Here are a couple of nice readable overviews of the issues, both with references to a number of the key academic papers:

- Jeff Cockrell. "Does America have an antitrust problem?" in the Chicago Booth Review (Winter 2019/2020)

- Tim Sablik and Nicholas Trachter, "Are Markets Becoming Less Competitive?" in an Economic Brief from the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond (June 2019, EB 19-06)

Imagine a town somewhere that has three not-too-fancy but locally owned restaurants competing with each other: maybe a pasta place, a burger place, and a doughnut place. Then, national restaurant chains arrive in this town: maybe an Olive Garden, a Dunkin' Donuts, a Cheesecake Factory, a Red Robin, an Arby's, and a Subway. From a standpoint of competition in the local market, it seems clear that competition has increased. There used to be three restaurants, while now there are six. But from a national point of view, if this pattern happens in many towns, the big chain firms are expanding their market share and the restaurant industry will have greater concentration.

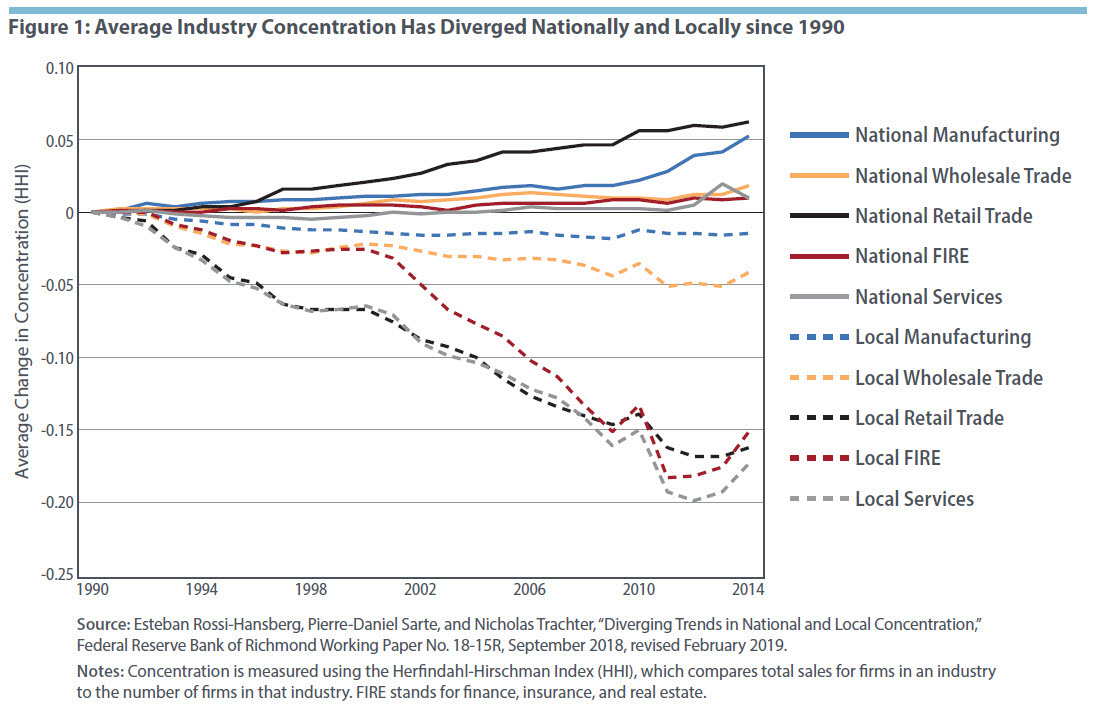

Sablik and Trachter offer some evidence that this kind of example--more local-level competition but less national-level competition--is pervasive. This figure shows that average industry concentration measured at the national level has been rising in recent decades, while measured at the local level it has been simultaneously falling.

The underlying lesson here is one of the classic problems in antitrust policy. If you say that "competition" is rising or falling, you have to define with some precision which market you are discussing.

Another possibility is the rise of "superstar" firms. The idea here is that certain firms in a range of industries have made large-scale investments in technology, along with the organizational capabilities to use that technology productively. As a results, these "superstar" firms are gaining market share, and thus leading to higher measures of industry concentration, while also earning higher profits. This pattern could explain a variety of other observed economic phenomena: for example, markups over cost of production would rise, because more firms would be producing with a technology that combined high fixed costs with low marginal costs; the labor share of income could decline, because leading firms are producing with a greater investment in technology and lower spending on labor; and the diffusion of productivity within a given industry would rise, as the "superstar" firms in an industry pull away from the rest.

However, notice that in this case rising concentration of industry is rising because of greater competition, not despite it. For a recent example of research on this "superstar" firms theme, see "The Fall of the Labor Share and the Rise of Superstar Firms," by David Autor, David Dorn, Lawrence F. Katz, Christina Patterson, and John Van Reenen (this is the October 2019 version of a paper forthcoming in the Quarterly Journal of Economics).

With examples like these in mind, Cockrell offers an overall judgement from Chad Syverson: “Concentration isn’t a good barometer of the extent of competition in the market,” says Chicago Booth’s Chad Syverson. “It’s not just a noisy barometer; we don’t even know what direction the needle is pointing. There are cases where, clearly, things happen in a market to make it more competitive, and concentration goes up.”

As an example, imagine rules that made made your personal data more portable. A step like this would probably encourage more competition in certain industries, because if your data moved with you, it would be easier to switch between phone companies, or banks, or health insurance providers. However, if it is easier to switch and competition goes up, a possible result is that the already-big providers grow even bigger, and concentration rises as well.

In short, when thinking about the extent of competition in a market, and how certain antitrust or regulatory policies might affect competition. it's reasonable to look at measures of industry concentration and how such measures might shift. But before one has a knee-jerk negative reaction to measures of higher industry concentration, one needs to be quite specific about how concentration is being measured: how a specific industry is defined, and whether the focus is local, regional, or national. One also needs to be aware that higher competition can lead to higher concentration for an extended period of time.