But why was a deduction for charitable contributions first included in the tax code in 1917? And how has it evolved since then? Nicolas J. Duquette tells the story in "Founders’ Fortunes and Philanthropy: A History of the U.S. Charitable-Contribution Deduction" (Business History Review, Autumn 2019, 93: 553–584, not freely available online, but many readers will have access through library subscriptions).

In the first years of the income tax, less than 1 percent of households were subject to it, and it had rates no higher than 15 percent. Quickly, however, the tax became an important revenue instrument; in 1917 the top rate was abruptly raised to 67 percent to pay for World War I. The Congress added a deduction for gifts to charitable organizations to the bill implementing these high rates, not to encourage the wealthy to give their fortunes away (which the most influential and richest men were already doing) but to not discourage their continued giving in light of a larger tax bill. Senator Henry F. Hollis of New Hampshire—who was also a regent of the nonprofit Smithsonian Institution—proposed that filers be permitted to exclude from taxable income gifts to “corporations or associations organized and operated exclusively for religious, charitable, scientific, or educational purposes, or to societies for the prevention of cruelty to children or animals.” The senator argued for the change not because he thought it was wise public policy to change the “price” of charitable contributions via a subsidy but because of worries that reduced after-tax income of the very rich would end their philanthropy, shifting burdens the philanthropists had been carrying onto the backs of a wartime government. ... Hollis’s amendment to the War Revenue Act of 1917 was accepted unanimously and without controversy.Notice the implication here that charitable contributions can reasonably be viewed as a one-for-one offset for government spending. The next inflection point for the charitable contributions deduction happens after World War II. The top income tax rates have risen very high. As a result, it was literally cheaper to give money to charity than to pay taxes--at least for that select group of taxpayers with very high income levels in the top tax brackets, and especially business leaders who held much of their wealth the form of corporate stock that would incur large capital gains taxes if sold. Duquette writes:

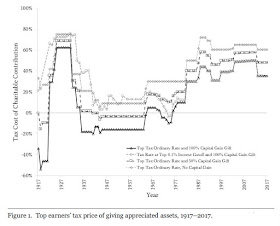

For the very rich, especially entrepreneurs like Carnegie and Rockefeller who grew their wealth through business expansion, charitable gifts of corporate stock avoided multiple taxes. Most obviously, their giving reduced their income tax, but under the deduction’s rules such gifts additionally avoided capital gains taxation. Furthermore, wealth given away was wealth not held at death, so giving during life also reduced the size of the donor’s taxable estate. When the U.S. Congress raised income tax rates to pay for the war and defense costs of the mid-twentieth century, it created a situation where many of the richest American families found that by giving their fortunes to a foundation they avoided more in taxation than they would have received in proceeds for selling shares of stock. Foundations flourished. ... [F]or several years in the middle of the twentieth century, it was quite possible for stock donations to be strictly better than sales of shares for households with high incomes and high capital gains.Here's an illustrative figure from Duquette. He explains:

Figure 1 plots the tax price of donating stock for various high-income tax brackets and capital gains ratios over the period 1917–2017. During World War I and for several years following World War II, wealthy industrialists with large unrealized capital gains facing the very highest tax rates were better off donating shares than selling them, even if they had no interest in philanthropy. Taxpayers with lower θ [a measure of the degree of capital gains available to the potential donor] or with taxable incomes not quite in the highest tax bracket may not have been literally better off making a donation in each of these years, but they nevertheless surrendered very little after-tax income by making a donation relative to selling their stock. Note, too, that this figure presents only tax savings relative to federal income and capital gains taxation; many donors quite likely received additional savings in the form of charitable-contribution deductions from state income taxation and by reducing their taxable estates.

The surge of charitable giving by the wealthy in the 1950s and into the 1960s, in response to these tax incentives, led to two counterreactions.

One was that those with high incomes began to use charitable foundations as a way of preserving family wealth and power.

Before 1969, there were few checks on the governance of family foundations or their handling of shareholder power. To entrepreneurs who had built large enterprises from scratch, the foundations presented an appealing way to have the benefit of selling shares without losing control of the business. Corporate shares sold to strangers could not be voted in line with the seller’s preferences; shares given to heirs and the heirs of heirs could lead to familial factionalism and, eventually, sales of shares by the least committed cousins; but a family foundation holding shares of stock and voting those shares as a bloc could maintain family control of a firm, however much the siblings and cousins may have squabbled at the foundation’s board meetings. Even better, family foundations could pay family members generous salaries to direct and manage the foundation, allowing them to continue to benefit from the profits redounding to the foundation’s stockholding. Although many industrialists gave directly to specific charities, the foundation vehicle had the additional benefit of being able to leave corporate control to one’s heirs through a single untaxed legal entity. Without the structure of a foundation, meeting the costs of the estate tax might force a family to sell shares below the 51 percent level of corporate control, or heirs might not coordinate their share voting as a bloc. ...

A 1982 survey found that half of the largest foundations established from 1940 to 1969 were begun with a gift of stock large enough to control a firm and that founders rated tax motivations as an important factor. This was true for few foundations established before 1939, when the wealthy would not have been better off giving than selling their shareholdings. ... Some corporate foundations were demonstrated to have made loans at below-market rates or to have made other suspicious business deals with their sponsoring firms.44 Private foundations further extended the insider control of corporations through maneuvering to conceal financial information or consolidate votes during shareholder elections.45 Of the thirteen largest foundations that accounted for a large share of all foundation assets, twelve were controlled by a tight-knit and highly interlocked “power elite,” undermining the case that tax benefits to foundations served the public.

These use of charitable foundations became something of a scandal, and were highly restricted or outlawed by the Tax Reform Act of 1969.

The other counterreaction, related to the first, was a growing awareness that the deduction for charitable contributions was really a tax break for the rich. Taxpayers have a choice when filling out their taxes: they can take the "standard deduction," or they can itemize their deductions. The usual pattern in recent decades has been that only about one-third of tax returns itemize deductions, and those tend to be people with higher incomes (who also have a lot of other deductions large enough to make itemizing worthwhile). In addition, a person in the highest tax brackets saves more money from an additional $1 of tax deductions than a person in lower tax brackets.

Another important factor is that by the 1970s, the role of government in providing education, health, and support for the poor and elderly had increased quite a lot since the original introduction of the deduction for charitable contributions in 1917. Taking these factors and other together, Duquette explains:

The result was a shift from thelong-standing perspective of policymakers that the deduction protected philanthropic contributions to social goods and saved the Treasury money to a more skeptical and economistic perspective that the deduction was an implicit cost that must be justified by its benefits. ...

In particular, Martin Feldstein’s groundbreaking econometric studies of the deduction’s effectiveness, supported by Rockefeller III, reframed the deduction as a “tax expenditure.” Instead of asking how much less the government needed to spend thanks to philanthropy, Feldstein asked how much the deduction cost the Treasury relative to the additional giving it induced. This tax price (described above) could be quantified relative to “treasury neutrality”—that is, whether it induced more dollars in giving than the federal government lost in tax revenue for having it. Feldstein’s answer was reassuring. He found that the deduction encouraged more giving than it cost in uncollected taxes. But his work elided the long-standing distinction between the philanthropy of the very rich and the mere giving of ordinary people.In the last few decades, the role of the deduction for charitable contributions has been much diminished. Top marginal tax rates were cut in the 1980s, making the deduction less attractive. "Nevertheless, with reduced tax incentives, giving by the rich fell sharply. Households in the top 0.1 percent of the income distribution reduced the share of income they donated by half from 1980 to 1990, concurrent with the reduced value of the deduction over that period. In the aggregate, charitable giving overall fell from just over 2 percent of GDP in 1971 to its lowest postwar level, 1.66

percent of GDP, in 1996."

In addition, the 2017 Tax Cut and Jobs Act increased the standard deduction, and the forecasts are that the share of taxpayers who itemize deductions will fall from about one-third down to one-tenth.

In short, the deduction for charitable contributions is going be be used by a smaller share of mainly high-income taxpayers, and with reduced incentives for using it. A large share of charitable giving--say, what the average person donates to community projects, charities, or their church--doesn't receive any benefit from the charitable contributions deduction. Many of the large charitable gifts no longer provide direct services, as government has taken over those tasks.

It seems to me that there is still a sense that the deduction for charitable contributions provides an incentive for big donations from those with high having incomes and wealth--an incentive that goes beyond good publicity and naming rights. There may also be some advantage in having nonprofits and charities rally support among big donors, rather than relying on the political process and government grants. But it also seems to me that the public policy case for a deduction for charitable contribution is as weak as it has ever been in the century since it was first put into place.