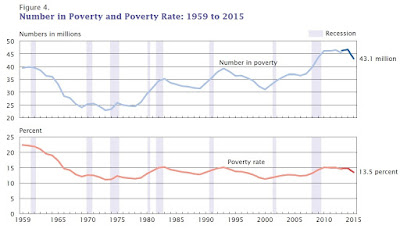

But the poverty line reported each year by the Census Bureau does have the merit that, for all its faults, it has been calculated in pretty much the same way for a long time now. The Census Bureau just released its estimates for the poverty rate in 2015 in its report, Income and Poverty in the United States: 2015, co-authored by Bernadette D. Proctor, Jessica L. Semega, and Melissa A. Kollar (September 2016, P60-256). As the report notes, "Real median household income increased 5.2 percent between 2014 and 2015. This is the first annual increase in median household income since 2007. ... The number of full-time, year-round workers increased by 2.4 million in 2015." Given those changes, it's not a big surprise that "The official poverty rate decreased by 1.2 percentage points between 2014 and 2015. ... he number of people in poverty fell by 3.5 million between 2014

and 2015."

Here are a few illustrative figures. The first shows the poverty rate, with all it warts and flaws, over time. The slightly different color of the lines after 2013 is because the wording of the underlying survey was slightly altered in that year.

Back in the 1960s, the poverty rate was higher for the elderly than for children or adults aged 18-64. But with the expansion of Social Security and Medicare over time, and a larger share of children being born into single-parent families below or near the poverty line, the poverty rate for children has been higher than for adults since the late 1970s.

Poverty rates are also lower for married for married-couple families and especially high for families with a "female household, no husband present."

But while poverty is conventionally measured by income, or income plus access to government benefits, a fuller understanding of what it means to be poor needs to reach beyond income and consumption. Frank Schilbach, Heather Schofield, and Sendhil Mullainathan offer an overview of some social science research in this area in "The Psychological Lives of the Poor," which appeared in the American Economic Review: Papers & Proceedings (May 2016, 106:5, 435–440). (The volume is not freely available online, but many readers will have access through a library subscription.) The authors argue that those in poverty suffer in a number of ways from less mental "bandwidth." They write (citations and footnotes omitted):

First, a large body of work points toward a two- system model of the brain. System 1 thinks fast: it is intuitive, automatic, and effortless, and as a result, prone to biases and errors. System 2 is slow, effortful, deliberate, and costly, but typically produces more unbiased and accurate results. Second, when mentally taxed, people are less likely to engage their System 2 processes. Put simply, one might think of having a (mental) reserve or capacity for the kind of effortful thought required to use System 2. When burdened, there is less of this resource available for use in other judgments and decisions. Though there is no commonly accepted name for this capacity, we will refer to it in this article as “bandwidth”.

Psychologists often study this underlying resource by imposing “cognitive load” to tax bandwidth and measure the impact on judgments and decisions. The many ways to induce load produce similar results on various bandwidth measures and consequences from reduced System 2 thinking. This insight is particularly useful because it implies that bandwidth is both malleable and measurable. It also suggests a unified approach of studying the psychology of poverty. We can understand factors in the lives of the poor, such as malnutrition, alcohol consumption, or sleep deprivation, by how

they affect bandwidth. And we can understand important decisions made by the poor, such as technology adoption or savings, through the lens of how they are affected by bandwidth. Clearly, bandwidth is not the only important aspect of the psychological lives of the poor; no single metric can take on this role. However, it provides a way to at least partly understand a great many of the thought processes that drive decision-making by the poor. ....

[T]here are reasons to believe that the effects of diminished bandwidth are larger for the poor. Individuals in poverty are more likely to be exposed to many of these factors (e.g., malnutrition, pain, heat) and to experience them more extensively. Further, the poor are less likely to have coping mechanisms, such as direct deposits or automatic enrollments, available to reduce the negative effects of limited bandwidth. Not only is their exposure greater, but the “same mistake” is likely to be more costly for the poor than for the rich. Finally, money is a potential substitute for bandwidth. It is often possible to buy yourself the extra slack you need—hiring someone to cook and clean—or to reduce the factors which lead to lower bandwidth—purchasing a comfortable bed in a quiet neighborhood.In short, the poor do not only suffer from lack of income. They also suffer from limits on bandwidth that affect the ability to remember decisions that need to be made in the future, or "executive control" functions that affect self-control about consumption or saving, or the ability to evaluate risks and benefits accurately. There is also some limited evidence that people under cognitive stress in one area (like hunger or finances) may gain less pleasure from other activities as well--a sort of extra tax on happiness that is imposed by limited bandwidth and poverty. Understanding what policies might help the poor to help themselves, whether in high-income or low-income countries, means coming to grips with how people act when stress is high and bandwidth is low.

A couple of years ago when the poverty rate was released, I wrote a post on "Empathy for the Poor: A Meditation" (September 17, 2014). In that post, I quoted George Orwell's discussion in his 1937 book, The Road to Wigan Pier, where he makes the case that the poor have adapted to a world to a world of cheap luxuries, including fish-and-chips and the electronic connections that allow them to focus on celebrity culture and sports betting. To me, it has an uncomfortably modern ring in describing a set of potential psychological adaptations for people who find themselves with limited bandwidth. Here's a quotation from Orwell, sliced from that earlier post:

"What we have lost in food we have gained in electricity. Whole sections of the working class who have been plundered of all they really need are being compensated, in part, by cheap luxuries which mitigate the surface of life.

"Do you consider all this desirable? No, I don't. But it may be that the psychological adjustment which the working class are visibly making is the best they could make in the circumstances. They have neither turned revolutionary nor lost their self-respect; merely they have kept their tempers and settled down to make the best of things on a fish-and-chip standard. . . . Of course the post-war development of cheap luxuries has been a very fortunate thing for our rulers. It is quite likely that fish-and-chips, art-silk stockings, tinned salmon, cut-price chocolate (five two-ounce bars for sixpence), the movies, the radio, strong tea, and the Football Pools have between them averted revolution. Therefore we are sometimes told that the whole thing is an astute manoeuvre by the governing class--a sort of 'bread and circuses' business--to hold the unemployed down. What I have seen of our governing class does not convince me that they have that much intelligence. The thing has happened, but by an unconscious process--the quite natural interaction between the manufacturer's need for a market and the need of half-starved people for cheap palliatives."When discussing the poverty rate, someone is sure to point out that even most people below the poverty line in the modern United States have access to sufficient calories, television, and cellphones. It's of course true that poverty in the modern United States isn't like poverty in 19th century Dickensian England. But it remains much harder for people in poverty, and their children, to flourish.