In a similar spirit, I of course know that the introduction of a printing press with moveable type by to Europe in 1439 by Johannes Gutenberg is often called one of the most important inventions in world history. However, I'm grateful that Jeremiah Dittmar and Skipper Seabold have been checking it out. They have written "Gutenberg’s moving type propelled Europe towards the scientific revolution," for the LSE Business Review (March 19, 2019). It's a nice accessible version of the main findings from their research paper, "New Media and Competition: Printing and Europe'sTransformation after Gutenberg" (Centre for Economic Perfomance Discussion Paper No 1600 January 2019). They write:

"Printing was not only a new technology: it also introduced new forms of competition into European society. Most directly, printing was one of the first industries in which production was organised by for-profit capitalist firms. These firms incurred large fixed costs and competed in highly concentrated local markets. Equally fundamentally – and reflecting this industrial organisation – printing transformed competition in the ‘market for ideas’. Famously, printing was at the heart of the Protestant Reformation, which breached the religious monopoly of the Catholic Church. But printing’s influence on competition among ideas and producers of ideas also propelled Europe towards the scientific revolution.While Gutenberg’s press is widely believed to be one of the most important technologies in history, there is very little evidence on how printing influenced the price of books, labour markets and the production of knowledge – and no research has considered how the economics of printing influenced the use of the technology."

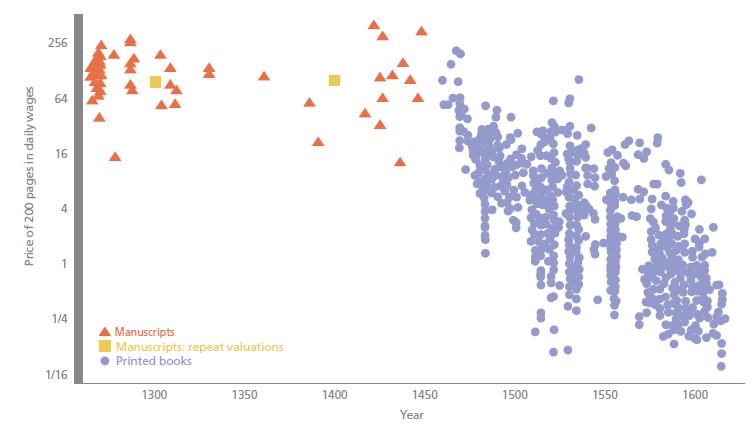

Dittmar and Seabold aim to provide some of this evidence. For example, here's their data on how the price of 200 pages changed over time, measured in terms of daily wages. (Notice that the left-hand axis is a logarithmic graph.) The price of a book went from weeks of daily wages to much less than one day of daily wages.

They write: "Following the introduction of printing, book prices fell steadily. The raw price of books fell by 2.4 per cent a year for over a hundred years after Gutenberg. Taking account of differences in content and the physical characteristics of books, such as formatting, illustrations and the use of multiple ink colours, prices fell by 1.7 per cent a year. ... [I]n places where there was an increase in competition among printers, prices fell swiftly and dramatically. We find that when an additional printing firm entered a given city market, book prices there fell by 25%. The price declines associated with shifting from monopoly to having multiple firms in a market was even larger. Price competition drove printers to compete on non-price dimensions, notably on product differentiation. This had implications for the spread of ideas."

Another part of this change was that books were produced for ordinary people in the language they spoke, not just in Latin. Another part was that wages for professors at universities rose relative to the average worker, and the curriculum of universities shifted toward the scientific subjects of the time like "anatomy, astronomy, medicine and natural philosophy," rather than theology and law.

The ability to print books affected religious debates as well, like the spread of Protestant ideas after Martin Luther circulated his 95 theses criticizing the Catholic Church in 1517.

Printing also affected the spread of technology and business.

Previous economic research has studied the extensive margin of technology diffusion, comparing the development of cities that did and did not have printing in the late 1400s ... Printing provided a new channel for the diffusion of knowledge about business practices. The first mathematics texts printed in Europe were ‘commercial arithmetics’, which provided instruction for merchants. With printing, a business education literature emerged that lowered the costs of knowledge for merchants. The key innovations involved applied mathematics, accounting techniques and cashless payments systems.It is impossible to avoid wondering if economic historians in 50 or 100 years will be looking back on the spread of internet technology, and how it affected patterns of technology diffusion, human capital, and social beliefs--and how differing levels of competition in the market may affect these outcomes.

The evidence on printing suggests that, indeed, these ideas were associated with significant differences in local economic dynamism and reflected the industrial structure of printing itself. Where competition in the specialist business education press increased, these books became suddenly more widely available and in the historical record, we observe more people making notable achievements in broadly bourgeois careers.