Economics of Ageing Populations, a free ebook with 20 short essays summarizing a range of research on the topic (October 2019, VoxEU.org, registration required). Then Bloom contributed the lead article, "Population 2020: Demographics can be a potent driver of the pace and process of economic development," in the most recent issue of Finance & Development (March 2020, pp. 4-9). At the moment, of course, a primary concern is that older people may be more vulnerable to the spread of COVID-19. But more broadly, a shift in the distribution of ages across society will have broad consequences for social institutions and government policies.

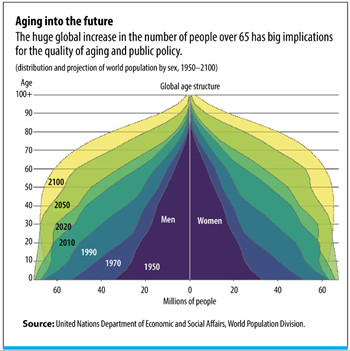

Here's a figure from Andrew Scott, in his F&D essay "The Long, Good Life," which gives as sense of the shift. The horizontal axis of the figure shows the expansion of population over time. The vertical axis shows the shift in aging. Thus, the shaded area for 1950 is narrower (fewer people) and more pointed near the top (fewer older people). The time periods that follow get wider (more people) and also develop "shoulders," representing a population where more people stay older for longer.

Bloom explains the underlying patterns, including the "demographic transition" and the graying population, in his F&D essay:

In many developing economies, population growth has been associated with a phenomenon known as the “demographic transition”—the movement from high to low death rates followed by a corresponding movement in birth rates.

For most of human history, the average person lived about 30 years. But between 1950 and 2020, life expectancy increased from 46 to 73 years, and it is projected to increase by another four years by 2050. Moreover, by 2050, life expectancy is projected to exceed 80 years in at least 91 countries and territories that will then be home to 39 percent of the world's population. ... Cross-country convergence in life expectancy continues to be strong. For example, the life expectancy gap between Africa and North America was 32 years in 1950 and 24 years in 2000; it is 16 years today. ...

In the 1950s and 1960s, the average woman had roughly five children over the course of her childbearing years. Today, the average woman has somewhat fewer than 2.5 children. This presumably reflects the growing cost of child-rearing (including opportunity cost, as reflected mainly in women’s wages), increased access to effective contraception, and perhaps also growing income insecurity. ... Between 1970 and 2020, the fertility rate declined in every country in the world. ...

If the population’s age structure is sufficiently weighted toward those in prime childbearing years, even a fertility rate of 2.1 can translate into positive population growth in the short and medium term, because low fertility per woman is more than offset by the number of women having children. This feature of population dynamics is known as population momentum and helps explain (along with migration) why the populations of 69 countries and territories are currently growing even though their fertility rates are below 2.1.

The result of this demographic transition is a population with a rising number and share of elderly. Bloom writes:

Population aging is the dominant demographic trend of the twenty-first century—a reflection of increasing longevity, declining fertility, and the progression of large cohorts to older ages. Never before have such large numbers of people reached ages 65+ (the conventional old-age threshold). We expect to add 1 billion older individuals in the next three to four decades, atop the more than 700 million older people we have today. Among the older population, the group aged 85+ is growing especially fast and is projected to surpass half a billion in the next 80 years. This trend is significant because the needs and capacities of the 85+ crowd tend to differ significantly from those of 65-to-84-year-olds.

Although every country in the world will experience population aging, differences in the progression of this phenomenon will be considerable. Japan is currently the world leader, with 28 percent of its population 65 and over, triple the world average. By 2050, 29 countries and territories will have larger elder shares than Japan has today. In fact, the Republic of Korea’s elder share will eventually overtake Japan’s, reaching the historically unprecedented level of 38.1 percent. Japan’s median age (48.4) is also currently the highest of any country and more than twice that of Africa (19.7). But by 2050, Korea (median age 56.5 in 2050) is also expected to overtake Japan on that metric (54.7).

Three decades ago,the world was populated by more than three times as many adolescents and young adults (15- to 24-year-olds) as older people. Three decades from now, those age groups will be roughly on par.

I won't try here to summarize all the discussions in the F&D and the ebook. Instead, I'll just list the tables of contents below. But here are a few thoughts:

- Consider your mental picture of an extended family gathering. Maybe it's a holiday with grandparents, parents, and children. Maybe it's a family reunion with a larger group of aunts, uncles, and cousins. Now in thinking about that family reunion, think about it being much more common to including five generations: that is, from great-great-grandparents down to children. In addition, think about there being fewer people in each generation, as a result of fewer children. The "family tree" is going to look taller and skinnier.

- As we shift from (in Bloom's calculation) a world where there are three times as many young people as elderly to a world where those populations are equal, public institutions will also shift to meet the needs of the elderly. The design of parks, libraries, public transit, city streets, shopping malls, and much more will evolve to reflect more emphasis on the needs and desires of the elderly. On the other side, schools and education will be a shrinking part of what government does.

- Caring for the elderly who need a range of support from an occasional in-home visit to living in a full-care institution is going to be a growth industry, needing both additional workers and technological innovations. This will be especially true as the number of extremely elderly people rises--often defined now as those over 85, but in the future perhaps defined as those over 100. In addition, the elderly will have had fewer children, and thus are less likely to have access to within-family support.

- It will be important for the workplace to shift in ways that provide jobs with the flexibility and interest to appeal to at least the "young elderly," who might otherwise just choose to retire completely.

- Government spending on programs to support the elderly, including pensions and health care, are going to rise dramatically in size.

- All over the world, including the US, it's time to start phasing back the age of retirement at which people become eligible for pension plans. Exactly how that is done, and what kind of flexibility is available for retiring earlier or later, is open for discussion. But an expectation that retirement ages will in general be later is a fundamental step in making government-provided social security or pensions sustainable in the long run.

- Older people tend to save less, as they draw down their retirement accounts, but also to look for less risky and volatile investments (more bonds, less stock market).

- Keeping older people healthy and functioning later in life will be an urgent need, both for the people themselves and also to reduce the need for outside support.

Following Bloom's lead-off essay, other essays on this topic in the March 2020 F&D include:

- Andrew Scott, "The Long, Good Life: Longer, more productive lives will mean big changes to the old rules of aging:

- Poh Lin Tan, "Reversing Demographic Decline: Singapore’s experience in trying to raise its fertility rate offers lessons for other countries "

- Lawrence H. Summers, "Accepting the reality of secular stagnation: New approaches are needed to deal with sluggish growth"

- Gee Hee Hong and Todd Schneider, "Japan's Shrinkonomics: Japan is the world’s policy laboratory for dealing with an aging, shrinking population"

- Maria Petrakis, "Eastern Europe’s Exodus: In Europe’s newest states, emigration compounds the problem of aging populations"

- Giovanni Peri,: Immigrant Swan Song: Immigration can solve the demographic dilemma— but not without the right policies""

- David Amaglobeli, Era Dabla-Norris, and Vitor Gaspar, "Getting Older but Not Poorer: As societies age worldwide, pensions and public policies must adapt"

In the e-book, the Table of Contents is:

1) "The what, so what, and now what of population ageing," by David E. Bloom

Part I: Implications of Population Ageing: The 'So What'

2) "Who will care for all the old people?" by Finn Kydland and Nick Pretnar

3) "Employment and the health burden on informal caregivers of the elderly," by Jan M. Bauer and Alfonso Sousa-Poza

4) "Ageing in global perspective," by Laurence J. Kotlikoff

5) "What do older workers want?" by Nicole Maestas and Michael Jetsupphasuk

6) "The flip side of "live long and prosper": Noncommunicable diseases in the OECD and their macroeconomic impact," by David E. Bloom, Simiao Chen, Michael Kuhn and Klaus Prettner

7) "Macroeconomic effects of ageing and healthcare policy in the United States," by Juan Carlos Conesa, Timothy J. Kehoe, Vegard M. Nygaard and Gajendran Raveendranathan

8) "Global demographic changes and international capital flows," by Weifeng Liu and Warwick J. McKibbin

9) "Ageing into risk aversion? Implications of population ageing for the willingness to take risks," by Margaret A. McConnell and Uwe Sunde

10) "Life cycle origins of pre-retirement financial status: Insights from birth cohort data," by

Mark McGovern

11) "A longevity dividend versus an ageing society," by Andrew Scott

2) "Who will care for all the old people?" by Finn Kydland and Nick Pretnar

3) "Employment and the health burden on informal caregivers of the elderly," by Jan M. Bauer and Alfonso Sousa-Poza

4) "Ageing in global perspective," by Laurence J. Kotlikoff

5) "What do older workers want?" by Nicole Maestas and Michael Jetsupphasuk

6) "The flip side of "live long and prosper": Noncommunicable diseases in the OECD and their macroeconomic impact," by David E. Bloom, Simiao Chen, Michael Kuhn and Klaus Prettner

7) "Macroeconomic effects of ageing and healthcare policy in the United States," by Juan Carlos Conesa, Timothy J. Kehoe, Vegard M. Nygaard and Gajendran Raveendranathan

8) "Global demographic changes and international capital flows," by Weifeng Liu and Warwick J. McKibbin

9) "Ageing into risk aversion? Implications of population ageing for the willingness to take risks," by Margaret A. McConnell and Uwe Sunde

10) "Life cycle origins of pre-retirement financial status: Insights from birth cohort data," by

Mark McGovern

11) "A longevity dividend versus an ageing society," by Andrew Scott

Part II: Solutions and Policies: The 'Now What'

12) "Understanding 'value for money' in healthy ageing," by Karen Eggleston

13) "Healthy population ageing depends on investment in early childhood learning and development," by Elizabeth Geelhoed, Phoebe George, Kim Clark and Kenneth Strahan

14) "Financing health services for the Indian elderly: Aayushman Bharat and beyond," by Ajay Mahal and Sanjay K. Mohanty

15) "Cutting Medicare beneficiaries in on savings from managed healthcare in Medicare," by Thomas G. McGuire

16) "Macroeconomics and policies in ageing societies,"by Andrew Mason, Sang-Hyop Lee, Ronald Lee and Gretchen Donehower

17) "Population ageing and tax system efficiency," by John Laitner and Dan Silverman

18) "Means-tested public pensions: Designs and impact for an ageing demographic," by George Kudrna and John Piggott

19) "Pension reform in Europe," by Axel Börsch-Supan

20) "Happiness at old ages: How to promote health and reduce the societal costs of ageing," by Maddalena Ferranna