The Federal Reserve, like central banks everywhere, view providing financial liquidity during a crisis (being the "lender of last resort") as one of their core functions. What has the Fed done so far in the COVID-19 recession?. Tim Sablik offers a crisp overview in "The Fed's Emergency Lending Evolves" (Econ Focus: Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, Second/Third Quarter 2020, pp. 14-17).

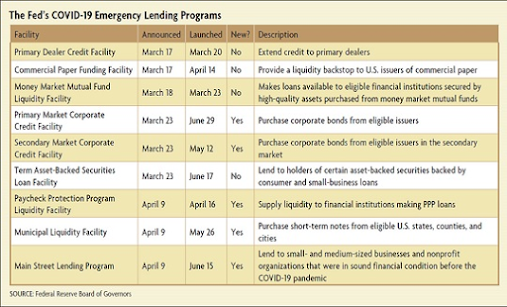

Here's a list of the nine main lending programs the Fed has used, and to whom the credit was extended:

And here's a graph showing how much was loaned under these programs as of August 12. The Main Street Lending Program doesn't appear on this graph because it had loaned $226 million--not enough to show up on a graph measured in tens of billions of dollars.As you can see, total Fed lending spiked very quickly in late March, then eased a little higher in late June and a little lower in early August. A short description of the various lending programs from the Federal Reserve is here; an update on lending through the end of August is here.

In practical terms, the key test of emergency lending is whether it is repaid fairly soon, and thus fades away. When that happens--say, look at the blue Primary Dealer Credit Facility at the bottom of the figure--it suggests that the real problem was a short-term credit crunch, which soon resolved itself when the Fed made emergency loans available. The Money Market Mutual Fund Lending Facility seems on a similar trajectory.

Based on the current data, the real challenge for current lending will be the Paycheck Protection Program Liquidity Facility--the program where the Fed helps banks to make loans to small-ish or at least non-huge companies so that they can meet payroll and not need to lay off workers. The Small Business Administration has the power to forgive these loans; in other words, any losses that arise from loan forgiveness in this program will be attributed to the SBA, not to the Fed.

In broader terms, the key distinction is that it is acceptable for a central bank to be a lender of last resort in a short-term financial market panic, as arguably occurred in March, with the expectations that such loans will be repaid when the market stabilizes. The infamous section 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act is the break-glass-in-case-of-emergency part of the law, which gives the Fed the authority to do "broad-based" lending under ""unusual and exigent circumstances." Section 13(3) got a workout during the Great Recession, and it is the legal justification for all nine of the lending programs above. But as the Fed takes a few halting steps into assuring credit for corporate bond markets and for payroll protection, there is some danger that it is sticking a toe or two over the line of the lender of last resort role, and instead becoming a tool for extending credit in a few favored markets.