There is no official data on "entrepreneurship." Thus, the data on the size and age of firms needs to be treated with care. For example, a big company opening up one more store certainly isn't what most of us mean by an "entrepreneur." Nor is a new company formed because of a merger or a spin-off from existing companies. In addition, not all small firms are what we commonly think of as entrepreneurs. For example, many small family-run companies have been around for a substantial period of time, and don't really expect to experience large-scale growth. Thus, Decker, Haltiwanger, Jarmin and Miranda focus on the data on the age of firms, and they strip out new firms created out of old ones. When the data is sliced in this way, the note that business startup rate is down (citations omitted).

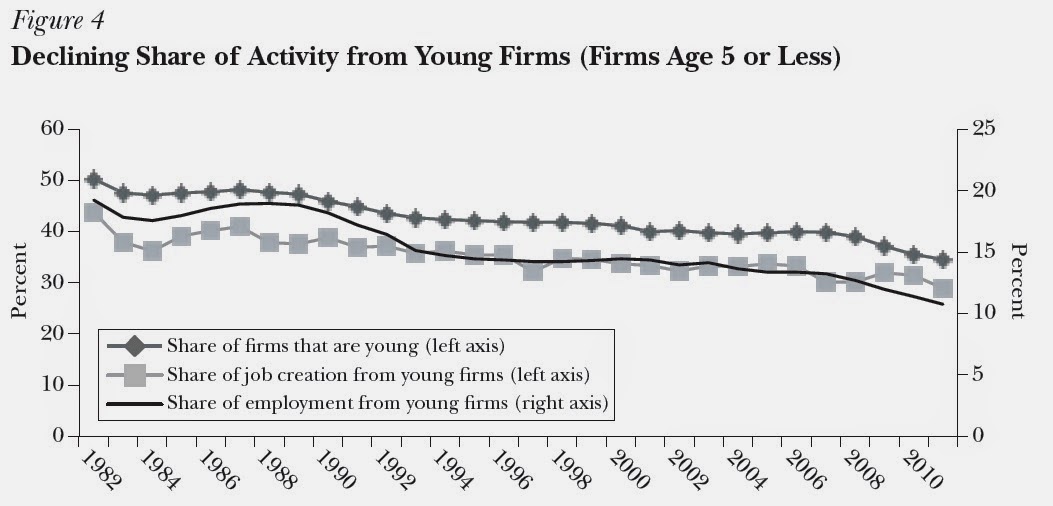

"The firm startup rate is measured by the number of new firms divided by the total number of firms. Our calculations based on the Business Dynamic Statistics data show that the annual startup rate declined from an average of 12.0 percent in the late 1980s to an average of 10.6 percent just before the Great Recession, when it plummeted below 8 percent. We also find that the startup rate has declined in all major sectors. We note, however, that in high-tech sectors, the startup rate only began to decline in the post 2000 period. Meanwhile, the average size of startups, as measured by employment, has either remained approximately the same over this time period as measured by the CensusAs a result, young firms have been playing a smaller role in the U.S. economy over time. The line with diamonds shows the share of firms that are less than five years old in the U.S. economy, and the decline since the 1980s. The line with the squares shows the share of job creation from young firms, and its decline since the 1980s. The solid lines shows the share of employment in young firms, and its decline since the 1980s.

Bureau’s Business Dynamics Statistics data or has declined as measured by the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Business Employment Dynamics. Either way, the lower startup rate is not being offset by a larger size of startup firms."

Two of the biggest problems for the U.S. economy in recent years are a slow pace of job creation and a slow pace of productivity growth. Entrepreneurship is closely linked to both. New firms and young firms as a group have traditionally played a major role in the creation of new jobs. The authors point to an "up-or-out" dynamic where many new firms fail, but those who succeed have a lasting effect.

"For new firms (that is, those with age equal to zero in the Business Dynamics Statistics) ... their net job creation is also 2.9 million jobs per year. Over these 30 years [from 1980 to 2010], average net job creation in the entire US private sector was approximately 1.4 million jobs per year. The implication is that cohorts of firms aged one year or older typically exhibit net job declines. ... For any given cohort, jobs lost due to the high failure rate of young firms are almost offset by the growth of the surviving firms. Five years after the entry of a typical cohort, total employment is about 80 percent of the original employment contribution of the cohort—in spite of losing about 50 percent of the original employment to business exits."Moreover, young firms are not only more likely to have high productivity than existing firms, they also create competitive pressure on existing firms to keep measuring up.

Ian Hathaway and Robert Litan present some complementary evidence on the U.S. decline in entrepreneurship in "The Other Aging of America: The Increasing Dominance of Older Firms," a discussion paper just released by the Brookings Institution. Here's one figure showing that older firms are a rising share of US firms in recent decades, while younger firms are a smaller share of firms. The second figure shows that a greater share of US employment is now at older firms, rather than at younger ones.

The public policy issues of how to increase the rate of business start-ups--which needs to involve thinking about how a wide variety of government rules and laws on hiring, production, and land use can create unnecessarily high hurdles for entrepreneurs--needs to wait for another day. Decker, Haltiwanger, Jarmin, and Miranda point out that the start-up rate is falling, and Hathaway and Litan offer a figure showing that it's a lack of start-ups, not a greater chance of failure, which is whittling down the role of young firms in the U.S. economy.

(Full disclosure: I've been Managing Editor of the JEP since the first issue in 1987. All JEP articles back to the first issue are freely available on-line, compliments of the American Economic Association.)