Most high-income countries in the world have government-required provision of sick pay. Researchers at the World Policy Analysis Center at UCLA compiled data in a 2018 report "Paid Leave for Personal Illness: A Detailed Look at Approaches Across OECD Countries." They write that of 34 OECD countries, only the US and Korea do not have a guarantee of paid leave for personal illness. The details of implementation vary across countries, of course. For example, two of these countries make employers solely responsible for paying for sick leave, nine countries have government solely responsible, and 21 have a mixture of the two. In the mixed systems, a common pattern is that employers pay for the first few weeks of sick leave, and then government takes over after that up to some limit like three or six months. A common pattern in these countries is that sick leave is 80% of regular pay.

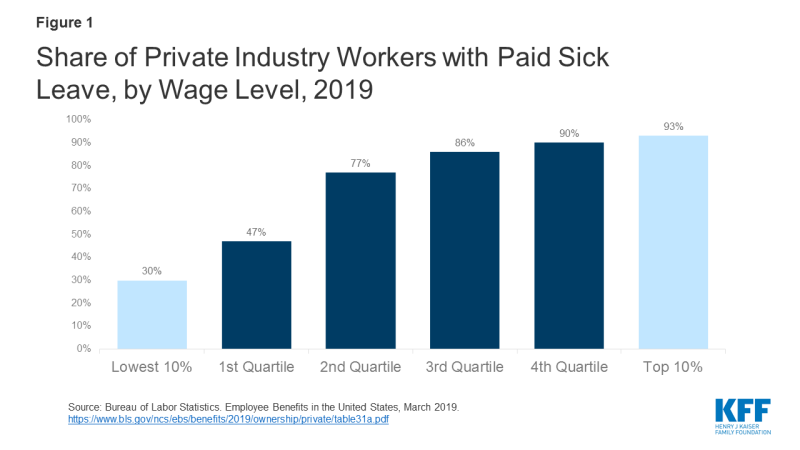

In the US, sick leave is much less likely in lower-paying jobs. Here's a figure showing the pattern from the Kaiser Family Foundation:

Efforts to have federal sick pay rule in the US have gone nowhere. However, starting with San Franciso in 2007, a number of state and local governments have passed such rules in the last few years. Twelve states now have such laws, and a couple of dozen more cities, including New York City, Chicago, Philadelphia, Washington DC, Seattle, and Portland. The typical pattern for these laws is that all employees earn one hour of paid sick leave for every 30 to 40 hours worked. Of course, the idea behind this design is that a worker can't take a job and then immediately take paid sick leave, but a worker will accumulate roughly a day of paid sick leave for every 8 weeks worked. For a detailed and updated "Interactive Overview of Paid Sick Time Laws in the United States," see the A Better Balance website.

What are the effects of these laws? Stefan Pichler and Nicolas R. Ziebarth have written "Labor Market Effects of U.S. Sick Pay Mandates," forthcoming in the Spring 2020 issue of the Journal of Human Resources (55:2, pp. 611–659). They look at employment and wage data over a time frame from 2001 to 2016 for nine cities and four states that have enacted sick pay rules. They create what is called a "synthetic control group," which is a set of cities and states that historically have followed the same patterns of employment and wages, but did not adopt a sick pay rule. Then, they can see whether adopting sick pay causes a change in employment and wages compared to this control group. They find no evidence of such a change.

In a follow-up study, Johanna Catherine Maclean, Stefan Pichler, and Nicolas R. Ziebarth have published a working paper, "Mandated Sick Pay: Coverage, Utilization, and Welfare Effects" (March 2020, NBER Working Paper #26832, not freely available, but readers may have access through their institutiosn). This study focuses on state-level sick-pay mandates, with data from 2009-2017. During this time, states are adopting sick pay mandates at different times. Thus, for these states and in comparison with other states, one can look for how patterns of sick leave coverage change when sick-pay mandates are adopted. They find:

Within the first two years following mandate adoption, the probability that an employee has access to paid sick leave increases by 18 percentage points from a base coverage rate of 66%. The increase in coverage persists for at least four years without rising further. Over all post-mandate periods covered by this paper, we find a 13 percentage point higher coverage rate attributable to state mandates. As a result of the increased access to paid sick leave, employees take more sick days ... newly covered employees take two additional sick days per year. Employer sick leave costs also increase, but effect sizes are modest. On average, the increase amounts to 2.7 cents per hour worked ... Further, we find little evidence that sick pay mandates crowd-out non-mandated benefits such as paid vacation or holidays. Likewise, we find no evidence that employers curtail the provision of group policies such as health, dental, or disability insurance.These studies are focused on labor market issues, and do not take public health effects into account. However, in a different working paper, Stefan Pichler, Katherine Wen, Nicolas R. Ziebarth study

"Positive Health Externalities of Mandating Paid Sick Leave" (February 2020). Looking at state-level data, they find that in the first year after a state enacts sick pay, rates of doctor-certified influenza-like illness fell by about 11%.

This offered broad confirmation of results from an earlier study by Stefan Pichler and Nicolas R. Ziebarth, "The pros and cons of sick pay schemes: Testing for contagious presenteeism and noncontagious absenteeism behavior" (Journal of Public Economics, December 2017, pp. 14-33). Looking at Google Flu data, they found that when U.S. employees gain access to paid sick leave, the general flu rate in the population decreases significantly, which suggests the possibility of less transmission of flu at work.

They also look at sick pay outcomes in Germany, a country with generous sick pay provisions. However, when Germany legislative changes allowed some flexibility to reduce sick pay from 100% of previous salary to 80%, the result was a large drop in more nebulous claims sickness claims like "back pain" but little drop for sickness claims related to infectious illnesses. This pattern suggests a plausible tradeoff: very generous sick pay can lead to workers taking time off for reasons not related to public health, but as sick pay becomes less generous, it will also lead to "contagious presenteeism" where contagious workers become more likely to show up at the job.

(In passing, I was also struck by this historical comment about Germany sick pay in the Pichler and Ziebarth 2017 paper: "Historically, paid sick leave was actually one of the first social insurance pillars worldwide; this policy was included in the first federal health insurance legislation. Under Otto van Bismarck, the Sickness Insurance Law of 1883 introduced social health insurance in Germany, which included 13 weeks of paid sick leave along with coverage for medical bills. The costs associated with paid sick leave initially made up more than half of all program costs, given the limited availability of (expensive) medical treatments in the nineteenth century ...")

Some US companies are now discovering that sick pay may matter to their business: for example,

"Amazon announces up to 2 weeks of paid sick leave for all workers and a 'relief fund' for delivery drivers amid coronavirus outbreak." But the kinds of sick pay laws that have been gradually spreading through certain states and cities are partial and incomplete. The novel coronovirus outbreak suggests that a national sick pay policy--probably with employers responsible for the first weeks and then government serving as a back-up--is an issue with broad public health consequences, not just an argument over whether government should require companies to provide certain benefits. Sitting here in March 2020, it would have been nice to have a national sick-pay policy in place a few years ago, as a way of reducing the spread of coronavirus and cushioning the loss of income for those who become sick. But it's not too early to start prepping for the next pandemic.