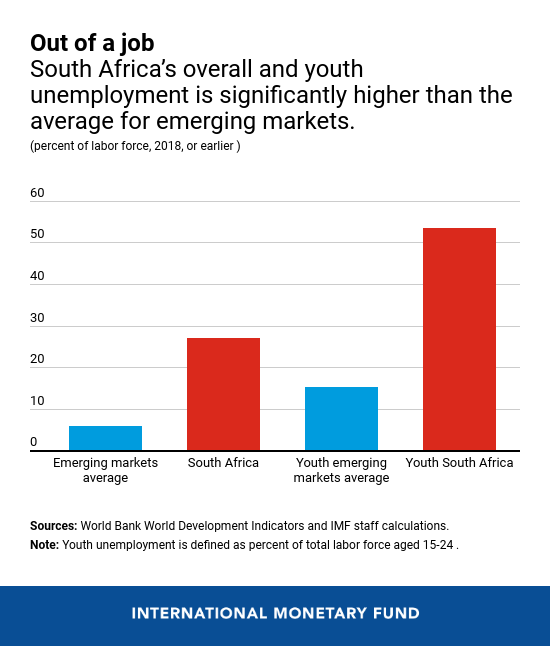

Other IMF stats show that overall unemployment is 25% and youth unemployment exceeds 50%. A combination of high-income cities like Johannesburg and Pretoria and low-income urban slums and rural areas have also combined to make South Africa one of countries with highest levels of income inequality.

The IMF just completed an evaluation of South Africa's economic situation a few weeks ago. Also, in August 2019, South Africa's Treasury department published a list of suggested reforms. What are some themes that emerge about what has gone wrong and what needs to be done?

1) Many of South Africa's state-owned enterprises (SOEs) seem to be in disastrous shape, and the biggest disaster is ESKOM, the electricity public utility. The IMF writes:

Most SOEs face elevated costs arising from bloated wage bills and costly procurement. Cost increases have outstripped tariff increases and cuts in capital expenditure, and debt service burden has risen, keeping SOEs net cash flows negative. Eskom is by far the largest SOE and its position is particularly critical, with an operational balance insufficient to service its high debt—around 10 percent of GDP. ... Corruption, delays in debt-financed investments, and expensive procurement have generated cost-overruns and left Eskom reliant on outdated plants vulnerable to breakdowns (the average age of the fleet is 37 years).

Other especially problematic state-owned enterprises are South African Airways and the passenger railway company PRASA.

2) In substantial part because of subsidies to the state-owned enterprises, South Africa's government is already running large fiscal deficits--which of course makes it difficult to focus resources on social spending. The IMF writes:

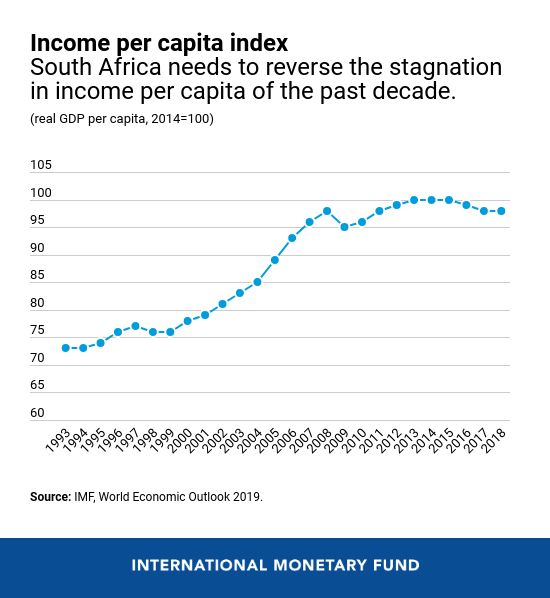

In the early and mid-2000s, annual output growth averaged about 4 percent, fiscal deficits turned to small surpluses, and public debt declined to 27 percent of GDP. By contrast, starting in the late-2000s, private investment’s contribution to growth fell considerably, and total factor productivity (TFP) growth became negative, dampening growth to slightly above 1 percent. Following the countercyclical easing at the time of the global financial crisis, fiscal deficits have remained wide at around 4½ percent of GDP, more than doubling public debt to close to 60 percent of GDP.

IMF projections are for the annual deficits to get higher, in substantial part because of promised subsidies to the state-owned enterprises, but also for paying interest on past borrowing--much of which is paid to international investors outside South Africa.

3) Product markets in South Africa strongly favor large incumbent firms, and choke off new competitors. The IMF again:

Several economic sectors, including manufacturing and banking, are dominated by a handful of big players with significant market power. High concentration has inhibited the emergence of smaller firms, which are powerful job creators in other EMs [emerging markets]. SMEs [small and medium enterprises] have shrunk in importance relative to large firms in the past decade. Staff analysis suggests that rising input costs and markups are associated with declining economic growth. This is clearly the case of large SOEs that pass-on high costs to businesses, thus sustaining elevated priceOne striking comparison looks at "mark-ups" across countries--that is, how much are the prices that countries charge above marginal cost of production? Here's a study that looks at the change in mark-ups over time, compared to the rise in marginal costs.

levels and reducing the economy’s competitiveness. Firms subject to restrictive procurement and labor regulations also suffer from high costs and low productivity. A distributional analysis suggests that the poor are more affected as they face both fewer employment opportunities and higher prices.

Here's another figure looking at concentration in the retail industry, which is often an industry that can be friendly to new entrants. South African retail is far more concentrated than the comparison countries.

4) South Africa is experiencing a labor market mismatch, where much of the job growth is in higher-skilled jobs and much of the unemployment is among lower-skilled workers. Moreover, requiring that state-owned enterprises pay high wages means that these firms try not to hire lower-skilled workers. As the IMF writes:

South Africa has a higher level of unemployment and lower labor force participation than both regional and emerging economies. With skill mismatches and economic growth tilted toward the most sophisticated sectors (finance, information technology, and specialized business services), the bulk of job creation benefits high-skilled workers as opposed to low-skilled workers and labor-intensive industries including agriculture, tourism, and manufacturing. Further, labor cost increases exceed productivity improvements—largely a reflection of the centralized wage bargaining that transmits labor cost increases to the rest of the economy—systematically keeping demand for labor (including for new entrants) significantly below employment needs. Firm closures further worsen the dynamics. ... Regulatory constraints that inhibit firms’ ability to hire on a need basis limit employment opportunity, particularly for the inexperienced and the youth. To justify payment of centrally bargained wage levels, firms prefer to hire skilled and experienced workers, who represent a small percentage of the population.This is why one of the main recommendations from the report of South Africa's Treasury focuses on "prioritizing labour-intensive growth in sectors such as agriculture and services, including tourism."

5) In the long run, a key element for South Africa will be its education system and other methods of getting future employees the skills they need. South Africa's education system is not performing well. From the IMF, here's a figure showing spending on education on the horizontal axis, and performance on the international PISA tests on the vertical axis. South Africa's performance lags far behind other countries with a similar level of spending.

The South African Treasury, before starting its discussion of reforming state-owned enterprises and all the rise, first emphasizes the importance of education in its report:

However, any attempt to raise South Africa’s potential growth rate must include progress on the fundamental building blocks of long-run sustainable growth. First, there must be an emphasis on improving educational outcomes throughout the educational life-cycle ... The South African education system, which other countries have used to promote equality of opportunity, perpetuates inherited socio-economic disadvantage: if your parents are poor, the chances of your being poor are about 90 per cent (Finn et al. 2016). The lack of a transformative education system is a key factor in this persistence. Our educational outcomes are poor, even when compared to other less well-resourced countries in the region. This is a major driver of intergenerational inequality and inhibits the inclusivity of growth and global competitiveness. Since the highest return to human capital investments are associated with the earliest interventions, an educational life-cycle approach must include a strong emphasis on early childhood development, which has demonstrated the ability to: (i) improve long-term health outcomes (Campbell et al. 2014); (ii) boost earnings by as much as 25 per cent (Gertler et al. 2014); and (iii) generate a rate of return on investment of 7 to 10 per cent through better outcomes in education, health, and productivity (Heckman et al. 2010). Evidence of inadequate

teacher content knowledge (see Venkat and Spaull 2015) and significant reading deficits in primary schools (see Spaull and Kotze 2015) points to the need for a comprehensive reading plan for primary school learners drawing on successful experiences such as the provision of reader anthologies.

Second, we need to continue to implement youth employment interventions, including training opportunities that remove barriers to entering the labour market and apprenticeships based on close cooperation between technical, vocational, and other training institutions and the private sector to ensure that training needs are demand-driven (Bhorat et al. 2014). Investing in the capabilities and educational and health outcomes of young people is unlikely to yield a dividend unless the youth are absorbed by labour markets (Mlatsheni 2014).6) A separate report from the IMF also added a discussion of the problem of crime in South Africa. For illustration, here's the homicide rate in South Africa, which has dropped a bit since 2000 but remains very high.

Surveys of business in South Africa see the crime rate as one of the biggest problems.

International comparisons of businesses also suggest that crime is a particular problem in South Africa.

Overall, the in-depth discussion of policy steps by South Africa's Treasury sums up this way:

These growth reforms are organized according to the following themes: (i) modernizing network industries; (ii) lowering barriers to entry and addressing distorted patterns of ownership through increased competition and small business growth; (iii) prioritizing labour-intensive growth in sectors such as agriculture and services, including tourism; (iv) implementing focused and flexible industrial and trade policy; and (v) promoting export competitiveness and harnessing regional growth opportunities. We estimate the economy-wide impact of the proposed interventions over time based on when they can realistically be implemented, and find they can raise potential growth by 2–3 percentage points and create over one million job opportunities.There used to be a hope that South Africa's economy could provide provide both an example and an engine for lifting standards of living across sub-Saharan Africa. Back around 1995, for example, South Africa had about 7% of the total population of sub-Saharan Africa, but the GDP of South Africa was about one-third of total GDP for the region. By 2018, however South Africa had about 5% of the population of sub-Saharan Africa, but 21% of the total GDP of sub-Saharan Africa. The blunt truth seems to be that South Africa's government has not delivered in the last decade on many important outcomes: not in education and training, running state-owned enterprises, providing a climate for new businesses to start, not in reducing inequality, getting crime under control, or keeping government debt manageable.