The Federal Reserve reduced what had been its main policy-related interest rate, the federal funds reserve rate, down to a target range of 0% to 0.25% at the tail end of 2008, and kept it there until December 2015, when it raised the target range to 0.25% to 0.5%. With this interest rate essentially stuck in place for nearly eight years and still at near-zero levels, what should come next?

The status quo plan seems to call for the Fed to carry out slow and intermittent policy of raising the federal funds rate back to more usual levels over time. But there are two diametrically opposite proposals in the wind, both of them counterintuitive in some ways. One proposal is for the Fed to push its policy interest rate into negative territory. The other "neo-Fisher" proposal is for the Fed to raise interest rates as a tool that seeks to raise inflation. Both proposals have enough uncertainties that that I suspect the Fed will continue along its present path. But here's an overview of the two alternative approaches.

Benoît Cœuré, a member of the Executive Board of the European Central Bank, provided a useful overview "Assessing the implications of negative interest rates," in a July 28, 2016 lecture. Perhaps the first mental hurdle to cross in thinking about negative interest rates is to remember that they are already happening, which does not prove whether they are wise or unwise, but certainly proves that they are not impossible! As he points out, the European Central Bank pushed a key policy interest rate into negative territory in June 2014. The

Swiss National Bank went negative in December 2014. The

Bank of Japan went negative in January 2016.

In some broader sense, it is of course true that financial markets have been accustomed to the idea of negative real interest rates for quite some time After all, back in the 1970s when inflation rose unexpectedly, lots of institutions found that their earlier loans were being repaid with inflated dollars--in effect, real interest rates turned out to be negative. Anyone investing in long-term bonds when the nominal interest rate is positive, but very low, needs to face the very real chance that if inflation rises, the real interest rate will turn out to be negative. If you take checking account fees into account, lots of people have had negative real interest rates on their checking accounts for a long time.

Cœuré offers a figure on government bond yields in different countries (which is not the same as the policy interest rate set by a central bank, but what investors are receiving when they buy a bond), at different maturities. Government bond yields are negative for bonds with shorter-term maturities in a number of countries, although not in the US or the UK.

As I see it, the events that led to negative policy interest rates can be expressed using the basic relationship named after the great long-ago economist Irving Fisher (1867-1947). Fisher pointed out that:

nominal interest rates = real interest rates plus inflation.

Thus, back in the mid-1990s, it was common for US government borrowing to pay a nominal interest rate of about 6% on a 10-year government bond, which one could think of as about 3-4% a real interest rate on a safe asset, and 2-3% the result of inflation. In the last 15 years or so, real interest rates have been driven ever-lower by global macroeconomic forces involving demographics, rates of saving and investment, rising inequality, an increased desire for ultra-safe assets, and other forces. (For a discussion, see this post on

"Will the Causes of Falling Interest Rates Unwind?" from February 25, 2016). Inflation rates have of course been very low in the last few years as well, especially since the Great Recession and the sluggish recovery that followed.

When real interest rates and inflation are both very low, nominal interest rates will also be low. Thus, when a central bank wants to cut interest rates, it will very quickly reach an interest rate of 0%--and need to start thinking about the possibility of negative rates.

But although negative interest rates are now real, and not hypothetical, just how much they can accomplish remains unclear. After all, it seems unlikely that the reasons for a lack of lending and borrowing--whatever they are--will be profoundly affected by having the central bank policy interest rate shift from barely above 0% to barely below 0%. Thus, the question becomes whether to push the negative interest rates lower still. Cœuré discusses possible tradeoffs here.

For example, one issue is whether economic actors start holding large amounts of cash, which at least pays a 0% interest rate, to avoid the negative rates. At least at the current levels of negative interest rates, this hasn't happened. As noted already, actual real interest rates have often been negative in the past. Although Cœuré doesn't discuss this point in any detail, there's some survey evidence that

people (and firms) may react to negative interest rate by saving more and having a bigger cash cushion, which would tend to work against such low rates stimulating borrowing and spending.

Instead, Cœuré focuses on the issue of whether there is what he calls an "economic lower bound," where the potentially positive effects of negative interest rates in encouraging banks to lend are offset by potentially negative effects. He looks at evidence on the sources of profits for euro-area banks, and finds: "In recent years, the distribution of these sources has been fairly stable, with approximately 60% of income coming from net interest income, 25% from fees and commissions and 15% from other income sources."

"Net interest income" basically means that a bank lends money out at an interest rate of, say, 3%, but then pays depositors an interest rate of, say, 1%--and thus earns revenue from the gap between the two. But as interest rates fall in general and in some cases go negative, the interest rate that banks can charge borrowers is dropping, but banks don't feel that they can pay negative interest rates to their depositors, so those interest rates--already near-zero--can't fall. Thus, the main source of bank revenues, net interest income, is squeezed. On the other side, the lower and negative interest rates also benefit banks in some ways, both on their balance sheets, and also because if the economy is stimulated, banks will face fewer bad loans. But as these processes unfold, the banking sector can be shaken up. Cœuré writes:

Indeed, analysts forecast a decline in bank profitability in 2016 and 2017, mainly due to lower net interest income. And the recent decline in euro area bank share prices can be at least partially ascribed to market concerns over future banks profitability. ... As such, if very low or negative rates are here for a prolonged period of time due to the structural drivers highlighted above, banks might have to rethink their business models. The revenue structure of euro area banks was stable for a long time but it has recently begun to change and there is at least some evidence of banks tending to offer fee-based products to clients as substitutes for interest-based products.

The overall irony here is that there has been enormous concern in recent years over the risks of an unhealthy banking industry, and a common recommendation has been to require banks to build up their capital, so that they won't be as vulnerable to economic downturns and won't need payouts. But when a central bank uses a negative policy interest rate, it is saying that banks will not be receiving interest on a certain subset of their funds, but instead will be paying out money on a certain subset of their funds. When higher-ups at the European Central Bank start talking about how all the euro-area banks "might have to rethink their business models," that's not a small statement. For some more technical research on how to think about when harms to the banking sector might outweigh other benefits, a useful starting point is a working paper by

Markus K. Brunnermeier and Yann Koby, “The “Reversal Rate”: Effective Lower Bound on Monetary Policy,” presented at a Bank of International Settlements meeting on March 14, 2016.

There are other uncertainties about very low and negative-yield interest rates. If a government decides that it wants to borrow heavily for a fiscal stimulus, does this at some point become difficult to do if the government is offering very low or negative interest rates? Certain policy steps might make sense for a smaller economy like Switzerland, where the central bank is in part using the policy interest rate to affect its exchange rate, but might not make sense for the mammoth US economy. The Fed has no desire to risk setting off off a pattern of central banks around the world competing to offer ever-more-negative interest rates. Taking all this together, I expect that while negative policy interest rates will continue in Europe for some time, concerns about financial sector stability and other issues means that they are unlikely to be adopted by the US Federal Reserve. Fed vice-chair

Stanley Fischer made a quick and dismissive reference to negative interest rates in a talk on the broader economy last week, saying that "negative interest rates" were "something that the Fed has no plans to introduce." Of course, "has no plans" doesn't mean "will never do it," but the current policy of the Fed calls for a slow rise its policy interest rate, not decline.

For a full-scale tutorial on the state of thinking about central banking and negative interest rates, a useful starting point is at

June 6 symposium on "Negative Interest Rates: Lessons Learned ... So Far," which was held by the Hutchins Center on Fiscal and Monetary Policy at Brookings. The weblink has full video for about three hours of the session, together with a transcript and slides from the speakers.

The polar opposite to negative interest rates is the idea of raising interest rates as a way of increasing inflation, a set of arguments which is considerably more counterintuitive than the case for negative interest rates.

Stephen Williamson provides a readable overview of these arguments in "Neo-Fisherism: A Radical Idea, or the Most Obvious Solution to the Low-Inflation Problem?" which appears in the July 2016 issue of

The Regional Economist, published by the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (pp. 4-9 offers a primer for understanding the neo-Fisherian argument. Again, neo-Fisherian refers to the relationship invoked by the famous economist between nominal interest rates and inflation:

nominal interest rates = real interest rate + rate of inflation.

This relationship isn't mysterious. When anyone lends or borrows, they pay attention to the expected rate of inflation. Lots of people took out home mortgages at 12% and more back in the early 1980s, because inflation had recently been 10% and higher, so they expected to be able to pay off the mortgage in inflated dollars. In modern times, of course, it would seem crazy to borrow money at a 12% interest rate, given that inflation is down in the 1-2% range.

When the Federal Reserve raises the nominal interest rate, what does the Fisher relationship suggest

could happen? One theoretical possibility is that the rate of inflation changes to match the change in the nominal interest rate. This theoretical possibility, called the "neutrality" of money, suggests that the Fed can raise or lower nominal interest rates all it wants, but there won't be any actual effect on real interest rates. However, the evidence suggests that monetary policy isn't completely neutral. Instead, if the Fed changes interest rates, then the real rate of interest also changes for a time, which is why monetary policy can affect the real economy. But if the real interest rate is ultimately determined as a market price in the global economy, then any change due to the central bank will be short-run, and the real interest rate will eventually return to its equilibrium level.

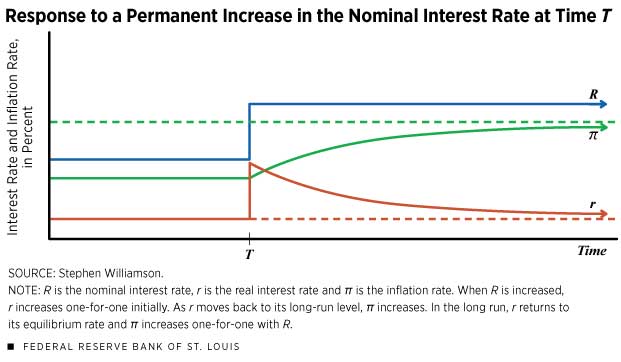

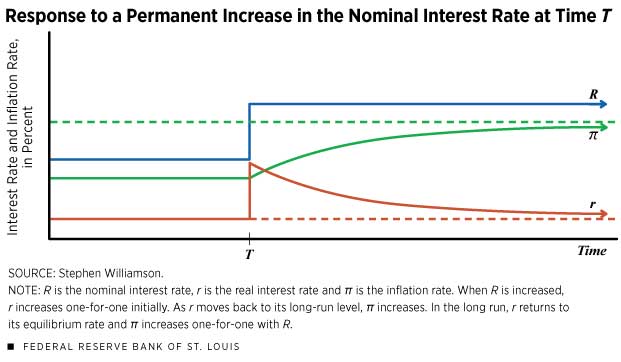

Based on this idea, here's a figure from Williamson to describe the theory of neo-Fisherism. On the far left, the red line shows the real interest rate, the green line shows the rate of inflation, and if you add these together you get the blue line that shows the nominal interest rate. At time T, the Fed raises the nominal interest rate. Because of the nonneutrality of money, the real interest rate r shown by the red line rises, too. But over time, the real interest rate is then pushed by underlying market forces back to its original equilibrium level. However, if the Fisher relationship must hold true, then the drop in the real interest rate must be matched by a rise in the inflation rate shown by the green line. (Those who want a more detailed mathematical/theoretical presentation of these arguments might begin with

John Cochrane's Hoover Institution working paper from February 2016, "Do Higher Interest Rates Raise or Lower Inflation?")

Neo-Fisherism offers a possible explanation of how some central banks around the world ended up in their current situation. The Fed cut interest rates, because it sought to stimulate the economy and avoid deflation. But by cutting interest rates, the Fed according to neo-Fisherism instead brought on lower inflation. The Bank of Japan has had rock-bottom interest rates for years, and negative interest rates recently, while inflation has stayed rock-bottom and even occasional deflation has occurred. Rock-bottom and even negative interest rates don't seem to have caused inflation in Europe, either. Williamson refers to this outcome as the "low inflation policy trap."

However, neo-Fisherism also raises some obvious questions: Why are we trying to achieve a goal of higher inflation? Doesn't that jolt of rising real interest rates in the short-term risk causing a recession?

On the issue of inflation, there has long been a concern that deflation is a legitimate cause for worry. After all, deflation means that everyone who has borrowed money at a fixed interest rate in the past would now be facing a higher real interest rate. On the other side, a few percentage points of inflation would mean that everyone who borrowed at fixed interest rates in the past would be able to repay in inflated dollars, thus, reducing the burden of their debts. In addition, very low inflation combined with what have now become very low real interest rates means that the Fed can't react to a recession by cutting nominal interest rates--at least not without entering the swamp of negative interest rates. Williamson describes the arguments this way:

"There are no good reasons to think that, for example, 0 percent inflation is worse than 2 percent inflation, as long as inflation remains predictable. But "permazero" damages the hard-won credibility of central banks if they claim to be able to produce 2 percent inflation consistently, yet fail to do so. As well, a central bank stuck in a low-inflation policy trap with a zero nominal interest rate has no tools to use, other than unconventional ones, if a recession unfolds. In such circumstances, a central bank that is concerned with stabilization—in the case of the Fed, concerned with fulfilling its "maximum employment" mandate—cannot cut interest rates. And we know that a central bank stuck in a low-inflation trap and wedded to conventional wisdom resorts to unconventional monetary policies, which are potentially ineffective and still poorly understood."

What about the risk that a spike in real interest rats could bring financial disruptions and even a recession? Williamson's essay doesn't discuss the possibility. Perhaps if the Fed described what it was going to do, and why it was going to do it, the spike in real interest rates might be smaller. But the risks of neo-Fisherism seem like a real danger to me. Among other changes, neo-Fisherism would be a very dramatic change in Fed policy, and for that reason alone it has the potential to be highly destabilizing at least in the short run.

So if the Federal Reserve is trapped between not wanting to go with negative interest rates on one hand, but also not believing in neo-Fisherism on the other hand as a justification for a dramatic rise in interest rates, what does it do. For some context, consider the unemployment rate (blue line) and inflation rate (red line) in the last few years. Unemployment has been drifting lower. The inflation rate was up around 2% in early 2014, but then dropped down to near-zero, in part as a result of t

he sharp fall in oil prices during that time. After that fall in oil prices was completed, inflation went back up to about 1% by late 2015. Not coincidentally, the Fed also raised its target for the federal funds interest rate in December 2015. The Fed is taking a wait-and-see stance, but my guess is that if inflation goes up to the range of about 2%, the Fed will view this as an opportunity to raise its nominal interest rate target a little higher. That is, instead of the neo-Fisherism view in which raisint the nominal interest rate brings on higher inflation, the Fed is instead letting inflation go first, and raising the interest rates afterward.

Essentially, the Fed is trying to creep back to a range in which nominal interest rates are closer to the historical range. But if real interest rates remain low, because of various evolutions in the global economy, then nominal interest rates can only be higher if the inflation rate rises by a few percentage points.