Jessie Romero tells the story in "Leaving LIBOR: The Fed has developed a new reference rate to replace the troubled LIBOR. Will banks make the switch?" which appears in Econ Focus from the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond (Third Quarter 2018).

LIBOR stands for the London Interbank Offered Rate. It's a benchmark interest rate, which means that when LIBOR goes up or down, the payments owed in a few hundred trillion dollars of contracts go up or down, too. The problem is that LIBOR has been calculates as a survey response to hypothetical question. Romero explains:

LIBOR is based on how much banks pay to borrow from one another. Each day, a panel of 20 international banks responds to the question, "At what rate could you borrow funds, were you to do so by asking for and then accepting interbank offers in a reasonable market size just prior to 11 a.m.?" The highest and lowest responses are excluded, and the remaining responses are averaged. Not every bank responds for every currency; 11 banks report for the franc, while 16 banks report for the dollar and the pound. For each of the five currencies, LIBOR is published for seven different maturities, ranging from overnight to 12 months. In total, 35 rates are published every applicable London business day.

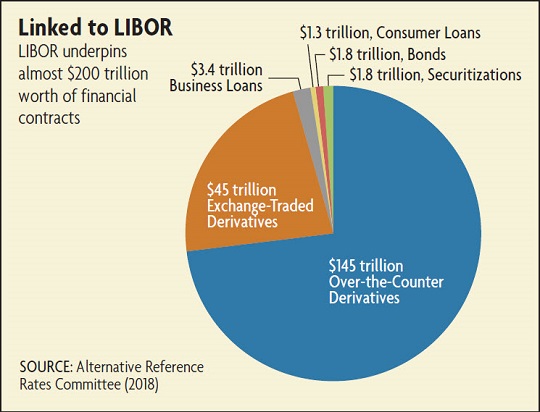

About 95 percent of the outstanding contracts based on LIBOR are for derivatives. (See chart below.) It's also used as a reference for other securities and for variable rate loans, such as private student loans and adjustable-rate mortgages (ARMs). In 2012, the Cleveland Fed calculated that about 80 percent of subprime ARMs were indexed to LIBOR, as well as about 45 percent of prime ARMs. Prior to the financial crisis, essentially all subprime ARMs were linked to LIBOR.

What happened in the LIBOR scandal was that some too-smart traders at Barclay's, JP Morgan Chase, and Citigroup figured out that if just a few of the people answering the LIBOR survey would slant their responses just a bit, this benchmark interest rate could be manipulated a tiny bit higher or lower. And any trader who knows where the benchmark is headed--even if the movement is a tiny one--is well-positioned to consistently make a lot of money. Romero writes:

As regulators investigated ... [b]eginning at least in 2003, banks had been submitting LIBOR reports that would benefit their trading positions. Rate submitters and traders at different banks and brokerages also conspired with each other to manipulate LIBOR, promising each other steaks, Champagne, and Ferraris (among other perks). Internal emails and instant messages revealed the scheme. As one trader wrote, "Sorry to be a pain but just to remind you the importance of a low fixing for us today." Another wondered "if it suits you guys on hiking up 1bp on the 6mth Libor in JPY [one basis point on the six- month LIBOR in Japanese yen] ... it will help our position tremendously." At least 11 financial institutions faced fines and criminal charges from multiple international agencies, including the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) and the Justice Department in the United States. Separately, in 2014 the FDIC sued 16 global banks for manipulating LIBOR, alleging that their actions had caused "substantial losses" for nearly 40 banks that went bankrupt during the financial crisis.Although LIBOR has continued under stricter management, it seems clear that it was a bad idea to have a benchmark interest rate determined by answers to a survey. Instead, the challenge was to choose an interest rate for very safe borrowing--remember, LIBOR was banks borrowing from each other for very short terms, including overnight--but determined in a market that had lots of liquidity and volume.

Various groups of brainiacs tackles the problem. As one example from a few years ago in 2015, Darrell Duffie and Jeremy C. Stein surveyed the possible options in "Reforming LIBOR and Other Financial Market Benchmarks" published in the Journal of Economic Perspectives (29 (2): 191-212). Eventually an Alternative Reference Rates Committee was convened by the Federal Reserve, with representation from both government agencies and the private sector, and it published its recommendation in a March 2018 report.

Bottom line: It recommends using the SOFR as the preferred benchmark interest rate, which stands for Secured Overnight Financing Rate. It refers to the cost of borrowing which is extremely safe, because the borrowing is only overnight, and there are Treasury securities used as collateral for rthe borrowing. The SOFR rate is based on a market with about $800 billion in daily transactions, and this kind of overnight borrowing doesn't just include banks, but covers a wider range of financial institutions. The New York Fed publishes the SOFR rate every morning at 8 eastern time.

But perhaps the best reason for using SOFR is that an agreed-upon benchmark interest rate is needed, and LIBOR is going away. As Romero reports, banks have been trying to duck out of answering the LIBOR survey for a few years now, and have continued to participate only because of threats from regulators. After all, with hundreds of trillions of financial contracts using LIBOR, it was important for the stability of global financial markets that the reference rate didn't become volatile or vanish altogether. But by around 2021, the financial regulators are ready to let LIBOR die. New financial contracts are often now being written with SOFR, instead.

For most of us, the shift from LIBOR to SOFR doesn't affect our daily lives. But when you are discussing a risk-free interest rate, or a benchmark interest rate for a contract or mortgage with adjustable rates, you are soon going to stop hearing about LIBOR. For practical purposes, just remember that SOFR serves the same benchmark interest rate function.