[In honor of pumpkin pie, I'm repeating this blog from a year ago.]

The facts are clear enough. As the US Department of Agriculture points out (citations omitted):

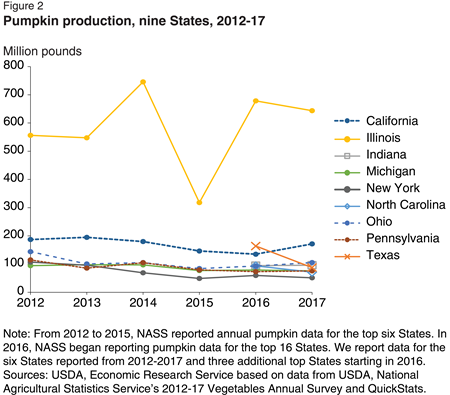

In 2016, farmers in the top 16 pumpkin-producing States harvested 1.1 billion pounds of pumpkins, implying about 1.4 billion pounds harvested altogether in the United States. Production increased 45 percent from 2015 largely due to a rebound in Illinois production. Illinois production, though highly variable, is six times the average of the other top eight pumpkin-producing States (Figure 2).

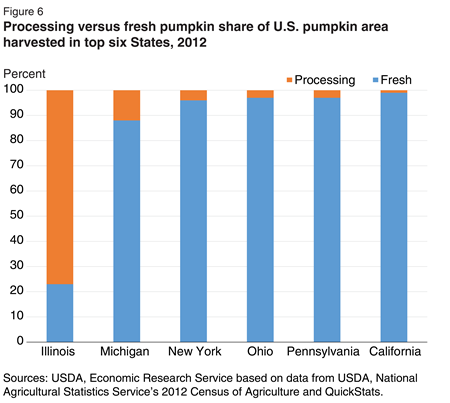

Not only does Illinois produce more pumpkins, but a much larger share of pumpkins from this state end up being processed, rather than used fresh. The USDA reports:

It's not really the entire state of Illinois, either, but mainly an area right around Peoria. The University of Illinois extension service writes: "Eighty percent of all the pumpkins produced commercially in the

U.S. are produced within a 90-mile radius of Peoria, Illinois. Most of those pumpkins are grown for processing into canned pumpkins. Ninety-five percent of the pumpkins processed in the United States are grown in Illinois. Morton, Illinois just 10 miles southeast of Peoria calls itself the `Pumpkin Capital of the World.'"

Why does this area have such dominance? Weather and soil are part of the advantage, but it seems unlikely that the area around Peoria is dramatically distinctive for those reasons alone. This also seems to be a case where an area got a head-start in a certain industry, established economies of scale and expertise, and has thus continued to keep a lead. The Illinois Farm Bureau writes: "Illinois earns the top rank for several reasons. Pumpkins grow well in its climate and in certain soil types. And in the 1920s, a pumpkin processing industry was established in Illinois, Babadoost [a professor at the University of Illinois] says. Decades of experience and dedicated research help Illinois maintain its edge in pumpkin production." According to one report, Libby’s Pumpkin is "the supplier of more than 85 percent of the world’s canned pumpkin."

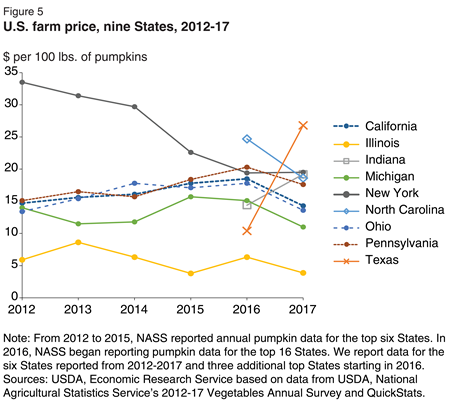

The farm price of pumpkins varies considerably across states, which suggests that it is costly to ship substantial quantities of pumpkin across moderate distances. For example, the price of pumpkins is lowest in Illinois, where supply is highest, and the Illinois price is consistently below the price for other nearby Midwestern states. This pattern suggests that the processing plants for pumpkins are most cost-effective when located near the actual production.

Finally, although my knowledge of recipes for pumpkin is considerably more extensive than my knowledge of supply chain for processed pumpkin, it seems plausible that demand for pumpkin is neither the most lucrative of farm products, nor is it growing quickly, so it hasn't been worthwhile for potential competitors in the processed pumpkin market to try to establish an alternative pumpkin-producing hub somewhere else.