US investors of all types--individual, corporate, government--purchase debt and equity issued in other countries. International investors of all types--individual, corporate, government--purchase debt and equity issued in the United State. The US Bureau of Economic Analysis estimates the total holdings of foreign assets by US investors, and the total holdings of US assets by foreign investors. Here's the tally from the BEA:

Back in 2011, US-owned assets abroad (blue line) were about $2.5 trillion less than the US liabilities owned by foreign investors (orange line). At the end of 2020, the gap had risen to $14 trillion. This is the US "net international investment position."

This gap can change for two main reasons. One reason is that, in a given year, the inflow and outflow of financial investments to and from the US economy don't need to balance. In fact, when the US economy runs trade deficits, with imports greater than exports, it necessarily means that the US economy is consuming (with imports included) more than it is producing (with exports included). As economists are quick to point out, the result of this situation is that foreign parties will take some of the US dollars they have earned, and invest them in US financial assets.

The other reason the gap can change is that prices of financial assets can move around. For example, the S&P 500 stock market index has more than tripled in the last decade. Thus, the liabilities of the US economy to foreign investors who purchased US stocks a decade ago will be much larger as a result. Indeed, the BEA estimates that the value of foreign holdings of US portfolio assets--that is, holding debt or equity, but not with control of the US company--rose from $12 trillion a decade ago to more than $24 trillion at present, thus accounting for essentially all of the larger gap between US foreign assets and US foreign liabilities shown in the figure above. When comparing the size of foreign assets and liabilities over time, movements in exchange rates will also matter.

Because the value of US foreign liabilities exceeds that of US foreign assets, the US is sometimes referred to as a "debtor nation." The name isn't quite right for several reasons. When you read about the "national debt," the reference is usually to the accumulated debt from US government borrowing. But while this measure included government debt that is involved international investment decisions, it also include private sector choices about international investments in debt and equity as well.

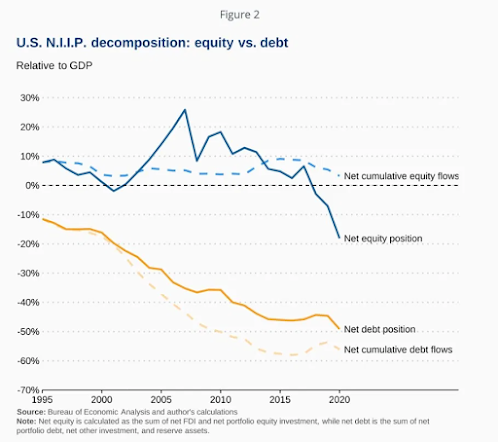

The figure shows that the common pattern for the US economy during the last quarter-century is that foreign investors hold much more in US-issued debt than US investors hold in foreign debt. One main reason for that is that US-dollar debt--especially the debt issued by the US government, is viewed around the world as a safe asset. The

US dollar has been the world's dominant currency for a long time.

However, during the last 25 years, US investors have tended to hold more in international equity than foreign investors held in US equity. The dashed blue line shows that flows of equity investment back and forth across the border haven't changed a lot. But because of the sharp rise in US stock markets, and also the stronger value of the US dollar, the total value of foreign holdings of US equity have risen compared to US holdings of foreign equity--and the US net international investment position has fallen accordingly. Milesi-Ferretti writes:

Since 2010, ... the net international investment position has plunged by some 50 percent of GDP. This time the valuation effects have worked in reverse: the U.S. dollar has strengthened notably since 2010, and U.S. equity prices have risen much more than foreign equity prices. In other words, the value of foreigners’ investments in the U.S. has risen a lot relative to the value of Americans’ investments abroad.

Thus, one way to look at the fall in US net international investment position is that it's the result of good news--a rising US stock market.

The other important pattern here is that, in general, if you have $100 in debt it will pay a lower return than $100 in equity, basically because the debt is safer than the equity. The US investment in foreign equity is often in the form of "foreign direct investment," where a US firm owns a large enough share of a foreign firm that the US firm has a say in managing the foreign firm (although the US firm may not have complete control over the foreign firm). This means that US investments abroad systematically earn more than foreign investments in the US. Here's a figure from Milesi-Ferretti:

Indeed, even though the rest of the world owns $14 trillion more in US assets than US investors own in foreign assets, it has been and continues to be true that the actual total returns paid on assets held in other countries is higher for US investors holding foreign assets than it is for foreign investors holding US assets.

I sometimes say that when it comes to international investment, the US economy is like a company that borrows money at a low interest rate and then invests that money in corporate stock and receives a higher rate of return. There are of course risks to this approach, but it's been this way for the US economy for a long time and there are clearly benefits, too.