Here's Greenspan on what the budget projections looked like at that time:

"The most recent projections from the OMB indicate that, if current policies remain in place, the total unified surplus will reach $800 billion in fiscal year 2011, including an on-budget surplus of $500 billion. The CBO reportedly will be showing even larger surpluses. Moreover, the admittedly quite uncertain long-term budget exercises released by the CBO last October maintain an implicit on-budget surplus under baseline assumptions well past 2030 despite the budgetary pressures from the aging of the baby-boom generation, especially on the major health programs. The most recent projections, granted their tentativeness, nonetheless make clear that the highly desirable goal of paying off the federal debt is in reach before the end of the decade."But this good news of an unending future of budget surpluses did bring some issues to address. For example, when the federal government reached zero debt and stopped borrowing and became instead a holder of an ever-growing pile of financial assets, how would the decisions be made about which assets the government should hold?

"At zero debt, the continuing unified budget surpluses currently projected imply a major accumulation of private assets by the federal government. ... I believe, as I have noted in the past, that the federal government should eschew private asset accumulation because it would be exceptionally difficult to insulate the government's investment decisions from political pressures. Thus, over time, having the federal government hold significant amounts of private assets would risk sub-optimal performance by our capital markets, diminished economic efficiency, and lower overall standards of living than would be achieved otherwise."One possible option was to allow individual privatized accounts for Social Security, so that individuals rather than government would hold the growing mountain of these assets. In addition, the government would be wanting to pay off its long-term borrowing before the bonds were actually due--which might mean paying a premium to bondholders.

"But the more important issue is the potentially rising cost of retiring marketable Treasury debt. While shorter-term marketable securities could be allowed to run off as they mature, longer-term issues would have to be retired before maturity through debt buybacks. The magnitudes are large ... Some holders of long-term Treasury securities may be reluctant to give them up, especially those who highly value the risk-free status of those issues. Inducing such holders, including foreign holders, to willingly offer to sell their securities prior to maturity could require paying premiums that far exceed any realistic value of retiring the debt before maturity."The main emphasis was that the federal government needed to start thinking about an appropriate "glide path" to the brave new fiscal future of sustained budget surpluses, and the appropriate mixture of tax cuts and higher spending that was appropriate. Of course, there were a few paragraphs pointing out that this future also depended on avoiding "a major and prolonged economic contraction," as well as sustained rapid growth in productivity.

"The reason for caution, of course, rests on the tentativeness of our projections. What if, for example, the forces driving the surge in tax revenues in recent years begin to dissipate or reverse in ways that we do not now foresee? Indeed, we still do not have a full understanding of the exceptional strength in individual income tax receipts during the latter 1990s. ... Indeed, the current economic weakness may reveal a less favorable relationship between tax receipts, income, and asset prices than has been assumed in recent projections. Until we receive full detail on the distribution by income of individual tax liabilities for 1999, 2000, and perhaps 2001, we are making little more than informed guesses of certain key relationships between income and tax receipts.

"In the end, the outlook for federal budget surpluses rests fundamentally on expectations of longer-term trends in productivity, fashioned by judgments about the technologies that underlie these trends. Economists have long noted that the diffusion of technology starts slowly, accelerates, and then slows with maturity. But knowing where we now stand in that sequence is difficult--if not impossible--in real time. As the CBO and the OMB acknowledge, they have been cautious in their interpretation of recent productivity developments and in their assumptions going forward. That seems appropriate given the uncertainties that surround even these relatively moderate estimates for productivity growth. ... That said, as I have argued for some time, there is a distinct possibility that much of the development and diffusion of new technologies in the current wave of innovation still lies ahead, and we cannot rule out productivity growth rates greater than is assumed in the official budget projections."A few thoughts on all of this.

1) "It is very hard to predict, especially about the future." Economic projections depend on the underlying assumptions, and those are not written in stone.

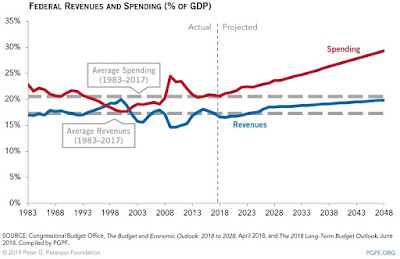

2) The good news is that through strong bipartisan consensus since 2001, the US government has decisively addresses the problems of paying off all the government debt and running overly large budget surpluses for decades into the future. Here are a few snapshots to remind us of what happened, and where we now seem to be headed, taken from the "Selected Charts on the Long-Term Fiscal Challenges of the United States" published by the Peter G. Peterson Foundation (January 2019, largely based on Congressional Budget Office data and estimates).

Here's federal spending and revenue expressed as a share of GDP. You can see that magic moment back in early 2001 when tax receipts were on the rise and spending was down. You can also see what happened when the dot-com boom ended in 2001: not only did taxes fall as the boom decreased, but tax cuts enacted both in response to the economic and stock market slowdown, but also in response to tax cuts that were intended both to help boost the economy out of the 2001 recession and also (I think) to reduce that pesky high tax take. Federal spending did remain below its historical average through the early 2000s, but then shot up when the Great Recession hit later in the decade.

Interestingly, both federal spending and revenues are pretty close to their historical share of GDP over the last 40 years or so at present.

Interestingly, both federal spending and revenues are pretty close to their historical share of GDP over the last 40 years or so at present.

This figure shows total federal debt held by the public (as opposed to debt held internally by other agencies of government). Again, that downward feint in the debt level in the the late 1990s is clearly visible. Greenspan and others were definitely seeing something in the data! But you can then see the steep rise in government debt after the Great Recession, and the projected rise (assuming current legislation is unchanged) into the future.

3) Greenspan's testimony is a reminder of how so many people thought and acted during the dot-com boom of the 1990s--that the surge of innovation and productivity growth at that time had a good chance of turning out to be permanent.

4) The experience since 2001 also points out that if the US government in its role as financial regulator and macroeconomic manager could at least minimize the size of the really bad recessions, like 2007-2009, it would have made a dramatic difference in the accumulated debt/GDP ratio. In addition, if there is a surge in productivity that lasts for some years, so many economic problems from budget deficits to wage growth become much more manageable. Without that surge of productivity growth, solutions to many of the same problems fall somewhere between "hard choices" and "politically impossible." There's no magic policy dial to turn up productivity growth. It's a matter of making the needed investments in human capital, physical capital and technology, in a context where there are incentives and rewards for those who seek out efficency and innovation.

4) The experience since 2001 also points out that if the US government in its role as financial regulator and macroeconomic manager could at least minimize the size of the really bad recessions, like 2007-2009, it would have made a dramatic difference in the accumulated debt/GDP ratio. In addition, if there is a surge in productivity that lasts for some years, so many economic problems from budget deficits to wage growth become much more manageable. Without that surge of productivity growth, solutions to many of the same problems fall somewhere between "hard choices" and "politically impossible." There's no magic policy dial to turn up productivity growth. It's a matter of making the needed investments in human capital, physical capital and technology, in a context where there are incentives and rewards for those who seek out efficency and innovation.