Daniel Hartley, Anna Paulson, and Katerina Powers look at recent patterns of life insurance and bring the puzzle of its decline into sharper definition in "What explains the decline in life insurance ownership?" in Economic Perspectives, published by the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago (41:8, 2017). The story of shifting attitudes toward life insurance in the 19th century US is told by Viviana A. Zelizer in a wonderfully thought-provoking 1978 article, "Human Values and the Market: The Case of Life Insurance and Death in 19th-Century America," American Journal of Sociology (November 1978, 84:3, pp. 591-610).

Early the 19th century, the costs of death and funerals were largely a family and neighborhood affair. As Zelizer points out, attitudes at the time, life insurance was commercially unsuccessful because it was viewed as betting on death. It was widely believed that such a bet might even hasten death, with with blood money being received by the life insurance beneficiary. For example, Zelizer wrote:

"Much of the opposition to life insurance resulted from the apparently speculative nature of the enterprise; the insured were seen as `betting' with their lives against the company. The instant wealth reaped by a widow who cashed her policy seemed suspiciously similar to the proceeds of a winning lottery ticket. Traditionalists upheld savings banks as a more honorable economic institution than life insurance because money was accumulated gradually and soberly. ... A New York Life Insurance Co. newsletter (1869, p. 3) referred to the "secret fear" many customers were reluctant to confess: `the mysterious connection between insuring life and losing life.' The lists compiled by insurance companies in an effort to respond to criticism quoted their customers' apprehensions about insuring their lives: "I have a dread of it, a superstition that I may die the sooner" (United States Insurance Gazette [November 1859], p. 19). ... However, as late as the 1870s, "the old feeling that by taking out an insurance policy we do somehow challenge an interview with the 'king of terrors' still reigns in full force in many circles" (Duty and Prejudice 1870, p. 3). Insurance publications were forced to reply to these superstitious fears. They reassured their customers that "life insurance cannot affect the fact of one's death at an appointed time" (Duty and Prejudice 1870, p. 3). Sometimes they answered one magical fear with another, suggesting that not to insure was "inviting the vengeance of Providence" (Pompilly 1869). ... An Equitable Life Assurance booklet quoted wives' most prevalent objections: "Every cent of it would seem to me to be the price of your life .... it would make me miserable to think that I were to receive money by your death .... It seems to me that if [you] were to take a policy [you] would be brought home dead the next day" (June 1867, p. 3)."However, over the course of several decades, insurance companies marketed life insurance with a message that it was actually a loving duty to one's family for a devout husband. As Zelizer argues, the rituals and institutions of what society viewed as a "good death" altered. She wrote:

"From the 1830s to the 1870s life insurance companies explicitly justified their enterprise and based their sales appeal on the quasi-religious nature of their product. Far more than an investment, life insurance was a `protective shield' over the dying, and a consolation `next to that of religion itself' (Holwig 1886, p. 22). The noneconomic functions of a policy were extensive: `It can alleviate the pangs of the bereaved, cheer the heart of the widow and dry the orphans' tears. Yes, it will shed the halo of glory around the memory of him who has been gathered to the bosom of his Father and God' (Franklin 1860, p. 34). ... life insurance gradually came to be counted among the duties of a good and responsible father. As one mid-century advocate of life insurance put it, the man who dies insured and `with soul sanctified by the deed, wings his way up to the realms of the just, and is gone where the good husbands and the good fathers go' (Knapp 1851, p. 226). Economic standards were endorsed by religious leaders such as Rev. Henry Ward Beecher, who pointed out, `Once the question was: can a Christian man rightfully seek Life Assurance? That day is passed. Now the question is: can a Christian man justify himself in neglecting such a duty?' (1870)."Zelizer's work is a useful reminder that many products, including life insurance, are not just about prices and quantities in the narrow economic sense, but are also tied to broader social and institutional patterns.

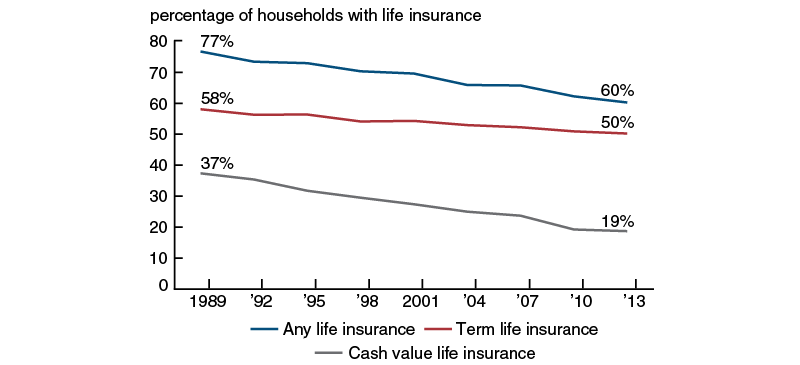

The main focus of Hartley, Paulson, and Powers is to explore the extent to which shifts in socioeconomic and demographic factors can explain the fall in life insurance: that is, have socioeconomic or demographic groups that were less likely to buy life insurance become larger over time? However, after doing a breakdown of life insurance ownership by race/ethnicity, education level, and income level, they find that the decline in life insurance is widespread across pretty much all groups. In other words, the decline in life insurance doesn't seem to be (primarily) about socioeconomic or demographic change, but rather about other factors. They write:

"Instead, [life insurance] ownership has decreased substantially across a wide swath of the population. Explanations for the decline in life insurance must lie in factors that influence many households rather than just a few. This means we need to look beyond the socioeconomic and demographic factors that are the focus of our analysis. A decrease in the need for life insurance due to increased life expectancy is likely to be an especially important part of the explanation. In addition, other potential factors include changes in the tax code that make the ability to lower taxes through life insurance less attractive, lower interest rates that also reduce incentives to shelter investment gains from taxes, and increases in the availability and decreases in the cost of substitutes for the investment component of cash value life insurance."

It's intriguing to speculate about what the decline in life insurance purchases tells us about our modern attitudes and arrangements toward death, in a time of longer life expectancies, more households with two working adults, the backstops provided by Social Security and Medicare, and perhaps also shifts in how many people feel that their souls are sanctified (in either a religious or a secular sense) by the purchase of life insurance.