is quite a risky financial security. But if you have invested in a CLO knowing that someone else will bear the first 40% of losses, then your CLO investment is actually rated AAA, based on the likelihood that your money is quite safe.

In this way, it's possible for financial institutions to start off with a bunch of fairly risky floating-rate loans to companies, combine them, tranche them, and end up with a situation where 60% or so of the total value of the debt is AAA-rated. This is what happened in the lead-up to the Great Recession with subprime mortgages: combine into what were called "collateralized debt obligations," tranched and sold. But problems arose for the banking and financial sector when it looked as if a certain amount of lending that had been AAA-rated appeared to be running a substantial risk of default.

The other financial issue to which we all became attuned back in 2008 is "rollover risk." Say that a company has borrowed money for a fairly short period, perhaps days or months, with the idea that when the debt comes due, it will just borrow more money to repay the first debt. Again, there's nothing fundamentally wrong with taking a strong of short-term loans, rather than one longer-term loan. But it does create rollover risk: What if when a firm go to borrow the latest round of money, its financial situation looks worse (perhaps because of some other negative economic shock), and so it becomes impossible for the firm to borrow (or perhaps to borrow only at a prohibitive interest rate). The firm then cannot repay its earlier loans, and may need to default. The collateralized loan obligations that included loans from that firm start handing out losses. The ratings for bond issued by the firm decline, and all that BBB-rated borrowing just barely into the "investment grade" category starts falling into the "high-yield" and high risk category.

Here's Kaplan (footnotes omitted):

Leveraged loans are loans made to highly indebted companies and are typically originated by commercial banks and then syndicated to nonbank investors, including special-purpose vehicles such as collateralized loan obligations (CLOs), private equity funds and other stand-alone entities. The size of the syndicated leveraged loan market, which is primarily made up of nonfinancial corporate borrowers, has increased from $0.6 trillion at the end of 2008 to $1.2 trillion at year-end 2018. Much of this increase has occurred to fund corporate acquisitions and private-equity-backed transactions.

In addition to the syndicated leveraged loan market, there is also a direct lending market for leveraged loans in the U.S. This market primarily involves nonbank financial firms—such as asset managers, private equity funds, business development corporations (BDCs), hedge funds, insurance companies and pension funds—lending directly to smaller, mid-market companies. While it is difficult to obtain precise information on the size of this market, Standard and Poor’s (S&P) estimates that the amount of outstanding leveraged loans in the U.S. direct lending market has grown significantly over the past several years and now likely exceeds several hundred billion dollars. ...

The U.S. CLO market has grown from roughly $300 billion at the end of 2008 to $615 billion at the end of 2018. However, it is important to recognize that CLO loan-credit quality today is estimated to be somewhat weaker than 10 years ago.

S&P estimates that in 2018, CLOs and loan mutual funds purchased approximately 60 percent and 20 percent, respectively, of syndicated leveraged loan volumes. It is estimated that less than 10 percent of new issuance was purchased by banks in the U.S. The remaining volumes were purchased by insurance companies, finance companies and others. Because CLOs are today the largest buyer of these syndicated leveraged loans, disruptions to CLO creation could increase the likelihood that leveraged loans remain on bank balance sheets, which could, in turn, limit the ability of affected banks to extend credit during periods of stress.The US corporate debt situation is by no means foreordained to turn into a disaster. But by tightening up on regulation of banks, much of the action in US corrporate borrowing has been shifting into bond markets, the leveraged loan market, and collateralized loan obligations. There are plenty of echoes here of what made a bad economic situation so much worse in 2008, and plenty of reasons for financial regulators to watch carefully as this pot boils.For some earlier comments on these themes, see:

- "Corporate Debt and Leveraged Loans: Financial Snags Ahead?" (September 21, 2018)

- "The Dramatic Expansion of Corporate Bonds" (June 21, 2018)