Some hard questions defy easy answers. What is the meaning of life? What happens right at the event horizon of a black hole? How can the US substantially reduce health care spending? But for other questions, the answers are fairly clear, and what is lacking is a willingness to choose. Fixing Social Security falls into this category. As I have argued from time to time in the past, the actuaries at Social Security regularly publish a list of possible tax increases and benefit cuts, and its not hard to put together a package that fixes Social Security. I sometimes say that if we locked a group of 100 randomly chosen people in a room, and said they couldn't leave until they had a two-thirds majority for a plan to fix Social Security, they could be out in time for lunch.

"With reserves that accumulated in previous years to supplement annual payroll taxes, Social Security can cover all of the benefits that workers claim through 2034. After that, the reserves will be used up and projected revenues will only cover about three-quarters of the benefits to which workers are legally entitled. Some combination of higher payroll taxes, lower benefits and new revenue sources will be needed to balance the books."

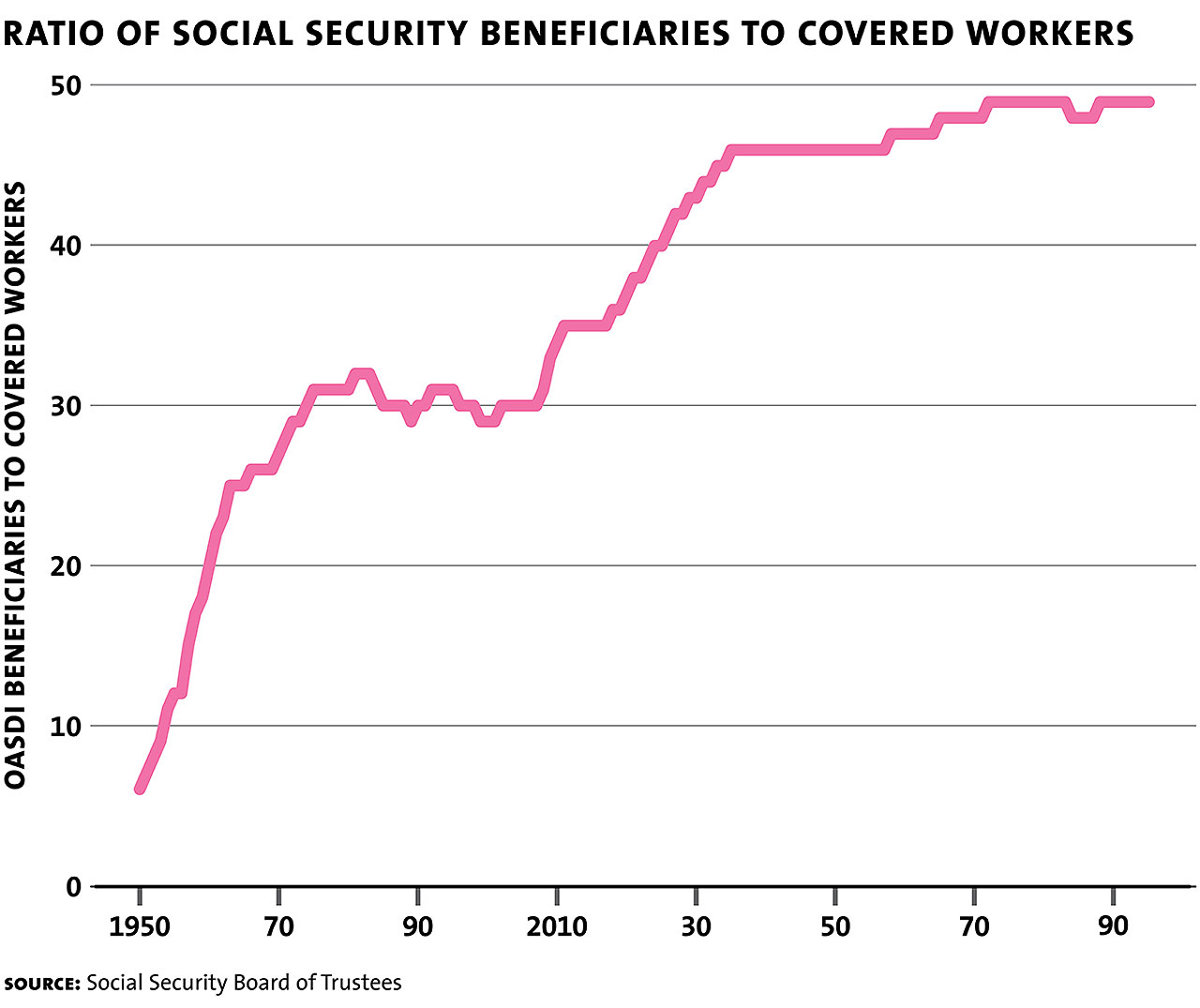

A couple of figures may help to illustrate the underlying problem. The front end of the "baby boom" generation, born from 1946 up through the early 1960s, started hitting retirement age in 2010. Life expectancies are up. From about 1970 to 2010, there were about 30% as many beneficiaries as workers contributing to the system; but by 2030, there will be 45% as many beneficiaries as workers. To put it another way, the ratio of payroll tax contributors to beneficiaries was about 3:1, and it's heading for close to 2:1.

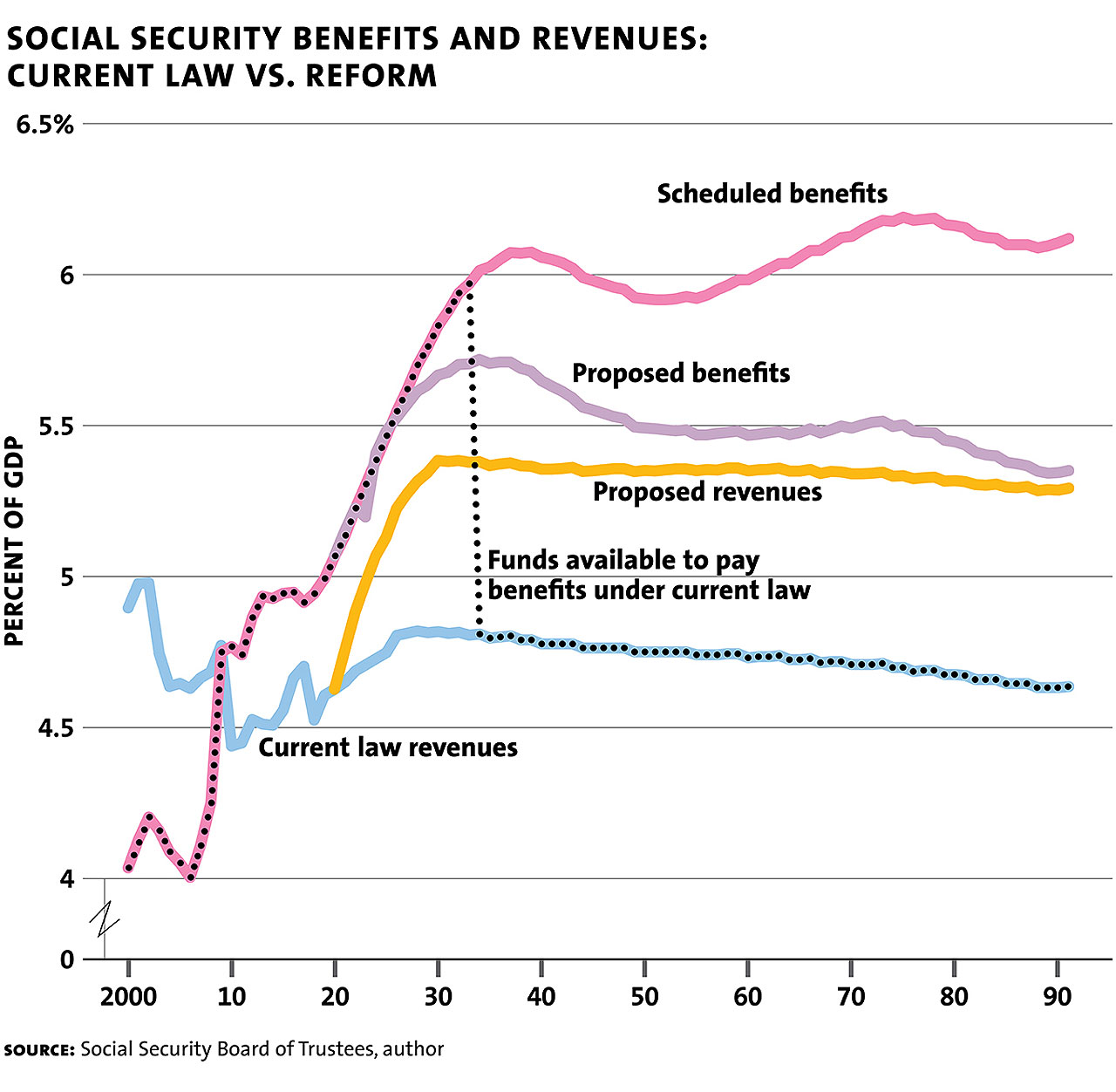

Looking at the path of spending and revenues in Social Security shows the result. Back in 2000, revenues into the system exceeded outflows, which is the period when the trust fund is being built up. But back around 2010, the lines cross, so outflows exceed revenues and the trust fund is being depleted. In 2034, as shown by the vertical dashed line, the trust fund runs out. The figures shows scheduled benefits and revenues, and it also shows Gale's proposed plan for getting them to meet.

I should note that Gale's plan is, as he notes, actually from a report by the Bipartisan Policy Center, Securing Our Financial Future: Report of the Commission on Retirement Security and Personal Savings, published in June 2016. The five main ingredients include:

Raise the Payroll Tax Cap

In 1977, the payroll tax cap was set at 90 percent of wages in the economy and was indexed to grow in tandem with average wages. Since then, however, average wages have grown only modestly while the wages of high-earners have charged ahead. Consequently, by 2016, Social Security taxes covered only 83 percent of total wages. Under the commission’s proposal, the taxable earnings cap would be raised to cover 86 percent of wages by the end of 2024. Thereafter, the cap would be indexed to the growth in average wages, plus half a percentage point annually. ...

Tax More of the Benefits of High-Income Households

Currently, people with incomes above $25,000 if single ($32,000 if married) owe income taxes on a portion of their Social Security benefits, with the taxable share peaking at 85 percent. The commission proposes to tax high-income households (singles with income above $250,000 and married couples with income above $500,000) on 100 percent of their benefits. ...

Raise the Payroll Tax Rate

The commission would lift the payroll tax rate by 0.1 percentage points each year for the next decade, peaking at 13.4 percent. That is, employees and employers would each eventually pay 6.7 percent of wages below the taxable cap, up from 6.2 percent today. ...

Raise the Full Retirement Age

The package would increase the full retirement age by one month every two years starting in 2027, until it reaches 69. The rationale is simple: people are living longer. For example, 20-year-olds in 2014 were expected to live to age 80, while 20-year-olds in 1950 were expected to live to just age 71. ,,, [A]s we raise the full retirement age, we should not raise the age (now 62) at which retirees can begin receiving early benefits. Increasing the early retirement age would disproportionally hurt those who find it especially hard to work past age 62 — notably, manual laborers with minor age-related disabilities.

Protect Low-Income Beneficiaries and Make Benefits More Progressive

Because low-income workers would experience benefit cuts resulting from a higher retirement age, the commission’s reforms include several provisions to offset the impact. First, it would make the annual benefit formula more progressive ... Second, it would raise minimum benefits. A single person with a monthly benefit of $500 today would get an increase to $784. The boost would decline as benefits rise, and it would disappear once benefits for a single retiree reached about $900 per month ($1,360 for couples).For some years, I've thought that fixing Social Security offers the possibility of a big political win for the party that is willing to take the task seriously. The program is very popular, and provides income to about 60 million mostly elderly and disabled Americans. Democrats could have proposed a serious plan in the time window of 2009-2010, when they controlled Congress, and Republicans could have proposed a serious plan from 2016-2018, when they controlled Congress. Surely, being the party that saved Social Security would be worth some political points?

Perhaps what needs to be defended here is the basic structure of Social Security: that is, a retirement plan that has some linkage from wage contributions to benefits and that offers an inflation-adjusted lifetime stream of payments. The program was intended from the start as a basic building block for retirement, with the idea that people would have other forms of retirement savings. But a certain number of Republicans want to turn the program into a private-sector retirement scheme, where people invest their own funds as they please. Meanwhile, a certain number of Democrats want to make the program much more redistributive from those with high incomes to those with lower incomes, which would mean a higher degree of separation between what is paid into the program and what is received.

But trying to transform Social Security into something else, so that its baseline function is diminished in pursuit of other goals, is certainly complex, and probably misguided. In comparison, fixing Social Security as it stands is fairly straightforward. If you aren't wild about elements of the Bipartisan Policy Commission suggestions, the specifics can certainly be tweaked. But the kinds of proposals described here have the great advantage that they don't rely on waving any magic wands. They don't claim that Social Security can be fixed by eliminating waste, fraud, and abuse, or by an unexpected surge of economic or stock market growth. The proposals just face the tradeoffs squarely, and suggest one way to proceed.