"In October 2008, the Emergency Economic Stabilization

Act of 2008 (Division A of Public Law 110-343) established the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) to

enable the Department of the Treasury to promote

stability in financial markets through the purchase and

guarantee of `troubled assets.'” The Congressional Budget Office offers a retrospective on how the controversial program all turned out in "Report on the Troubled Asset Relief Program—April 2019."

One issue (although certainly not the only one) is whether the bailout was mostly a matter of loans or asset purchases that were later repaid. A bailout that was later repaid might still be offensive on various ground, but at least it would seem preferable to a bailout that was not repaid.

As a reminder, TARP authorized the purchase of $700 billion in "troubled assets." The program ended up spending $441 billion. Of that amount, $377 billion was repaid, $65 billion has been written off so far, and the remaining $2 billion seems likely to be written off in the future. Here's the breakdown:

Interestingly, the biggest single area of TARP write-offs was not the corporate bailouts, but the $29 billion for "Mortgage Programs." The CBO writes: "The Treasury initially committed a total of $50 billion in TARP funds for programs to help homeowners avoid foreclosure. Subsequent legislation reduced that amount, and CBO anticipates that $31 billion will ultimately be disbursed. About $10 billion of that total was designated for grants to certain state housing finance agencies and for programs of the Federal Housing Administration. Through February 28, 2019, total disbursements of

TARP funds for all mortgage programs were roughly $29 billion. Because most of those funds were in the form of direct grants that do not require repayment, the government’s cost is generally equal to the full amount disbursed."

The second-largest category of write-offs is the $17 billion for the GM and Chrysler. Here's my early take on "The GM and Chrysler Bailouts" (May 7, 2012). For a look at the deal from the perspective of two economists working for the Obama administration at the time, see Austan D. Goolsbee and Alan B. Krueger," A Retrospective Look at Rescuing and Restructuring General Motors and Chrysler," in the Spring 2015 issue of the Journal of Economic Perspectives.

Not far behind is the bailout for the insurance company AIG. It lost $50 billion making large investments and selling insurance on financial assets base on the belief that the price of real estate would not fall. The US Treasury writes: "At the time, AIG was the largest provider of conventional insurance in the world. Millions depended on it for their life savings and it had a huge presence in many critical financial markets, including municipal bonds." A few years back, I wrote about "Revisiting the AIG Bailout" (June 18, 2015), based in substantial part on "AIG in Hindsight," by Robert McDonald and Anna Paulson in the Spring 2015 issue of the Journal of Economic Perspectives.

Finally, the Capital Purchase Program involved buying stock in about 700 different financial institutions. Almost all of that stock has now been resold (about $20 million remains), and the government ended up writing off $5 billion overall.

Of these programs, I'm probably most skeptical about the auto bailouts, but even there, the risk of disruption from a disorderly bankruptcy, spreading from the companies to their suppliers to the surrounding communities, was disturbingly high. The purchases of stock in financial institutions, which may have been the most controversial step at the time, also came the closest to being repaid in full.

In the end, one's beliefs about whether TARP was a good idea depend on one's view of the US economy in October 2008. My own sense is that the US economy was in extraordinary danger during that month. B all means, let's figure out ways to improve the financial system so that future meltdowns are less likely, and I've argued "Why US Financial Regulators are Unprepared for the Next Financial Crisis" (February 11, 2019). But when someone is in the middle of having a heart attack, it's time for emergency action rather than a lecture on diet and exercise. And when an economy is in the middle of a severe and widespread financial meltdown, which had a real risk of turning out even worse than what actually happened, the government needs to accept that however its regulators failed in the past and need to reform in the future, emergency actions including bailouts may need to be used. I do sometimes wonder if the TARP controversy would have been lessened if more individuals had been held accountable for their actions (or sometimes lack of action) in the lead-up to the crisis.

Tuesday, April 30, 2019

Monday, April 29, 2019

Did Disability Insurance Just Fix Itself?

Back in 2015, the trust fund for the Social Security Disability Insurance Trust Fund was in deep trouble, scheduled to run out of money by 2016. A short-term legislative fix bought a few years more solvency for the trust fund, by moving some of the payroll tax for other Social Security benefits over to the disability trust fund, but the situation continued to look dire. For some of my previous takes on the situation, see this from 2016, this from 2013, or this from 2011. Or see this three-paper symposium on disability insurance from the Spring 2015 Journal of Economic Perspectives, with a discussion of what what going wrong in the US system and discussions of reforms from the Netherlands and the UK.

Well, the report of the 2019 Annual Report of the Board of Trustees of the Federal Old-Age and Survivors Insurance and the Federal Disability Insurance Trust Funds was recently published. And it now projects that the Disability Insurance trust fund won't run out for 33 years. In that sense, Disability Insurance looks to be in better shape than Medicare or the retirement portion of Social Security. What just happened?

This figure from the trustees shows the "prevalence rate" of disability--the rate of those receiving disability per 1,000 workers. The dashed line shows the actual prevalence of disability. The solid line shows the change after adjusting for age and sex. You can see the sharp rise in disability prevalence over several decades leading up to about 2014, which was leading to the concerns about the solvency of the system mentioned above. And then you see a drop in the prevalence of disability--both in the gross and the age-sex-adjusted lines.

As Henry Aaron writes: "What happened next has stunned actuaries, economists, and analysts of all stripes. The number of people applying for disability benefits dropped…and kept on dropping. Some decline was expected as the economy recovered from the Great Recession and demand for workers increased. But the actual fall in applications has dwarfed expectations. In addition, the share of applicants approved for benefits has also fallen. ... And if the drop in applications persists, current revenues may be adequate to cover currently scheduled benefits indefinitely."

Of course, the disability rate can fall for a number of reasons, some more welcome than others. To the extent that employment growth and a low unemployment rate has offered people a chance to find jobs in the paid workforce, rather than applying for disability, this seems clearly a good thing. But if this shift resulted from tightening the legal requirements on disability, then we might want to look more closely at whether this tightening made sense. The trust fund actuaries don't make judgments on this issue, but here are some bits of evidence.

The Center for Budget and Policy Priorities publishes a "Chart Book: Social Security Disability Insurance," with the most recent version coming out last August. The first figure shows that applications for disability have been falling in recent years. The second figure shows that the number of applications being accepted have also fallen since about 2010 at all three possible stages of the process: initial

It's not easy to make a judgement on these patterns. A common concern among researchers studying this issues is that the standards for granting disability, and the resulting number of disabled workers, seem to vary a lot across different locations and decision-makers. For example, the CPBB report offers this figure showing differences across states:

A report from the Congressional Research Service, "Trends in Social Security Disability InsuranceEnrollment" (November 30, 2018), describes some potential causes of the lower disability rates.

Well, the report of the 2019 Annual Report of the Board of Trustees of the Federal Old-Age and Survivors Insurance and the Federal Disability Insurance Trust Funds was recently published. And it now projects that the Disability Insurance trust fund won't run out for 33 years. In that sense, Disability Insurance looks to be in better shape than Medicare or the retirement portion of Social Security. What just happened?

This figure from the trustees shows the "prevalence rate" of disability--the rate of those receiving disability per 1,000 workers. The dashed line shows the actual prevalence of disability. The solid line shows the change after adjusting for age and sex. You can see the sharp rise in disability prevalence over several decades leading up to about 2014, which was leading to the concerns about the solvency of the system mentioned above. And then you see a drop in the prevalence of disability--both in the gross and the age-sex-adjusted lines.

As Henry Aaron writes: "What happened next has stunned actuaries, economists, and analysts of all stripes. The number of people applying for disability benefits dropped…and kept on dropping. Some decline was expected as the economy recovered from the Great Recession and demand for workers increased. But the actual fall in applications has dwarfed expectations. In addition, the share of applicants approved for benefits has also fallen. ... And if the drop in applications persists, current revenues may be adequate to cover currently scheduled benefits indefinitely."

Of course, the disability rate can fall for a number of reasons, some more welcome than others. To the extent that employment growth and a low unemployment rate has offered people a chance to find jobs in the paid workforce, rather than applying for disability, this seems clearly a good thing. But if this shift resulted from tightening the legal requirements on disability, then we might want to look more closely at whether this tightening made sense. The trust fund actuaries don't make judgments on this issue, but here are some bits of evidence.

The Center for Budget and Policy Priorities publishes a "Chart Book: Social Security Disability Insurance," with the most recent version coming out last August. The first figure shows that applications for disability have been falling in recent years. The second figure shows that the number of applications being accepted have also fallen since about 2010 at all three possible stages of the process: initial

It's not easy to make a judgement on these patterns. A common concern among researchers studying this issues is that the standards for granting disability, and the resulting number of disabled workers, seem to vary a lot across different locations and decision-makers. For example, the CPBB report offers this figure showing differences across states:

A report from the Congressional Research Service, "Trends in Social Security Disability InsuranceEnrollment" (November 30, 2018), describes some potential causes of the lower disability rates.

Since 2010, new awards to disabled workers have decreased every year, dropping from 1 million to 762,100 in 2017. Although there has been no definitive cause identified, four factors may explain some of the decline in disability awards.

- Availability of jobs. The unemployment rate was as high as 9.6% in 2010 and then gradually decreased every year to about 4.35% in 2017. ...

- Aging of lower-birth-rate cohorts. The lower-birth-rate cohorts (people born after 1964) started to enter peak disability-claiming years (usually considered ages 50 to FRA [federal retirement age]) in 2015, replacing the larger baby boom population. This transition would likely reduce the size of insured population who are ages 50 and above, as well as the number of disability applications. ...

- Availability of Affordable Care Act (ACA). ... Yhe availability of health insurance under the ACA may lower the incentive to use SSDI as a means of access to Medicare, thus reducing the number of disability applications. ...

- Decline in the allowance rate. The total allowance rate at all adjudicative levels declined from 62% in 2001 to 48% in 2016. While this decline may in part reflect the impact of the Great Recession (since SSDI allowance rates typically fall during an economic downturn), the Social Security Advisory Board Technical Panel suspects that the declining initial allowance rate may be a result of the change in the SSDI adjudication process.

The Social Security actuaries are projecting that the share of Americans getting disability insurance isn't going to change much over time. But given the experience of the last few years, one's confidence in that projection is bound to be shaky.

Saturday, April 27, 2019

When Special Interests Play in the Sunlight

There's a common presumption in American politics that special interests are more likely to hold sway during secret negotiations in back rooms, while the broader public interest is more likely to win out in a transparent and open process. People making this case often quote Louis Brandeis, from his 1914 book Other People's Money: "Publicity is justly commended as a remedy for social and industrial diseases. Sunlight is said to be the best of disinfectants ..." This use of the sunlight metaphor wasn't original to Brandeis: for example, James Bryce also used it in an 1888 book The American Commonwealth.

But what if, at least in some important settings, the reverse is true? What if public processes that are more public actually result in greater power for special interests and less ability to find workable compromise solutions? James D'Angelo and Brent Ranall make this case in their essay "The Dark Side of Sunlight: How Transparency Helps Lobbyists and Hurts the Public," which appears in the May/June 2019 issue of Foreign Affairs. Responding to the Brandeis metaphor, they write: "Endless sunshine—without some occasional shade—kills what it is meant to nourish."

The underlying argument goes something like this. Many of us have a reflexive belief that open political processes are more accountable, but we don't often ask "accountable to who"? It's easy to assume that the accountability is to a broader public interest. But in practice, transparency means that focused special interests can keep tabs on each proposal. If the special interests object, they can whip up a storm of protests. They also can threaten attempts at compromise, and push instead toward holding hard lines and party lines. Greater openness means a greater ability to monitor, to pressure, and to punish possible and perceived deviations.

In US political history, the emphasis on sunlight is a relatively recent development. D'Angelo and Ranall point out:

D'Angelo and Ranall argue that a number of the less attractive features of American politics are tied to the push for greater transparency and openness. For example, we now have cameras operating in the House and Senate, which on rare occasions capture actual debate, but are more commonly used as a stage backdrop for politicians recording something for use in their next fundraiser or political ad. When public votes are taken much more often, then more votes are also taken just for show in an attempt to rally one's supporters or to embarrass the other party, rather than for any substantive legislative purpose. Politicians who are always on-stage are likely to display less civility and collegiality and greater polarization, lest they be perceived as insufficiently devoted to their own causes---or even showing the dreaded signs of a willingness to compromise.

As D'Angelo and Ranall point out, it's interesting to note that when politicians are really serious about something, like gathering in a caucus to choose a party leader, they use a secret ballot. They write: "Just as the introduction of the secret ballot in popular elections in the late nineteenth century put an end to widespread bribery and voter intimidation—gone were the orgies of free beer and sandwiches—it could achieve the same effect in Congress."

It's important to remember that here are wide array of forums, step-by-step process, and decisions that feed into any political process. Thus, the choice between secrecy and transparency isn't a binary one: that is, one doesn't need to be in favor of total openness or total secrecy in all situations. D'Angelo and Ranall make a strong case toward questioning the reflexive presumption that more transparency in all settings will lead to better political outcomes.

But what if, at least in some important settings, the reverse is true? What if public processes that are more public actually result in greater power for special interests and less ability to find workable compromise solutions? James D'Angelo and Brent Ranall make this case in their essay "The Dark Side of Sunlight: How Transparency Helps Lobbyists and Hurts the Public," which appears in the May/June 2019 issue of Foreign Affairs. Responding to the Brandeis metaphor, they write: "Endless sunshine—without some occasional shade—kills what it is meant to nourish."

The underlying argument goes something like this. Many of us have a reflexive belief that open political processes are more accountable, but we don't often ask "accountable to who"? It's easy to assume that the accountability is to a broader public interest. But in practice, transparency means that focused special interests can keep tabs on each proposal. If the special interests object, they can whip up a storm of protests. They also can threaten attempts at compromise, and push instead toward holding hard lines and party lines. Greater openness means a greater ability to monitor, to pressure, and to punish possible and perceived deviations.

In US political history, the emphasis on sunlight is a relatively recent development. D'Angelo and Ranall point out:

It used to be that secrecy was seen as essential to good government, especially when it came to crafting legislation. Terrified of outside pressures, the framers of the U.S. Constitution worked in strict privacy, boarding up the windows of Independence Hall and stationing armed sentinels at the door. As Alexander Hamilton later explained, “Had the deliberations been open while going on, the clamors of faction would have prevented any satisfactory result.” James Madison concurred, claiming, “No Constitution would ever have been adopted by the convention if the debates had been public.” The Founding Fathers even wrote opacity into the Constitution, permitting legislators to withhold publication of the parts of proceedings that “may in their Judgment require Secrecy.” ...

One of the first acts of the U.S. House of Representatives was to establish the Committee of the Whole, a grouping that encompasses all representatives but operates under less formal rules than the House in full session, with no record kept of individual members’ votes. Much of the House’s most important business, such as debating and amending the legislation that comes out of the various standing committees—Ways and Means, Foreign Affairs, and so on—took place in the Committee of the Whole (and still does). The standing committees, meanwhile, in both the House and the Senate, normally marked up bills behind closed doors, and the most powerful ones did all their business that way. As a result, as the scholar George Kennedy has explained, “Virtually all the meetings at which bills were actually written or voted on were closed to the public.”

For 180 years, secrecy suited legislators well. It gave them the cover they needed to say no to petitioners and shut down wasteful programs, the ambiguity they needed to keep multiple constituencies happy, and the privacy they needed to maintain a working decorum.But starting in the late 1960s and early 1970s, we have now had a half-century of experimenting with more open processes. How is that working out? When greater transparency in Congress arrived in the 1970s, did that mean special interest had more power or less? There's a simple (if imperfect) test. If special interests had less power, then it would not have been worthwhile to invest as much in lobbying, so more transparency should have been followed by a reduction in lobbying. Of course, the reverse is what actually happened: Lobbying rose dramatically in the 1970s, and has risen further since then. Apparently, greater political openness makes spending on lobbying more worthwhile, not less.

D'Angelo and Ranall argue that a number of the less attractive features of American politics are tied to the push for greater transparency and openness. For example, we now have cameras operating in the House and Senate, which on rare occasions capture actual debate, but are more commonly used as a stage backdrop for politicians recording something for use in their next fundraiser or political ad. When public votes are taken much more often, then more votes are also taken just for show in an attempt to rally one's supporters or to embarrass the other party, rather than for any substantive legislative purpose. Politicians who are always on-stage are likely to display less civility and collegiality and greater polarization, lest they be perceived as insufficiently devoted to their own causes---or even showing the dreaded signs of a willingness to compromise.

As D'Angelo and Ranall point out, it's interesting to note that when politicians are really serious about something, like gathering in a caucus to choose a party leader, they use a secret ballot. They write: "Just as the introduction of the secret ballot in popular elections in the late nineteenth century put an end to widespread bribery and voter intimidation—gone were the orgies of free beer and sandwiches—it could achieve the same effect in Congress."

It's important to remember that here are wide array of forums, step-by-step process, and decisions that feed into any political process. Thus, the choice between secrecy and transparency isn't a binary one: that is, one doesn't need to be in favor of total openness or total secrecy in all situations. D'Angelo and Ranall make a strong case toward questioning the reflexive presumption that more transparency in all settings will lead to better political outcomes.

Friday, April 26, 2019

Washing Machine Tariffs: Who Paid? Who Benefits?

When import tariffs are proposed, there's a lot of talk about unfairness and helping workers. But when the tariffs are enacted, the standard pattern is that consumers pay more, profits for the protected firm go up, and jobs are reshuffled from unprotected to protected industries. Back in 1911, satirist Ambrose Bierce defined "tariff" this way in The Devil's Dictionary: "TARIFF, n.A scale of taxes on imports, designed to protect the domestic producer against the greed of his consumer."

Back in fall 2017, the Trump administration announced worldwide tariffs on imported washing machines. Aaron Flaaen, Ali Hortaçsu, and Felix Tintelnot, look at the results in “The Production, Relocation, and Price Effects of US Trade Policy: The Case of Washing Machines.” A readable overview of their work is here; the underlying research paper is here.

Back in fall 2017, the Trump administration announced worldwide tariffs on imported washing machines. Aaron Flaaen, Ali Hortaçsu, and Felix Tintelnot, look at the results in “The Production, Relocation, and Price Effects of US Trade Policy: The Case of Washing Machines.” A readable overview of their work is here; the underlying research paper is here.

One semi-comic aspect of the washing machine tariffs was that "unfairness" of lower-priced washing machines from abroad has been hopscotching across countries for a few years now. Back in 2011, South Korea and Mexico were the two leading exporters of washing machines to the US. They were accused of selling at unfairly low prices. But even as the anti-dumping investigation was announced, washing machine imports from those countries dropped sharply. China became the new leading exporter of washing machines to the US--essentially taking South Korea's market share.

China was then being accused of selling washing machines to US consumers at unfairly low prices. But by the time the anti-dumping investigation against China started and was concluded in mid-2016, China's exports of washing machines to the US had dropped off. Thailand and Vietnam had become the main exporters of washing machines to the US. Tired of chasing the imports of low-priced washing machined from country to country, the Trump administration announced worldwide tariffs on washing machines late in 2017, and they took effect early in 2018.

If one country is selling imports at an unfairly low price, one can at least argue that this practice is unfair. But when a series of countries are all willing to sell at a lower price, it strongly suggests that the issue a country-hopping kind of unfairness, leaping from one country to another, but instead reflects a reality that there are a lot of places around the world where washing machines that Americans want to buy can be produced cheaply.

The results of the washing machine tariffs were as expected. Prices to consumers rose. As the authors write:

Following the late-2017 announcement of tariffs on all washers imported to the United States, prices increased by about 12 percent in the first half of 2018 compared to a control group of other appliances. In addition, prices for dryers—often purchased in tandem with washing machines—also rose by about 12 percent, even though dryers were not subject to a tariff. ... [T]hese price increases were unsurprising given the tariff announcement. ... One revealing finding in this work is the tight price relationship between washers and dryers, even when washers, for example, are the product that is subject to tariffs. Among the five leading manufacturers of washers, roughly three- quarters of models have matching dryers. When the authors compare only electric washers and dryers, they show that in about 85 percent of the matching sets, the washers and dryers have the same price.

Yes, the domestic makers of washing machines with factories in the US like Whirlpool, Samsung and LG announced plans to hire a few thousand more workers in response to the tariffs. But a substantial share of the higher prices paid by consumers just went into higher corporate profits for these companies. For example, the most recent reports from Whirlpool suggest that the overall pattern is selling fewer machines, with higher profits margins per machine.

When Flaaen, Hortaçsu, and Tintelnot estimate the total in higher prices paid by consumers, and divide by an estimate of the number of jobs saved or created in the washing machine industry, they write: "The increases in consumer prices described above

translate into a total consumer cost of $1.5 billion

per year, or about $820,000 per new job."

You can tell all kinds of stories about tariffs, full of words like "unfairness" and "toughness" and "saving jobs." But the economic effects of the tariffs aren't determined by a desired story line. As Nikita Khrushchev is reputed to have said: "[E]conomics is a subject that does not greatly respect one's wishes." The reality of the washing machine tariffs is that consumers pay more for a basic consumer appliance and company profits go up. Some workers at the protected companies do benefit, but at a high price per job. The higher prices for washing machines means less spending on other goods, which together with tit-for-tat retaliation by other countries for the tariffs, leads to a loss of jobs elsewhere in the US economy. This story plays out over and over: for example, here's a story from the steel tariffs earlier in the Trump administration or the tire tariffs in the Obama administration. It is not a strategy for US economic prosperity.

Thursday, April 25, 2019

Financial Managers and Misconduct

"Financial advisers in the United States manage over $30 trillion in investible assets, and plan the financial futures of roughly half of U.S. households. At the same time, trust in the financial sector remains near all-time lows. The 2018 Edelman Trust Barometer ranks financial services as the least trusted sector by consumers, finding that only 54 percent of consumers `trust the financial services sector to do what is right.'"

Mark Egan, Gregor Matvos and Amit Seru went looking for actual data on misconduct by financial managers. Matvos and Seru provide an overview of their research in "The Labor Market for Financial Misconduct" (NBER Reporter 2019:1). For the details, see M. Egan, G. Matvos, and A. Seru, "The Market for Financial Adviser Misconduct," NBER Working Paper No. 22050, February 2016.

The authors figured out that the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority keeps a record of the complete employment history of the 1.2 million people registered as financial adviser from 2005-2015 at its BrokerCheck website. This history includes employers, jobs tasks, and roles. In addition, "FINRA requires financial advisers to formally disclose all customer complaints, disciplinary events, and financial matters, which we use to construct a measure of misconduct." They write:

Mark Egan, Gregor Matvos and Amit Seru went looking for actual data on misconduct by financial managers. Matvos and Seru provide an overview of their research in "The Labor Market for Financial Misconduct" (NBER Reporter 2019:1). For the details, see M. Egan, G. Matvos, and A. Seru, "The Market for Financial Adviser Misconduct," NBER Working Paper No. 22050, February 2016.

The authors figured out that the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority keeps a record of the complete employment history of the 1.2 million people registered as financial adviser from 2005-2015 at its BrokerCheck website. This history includes employers, jobs tasks, and roles. In addition, "FINRA requires financial advisers to formally disclose all customer complaints, disciplinary events, and financial matters, which we use to construct a measure of misconduct." They write:

Roughly one in 10 financial advisers who work with clients on a regular basis have a past record of misconduct. Common misconduct allegations include misrepresentation, unauthorized trading, and outright fraud— all events that could be interpreted as a conscious decision of the adviser. Adviser misconduct results in substantial costs: In our sample, the median settlement paid to consumers is $40,000, and the mean is $550,000. These settlements cost the financial industry almost half a billion dollars per year.Looking at this data generates some provocative insights.

When it comes to financial matters, there will of course inevitably be cases of frustrated expectations and hard feelings. But are the examples of misconduct spread out fairly evenly across all financial advisers, or is it the case that some advisers are responsible for most of the cases? They write:

"A substantial number of financial advisers are repeat offenders. Past offenders are five times more likely to engage in misconduct than otherwise comparable advisers in the same firm, at the same location, at the same point in time."

A common pattern is that a financial adviser is fired for misconduct at one firm. But then hired at another firm. They write: "Although firms are strict in disciplining misconduct, the industry as a whole undoes some of the discipline by recycling advisers with past records of misconduct. Roughly half of advisers who lose a job after engaging in misconduct find new employment in the industry within a year. In total, roughly 75 percent of those advisers who engage in misconduct remain active and employed in the industry the following year."

A common pattern is that a financial adviser is fired for misconduct at one firm. But then hired at another firm. They write: "Although firms are strict in disciplining misconduct, the industry as a whole undoes some of the discipline by recycling advisers with past records of misconduct. Roughly half of advisers who lose a job after engaging in misconduct find new employment in the industry within a year. In total, roughly 75 percent of those advisers who engage in misconduct remain active and employed in the industry the following year."

Just to give this skeeviness an extra twist, there appears to be gender bias against women in rehiring those involved in misconduct:

[W]e also find evidence of a "gender punishment gap." Following an incident of misconduct, female advisers are 9 percentage points more likely to lose their jobs than their male counterparts. ... After engaging in misconduct, 54 percent of male advisers retain their jobs the following year while only 45 percent of female advisers retain their jobs, despite no differences in turnover rates for male and female advisers without misconduct records (19 percent). ... While half of male advisers find new employment after losing their jobs following misconduct, only a third of female advisers find new employment. ... Because of the incredible richness of our regulatory data, we are able to compare the career outcomes of male and female advisers who are working at the same firm, in the same location, at the same point in time, and in the same job role. Differences in production, or the nature of misconduct, do not explain the gap. If anything, misconduct by female advisers is on average substantially less costly for firms. The gender punishment gap increases in firms with a larger share of male managers at the firm and branch levels.This process of firing and reshuffling leads to an outcome financial advisers involved in misconduct but then rehired tend to be clustered in some firms. "We find large differences in misconduct across some of the largest and best-known financial advisory firms in the U.S. Figure 1 displays the top 10 firms with the highest share of advisers that have a record of misconduct. Almost one in five financial advisers at Oppenheimer & Co. had a record of misconduct. Conversely, at USAA Financial Advisors, the ratio was less than one in 36."

As the authors point out, with academic understatement, this seems like a market that relies for its current method of operation on "unsophisticated consumers." But FINRA's BrokerCheck website is open to the public. It just seems to need wider use.

Wednesday, April 24, 2019

Two Can Live 1.414 Times as Cheaply as One: Household Equivalence Scales

A "household equivalence" scale offers an answer to this question: How much more income is needed by a a household with more people so that it has the same standard of living as a household with fewer people? The question may seem a little abstract, but it has immediate applications.

For example, the income level that officially defines the poverty line was $13,064 for a single-person household under age 65 in 2018. For a two-person household, the poverty line is $16,815 if they are both adults, but $17,308 if it's one adult and one child. For a single parent with two children the poverty line is $20,331; for a single parent with three children, it's $25,554. The extent to which the poverty line rises with the number of people, and with whether the people are adults or children or elderly, is a kind of equivalence scale.

Similarly, when benefits the poor and near-poor are adjusted by family size, such adjustments are based on a kind of equivalence scale.

And bigger picture, if you are comparing average household income between the early 1960s and the present, it presumably matters that the average household had 3.3 people in the early 1960s but closer to 2.5 people today (see Table HH-4).

However, it often turns out that poverty lines and poverty programs are set up with their own logic of what seems right at the time, but without necessarily using a common household equivalence scale. Richard V. Reeves and Christopher Pulliam offer a nice quick overview of the topic in "Tipping the balance: Why equivalence scales matter more than you think" (Brookings Institution, April 17, 2019). Here's a sample of some common household equivalence scales:

Reeves and Pulliam point out that if you look at the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, and how it affects "households" at different income levels, your answer will look different depending on whether you apply a household equivalence scale. For example, think about ranking households by income using an equivalence scale. If there are two households with the same income, but one household has more children, then the household with more children will be treated as having a lower standard of living (or to put it another way, a household with more children would need more income to have the same standard of living). The 2017 tax law provides substantial benefits to families with children.

But setting aside that particular issue, it's topic that matters to people planning a household budget, if they think about the question of whether living together will save money, or how much more money they will need if they have children. The commonly used "square root" approach, for example, suggests that a a household of two people will need 1.414 times the income of a single-person household for an equivalent standard of living, a household of three people will need 1.732 times the income of a single-person household for an equivalent standard of living and so on. Pick another household equivalence scale, if you prefer, but then plan accordingly.

For example, the income level that officially defines the poverty line was $13,064 for a single-person household under age 65 in 2018. For a two-person household, the poverty line is $16,815 if they are both adults, but $17,308 if it's one adult and one child. For a single parent with two children the poverty line is $20,331; for a single parent with three children, it's $25,554. The extent to which the poverty line rises with the number of people, and with whether the people are adults or children or elderly, is a kind of equivalence scale.

Similarly, when benefits the poor and near-poor are adjusted by family size, such adjustments are based on a kind of equivalence scale.

And bigger picture, if you are comparing average household income between the early 1960s and the present, it presumably matters that the average household had 3.3 people in the early 1960s but closer to 2.5 people today (see Table HH-4).

However, it often turns out that poverty lines and poverty programs are set up with their own logic of what seems right at the time, but without necessarily using a common household equivalence scale. Richard V. Reeves and Christopher Pulliam offer a nice quick overview of the topic in "Tipping the balance: Why equivalence scales matter more than you think" (Brookings Institution, April 17, 2019). Here's a sample of some common household equivalence scales:

Reeves and Pulliam point out that if you look at the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, and how it affects "households" at different income levels, your answer will look different depending on whether you apply a household equivalence scale. For example, think about ranking households by income using an equivalence scale. If there are two households with the same income, but one household has more children, then the household with more children will be treated as having a lower standard of living (or to put it another way, a household with more children would need more income to have the same standard of living). The 2017 tax law provides substantial benefits to families with children.

But setting aside that particular issue, it's topic that matters to people planning a household budget, if they think about the question of whether living together will save money, or how much more money they will need if they have children. The commonly used "square root" approach, for example, suggests that a a household of two people will need 1.414 times the income of a single-person household for an equivalent standard of living, a household of three people will need 1.732 times the income of a single-person household for an equivalent standard of living and so on. Pick another household equivalence scale, if you prefer, but then plan accordingly.

Tuesday, April 23, 2019

The Statute of Limitations on College Grades

As we move toward the end of the academic year for many colleges and universities, it is perhaps useful for students to be reminded that the final grade for any given course is quite unlikely to have a long-lasting influence on your life. Here are some thoughts from the syndicated newspaper column written by Calvin Trillin, which I would sometimes read to my introductory economics students on the last day of class. (I don't have an online link, but my notes tell me that I originally read the column in the San Jose Mercury News, May 26, 1990, p. 9C). Trillin wrote:

What I'm saying is that when it comes to college grades, there is a sort of statute of limitations.

It kicks in pretty early. By the time you're 28, nobody much cares whether or not you had to take Bonehead English or how you did in it. If you happen to be a pompous 28, wearing a Phi Beta Kappa key on your watch chain will make you seem more pompous. (If we're being absolutely truthful, the watch chain itself is a mistake.) Go ahead and tell that attractive young woman at the bar that you graduated magna cum laude. To employ a phrase I once heard from a country comedian in central Florida, `She just flat out do not care.' The statute of limitation has already run out.

This information about the statute of limitation ought to be comforting to the college seniors who are now limping toward commencement. In fact, it may be that commencement speakers -- some of whom, I regret to say, tend to wear Phi Beta Kappa keys on their watch chains -- ought to be telling the assembled degree recipients. Instead of saying 'life is a challenge' or 'commencement means beginning,' maybe a truly considerate commencement speaker would say, 'Take this degree, and, as to the question of how close you came to not getting it, your secret is safe with us.'

It's probably a good thing that after a while nobody cares. On the occasion of my college class' 25th reunion, I did a survey, using my usual scientific controls, and came to the conclusion that we had finally reached the point at which income seemed to be precisely in inverse proportion to academic standing in the class. I think this is the sort of information that students cramming desperately for the history final are better off not having.

Saturday, April 20, 2019

One Case for Keeping "Statistical Significance:" Beats the Alternatives

I wrote a few weeks back that the American Statistical Association has published a special issue of it journal, the American Statistician, with a lead article proposing the abolition of "statistical significance" ("Time to Abolish `Statistical Significance'"?). John Ioannidis has estimated that 90% of medical research is statistically flawed, so one might expect him to be among the harsher critics of statistical significance. But in the Journal of the American Medical Association, he goes the other way in "The Importance of Predefined Rules and Prespecified Statistical Analyses: Do Not Abandon Significance" (April 4, 2019). Here are a few of his themes:

The result of statistical research is often a yes-or-no outcome. Should a medical treatment be approved or not? Should a certain program or policy be expanded or cut? Should one potential effect be studied more, or should it be ruled out as a cause? Thus, while it's fine for researchers to emphasize that all results come with degree of uncertainty, at some point it's necessary to decide both how research and how applications of that research in the real world should proceed. Ioannidis writes:

The result of statistical research is often a yes-or-no outcome. Should a medical treatment be approved or not? Should a certain program or policy be expanded or cut? Should one potential effect be studied more, or should it be ruled out as a cause? Thus, while it's fine for researchers to emphasize that all results come with degree of uncertainty, at some point it's necessary to decide both how research and how applications of that research in the real world should proceed. Ioannidis writes:

Changing the approach to defining statistical and clinical significance has some merits; for example, embracing uncertainty, avoiding hyped claims with weak statistical support, and recognizing that “statistical significance” is often poorly understood. However, technical matters of abandoning statistical methods may require further thought and debate. Behind the so-called war on significance lie fundamental issues about the conduct and interpretation of research that extend beyond (mis)interpretation of statistical significance. These issues include what effect sizes should be of interest, how to replicate or refute research findings, and how to decide and act based on evidence. Inferences are unavoidably dichotomous—yes or no—in many scientific fields ranging from particle physics to agnostic omics analyses (ie, massive testing of millions of biological features without any a priori preference that one feature is likely to be more important than others) and to medicine. Dichotomous decisions are the rule in medicine and public health interventions. An intervention, such as a new drug, will either be licensed or not and will either be used or not.Yes, statistical significance has a number of problems. It would be foolish to rely on it exclusively. But what will be used instead? And will it be better or worse as a way of making such decisions? No method of making such decisions is proof against bias. Ioannidis writes:

Many fields of investigation (ranging from bench studies and animal experiments to observational population studies and even clinical trials) have major gaps in the ways they conduct, analyze, and report studies and lack protection from bias. Instead of trying to fix what is lacking and set better and clearer rules, one reaction is to overturn the tables and abolish any gatekeeping rules (such as removing the term statistical significance). However, potential for falsification is a prerequisite for science. Fields that obstinately resist refutation can hide behind the abolition of statistical significance but risk becoming self-ostracized from the remit of science. Significance (not just statistical) is essential both for science and for science-based action, and some filtering process is useful to avoid drowning in noise.

Ioannidis argues that the removal of statistical significance will tend to make things harder to rule out, because those who wish to believe something is true will find it easier to make that argument. Or more precisely:

Some skeptics maintain that there are few actionable effects and remain reluctant to endorse belabored policies and useless (or even harmful) interventions without very strong evidence. Conversely, some enthusiasts express concern about inaction, advocate for more policy, or think that new medications are not licensed quickly enough. Some scientists may be skeptical about some research questions and enthusiastic about others. The suggestion to abandon statistical significance1 espouses the perspective of enthusiasts: it raises concerns about unwarranted statements of “no difference” and unwarranted claims of refutation but does not address unwarranted claims of “difference” and unwarranted denial of refutation.The case for not treating statistical significance as the primary goal of an analysis seems to me ironclad. The case is strong for putting less emphasis on statistical significance and correspondingly more emphasis on issues like what data is used, the accuracy of data measurement, how the measurement corresponds to theory, the potential importance of a result, what factors may be confounding the analysis, and others. But the case for eliminating statistical significance from the language of research altogether, with the possibility that it will be replaced by an even squishier and more subjective decision process, is a harder one to make.

Friday, April 19, 2019

When Did the Blacksmiths Disappear?

In 1840, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow published a poem called "The Village Blacksmith." In my humble economist-opinion, not his best work. But the opening four lines are very nice:

Jeremy Atack and Robert A. Margo answer the question in "Gallman revisited: blacksmithing and American manufacturing, 1850–1870," published earlier this year in Cliometrica (2019, 13: 1-23). Gallman is an earlier writer who classified blacksmiths as a service industry, while Atack and Margo argue that they instead should be treated as an early form of manufacturing. From a modern view, given the concerns over how technology may affect current and future jobs, blacksmiths offer an example of how a prominent industry of skilled workers went away. Atack and Margo write:

Under a spreading chestnut treeWhen I was a little boy, and my father read the poem to me, I remember the pleasure in his voice at that word "sinewy." Indeed, there was at time when every town of even modest size had at least one blacksmith. When did they go away?

The village smithy stands;

The smith, a mighty man is he,

With large and sinewy hands ...

Jeremy Atack and Robert A. Margo answer the question in "Gallman revisited: blacksmithing and American manufacturing, 1850–1870," published earlier this year in Cliometrica (2019, 13: 1-23). Gallman is an earlier writer who classified blacksmiths as a service industry, while Atack and Margo argue that they instead should be treated as an early form of manufacturing. From a modern view, given the concerns over how technology may affect current and future jobs, blacksmiths offer an example of how a prominent industry of skilled workers went away. Atack and Margo write:

The village blacksmith was a common sight in early nineteenth-century American communities, along with cobblers, shoemakers, grist mill operators, and other artisans. Blacksmiths made goods from wrought iron or steel. This metal was heated in a forge until pliant enough to be worked with hand tools, such as a hammer, chisel, and an anvil. Others also worked with metal but what distinguished blacksmiths was their abilities to fashion a wide range of products from start to finish and even change the properties of the metal by activities such as tempering, as well as repair broken objects. ...

Blacksmiths produced a wide range of products and supplied important services to the nineteenth-century economy. In particular, they produced horseshoes and often acted as farriers, shoeing horses, mules, and oxen. This was a crucial service in an economy where these animals provided the most of the draft power on the farm and in transportation and carriage. The village blacksmith also produced a wide range of goods from agricultural implements to pots and pans, grilles, weapons, tools, and carriage wheels among many other items familiar and unfamiliar to a modern audience—a range of activities largely hidden behind their generic occupational title.

Blacksmithing was a sufficiently important activity to qualify as a separate industrial category in the nineteenth-century US manufacturing censuses, alongside more familiar industries as boots and shoes, flour milling, textiles, and clock making. The 1860 manufacturing census, for example, enumerated 7504 blacksmith shops employing 15,720 workers ... —in terms of the number of establishments, the fourth most common activity behind lumber milling, flour milling, and shoemaking. ...

As ‘‘jacks-of-all-trades,’’ they [blacksmiths] were generally masters of none (except for their service activities). Moreover, the historical record reveals that several of those who managed to achieve mastery moved on to become specialized manufacturers of that specific product. Such specialized producers had higher productivity levels than those calling themselves blacksmiths producing the same goods, explaining changes in industry mix and the decline of the blacksmith in manufacturing. ...

Consider the goods produced historically by blacksmiths, such as plows. Over time, blacksmiths produced fewer and fewer of these, concentrating instead on services like shoeing horses or repairs. But even controlling for this, only the most productive of blacksmiths (or else those whose market was protected from competition in some way) survived—a selection effect. On the goods side of the market, production shifted toward establishments that were sufficiently productive that they could specialize in a particular ‘‘industry,’’ such as John Deere in the agricultural implements industry. As this industry grew, it drew in workers—some of whom in an earlier era might have opened their own blacksmith shops, but most of whom now worked on the factory floor, perhaps doing some of the same tasks by hand that blacksmiths had done earlier but otherwise performing entirely novel tasks, because production process was increasingly mechanized. On average, such workers in the specialized industry were more productive than the ‘‘jack-of-all-trades,’’ the blacksmith, had been formerly. The village smithy could and did produce rakes and hoes, but the village smithy eventually and increasingly gave way to businesses like (John) Deere and Company who did it better. ...

During the first half of the nineteenth century, blacksmiths were ubiquitous in the USA, but by the end of the century they were no longer sufficiently numerous or important goods producers to qualify as a separate industry in the manufacturing census.

Thursday, April 18, 2019

When US Market Access is No Longer a Trump Card

When the US economy was a larger share of the world economy, then access to the US market meant more. For example, World Bank statistics say that the US economy was 40% of the entire world economy in 1960, but is now about 24%. The main source of growth in the world economy for the foreseeable future will be in emerging markets.

For a sense of the shift, consider this figure from chapter 4 of the most recent World Economic Outlook report, published by the IMF (April 2019). The lines in the figure show the trade flows between countries that are at least 1% of total world GDP. The size of the dots for each country is proportionate to the country's GDP.

In 1995, you can see international trade revolving around the United States, with another hub of trade happening in Europe and a third hub focused around Japan. Trade between the US and China shows up on the figure, but China did not have trade flows greater than 1% of world GDP with any country other than the US.

The picture is rather different in 2015. The US remains an international hub for trade. Germany remains a hub as well, although fewer of its trade flows now exceed 1% of world GDP. And China has clearly become a hub of central importance in Asia.

The patterns of trade have also shifted toward greater use of global value chains--that is, intermediate products that are shipped across national borders at least once, and often multiple times, before they become final products. Here's the overall pattern since 1995 of falling tariffs and rising participation in global value chains for the world economy as a whole.

Several decades ago, emerging markets around the world worried about having access to selling in US and European markets, and this market access could be used by the US and European nations as a bargaining chip in economic treaties and more broadly in international relations. Looking ahead, US production is now more tied into global value chains, and the long-term growth of US manufacturing is going to rely more heavily on sales to markets outside the United States.

For example, if one is concerned about the future of the US car industry, the US now produces about 7% of the world's cars in 2015, and about 22% of the world's trucks. The future growth of car consumption is going to be primarily outside the US economy. For the health and long-term growth of the US car business, the possibility of unfair imports into the US economy matters a lot less than the access of US car producers to selling in the rest of the world economy.

The interconnectedness of global value chains means that General Motors already produces more cars in China than it does in the United States. In fact, sales of US multinationals now producing in China are already twice as high as exports from the US to China. Again, the long-term health of many US manufacturers is going to be based on their ability to participate in international value chains and in overseas production.

Although what caught my eye in this chapter of the World Economic Outlook report was the shifting patterns of world trade, the main emphases of the chapter are on other themes that will come as no surprise to faithful readers of this blog. One main theme is that shifts in bilateral and overall trade deficits are the result of macroeconomic factors, not the outcome of trade negotiations, a theme I've harped on here (for example, here, here, and here).

The IMF report also offers calculations that higher tariffs between the US and China will cause economic losses for both sides. From the IMF report:

compete in unfettered ways in the increasingly important markets outside the US.

For a sense of the shift, consider this figure from chapter 4 of the most recent World Economic Outlook report, published by the IMF (April 2019). The lines in the figure show the trade flows between countries that are at least 1% of total world GDP. The size of the dots for each country is proportionate to the country's GDP.

In 1995, you can see international trade revolving around the United States, with another hub of trade happening in Europe and a third hub focused around Japan. Trade between the US and China shows up on the figure, but China did not have trade flows greater than 1% of world GDP with any country other than the US.

The picture is rather different in 2015. The US remains an international hub for trade. Germany remains a hub as well, although fewer of its trade flows now exceed 1% of world GDP. And China has clearly become a hub of central importance in Asia.

The patterns of trade have also shifted toward greater use of global value chains--that is, intermediate products that are shipped across national borders at least once, and often multiple times, before they become final products. Here's the overall pattern since 1995 of falling tariffs and rising participation in global value chains for the world economy as a whole.

Several decades ago, emerging markets around the world worried about having access to selling in US and European markets, and this market access could be used by the US and European nations as a bargaining chip in economic treaties and more broadly in international relations. Looking ahead, US production is now more tied into global value chains, and the long-term growth of US manufacturing is going to rely more heavily on sales to markets outside the United States.

For example, if one is concerned about the future of the US car industry, the US now produces about 7% of the world's cars in 2015, and about 22% of the world's trucks. The future growth of car consumption is going to be primarily outside the US economy. For the health and long-term growth of the US car business, the possibility of unfair imports into the US economy matters a lot less than the access of US car producers to selling in the rest of the world economy.

The interconnectedness of global value chains means that General Motors already produces more cars in China than it does in the United States. In fact, sales of US multinationals now producing in China are already twice as high as exports from the US to China. Again, the long-term health of many US manufacturers is going to be based on their ability to participate in international value chains and in overseas production.

Although what caught my eye in this chapter of the World Economic Outlook report was the shifting patterns of world trade, the main emphases of the chapter are on other themes that will come as no surprise to faithful readers of this blog. One main theme is that shifts in bilateral and overall trade deficits are the result of macroeconomic factors, not the outcome of trade negotiations, a theme I've harped on here (for example, here, here, and here).

The IMF report also offers calculations that higher tariffs between the US and China will cause economic losses for both sides. From the IMF report:

US–China trade, which falls by 25–30 percent in the short term (GIMF) and somewhere between 30 percent and 70 percent over the long term, depending on theSome advocates of higher tariffs take comfort in noting that the estimated losses to China's economy are bigger than the losses to the US economy. Yes, but it's losses all around! As the 21st century economy evolves, the most important issues for US producers are going to involve their ability to

model and the direction of trade. The decrease in external demand leads to a decline in total exports and in GDP in both countries. Annual real GDP losses range from –0.3 percent to –0.6 percent for the United States and from –0.5 percent to –1.5 percent for China ... Finally, although the US–China bilateral trade deficit is reduced, there is no economically significant change in each country’s multilateral trade balance.

compete in unfettered ways in the increasingly important markets outside the US.

Tuesday, April 16, 2019

The Utterly Predictable Problem of Long-Run US Budget Deficits

For anyone who can do arithmetic, it did not come as a surprise that the "baby boom generation," born from 1946 up through the early 1960s, started turning 65 in 2010. Here's the pattern over time of the "Daily Average Number of People Turning 65." The jump of the boomer generation is marked.

Because two major federal spending programs are focused on older Americans--Social Security and Medicare--it has been utterly predictable for several decades that the long-run federal budget situation would come under strain at about this time. That figure comes from a report by the US Government Accountability Office, "The Nation’s Fiscal Health Action Is Needed to Address the Federal Government’s Fiscal Future" (April 2019).

Here's a breakdown of the GAO predictions on federal spending for the next 30 years. The "all else" category bumps up about 0.6% of GDP during this time, and normal politics could deal with that easily enough. Social Security spending is slated to bump up about 1% of GDP, which is a bigger problem. Still, some mixture of limits on benefits (like a later retirement age) and a modest bump in the payroll tax rate could deal address this. Indeed, it seems to me an indictment of the US political class, from both parties, that no forward-looking politician has built a movement around steps to "save Social Security."

But the projected rise in government health care spending of 3.2% of GDP is a challenge that no one seems to know how to fix. It's a combination of the rising share of older people, and in particular the rising share of the very-old who are more likely to face needs for nursing home and Alzheimer's care, combined with an overall trend toward higher per person spending on health care. As I've noted before, every dollar of government health care spending represents both care for a patient and income for a provider, and both groups will fight hard against cutbacks.

Meanwhile, this rise in spending, coupled with the assumption that tax revenues remain on their current trajectory, means higher government deficits and borrowing. Over time, this also means higher government interest payments. So if we lack the ability to control the rise in deficits, interest payments soar. In 2018, about 7.9% of federal spending is interest payments on past borrowing. By 2048, on these projections, about 22% of all federal spending will be interest payments on past debt. Of course, this also means that finding ways to reduce the deficit with spending and tax changes also has the benefit that it avoids this soaring rise in interest payments.

As a side note, I thought a figure in the GAO report showing who holds US debt was interesting. The report notes:

The arguments for restraint on federal borrowing are fairly well-known. There's the issue that too much debt means less ability to respond to a future recession, or some other crisis. There's an issue that high levels of federal borrowing soak up investment capital that might have been used more productively elsewhere in the economy. There's a concern that federal borrowing is financing a fundamental shift in the nature of the federal government: it used to be that most of government spending was about making investments in the future--infrastructure, research and development, education, and so on--but over the decades it has become more and more about cutting checks for immediate consumption in spending programs.

But at the moment, I won't argue for this case in any detail, or offer a list of policy options. Those who want to come to grips with the arguments should look at William Gale's just-published book, Fiscal Therapy: Curing America's Debt Addiction and Investing in the Future, For an overview of Gale's thinking, a useful starting point is the essay "Fiscal therapy: 12 framing facts and what they mean" (Brookings Instution, April 3, 2019).

Of course, I personally like some of Gale's proposals better than others. But overall, what I really like is that he takes the issue of rising government debt in the long-run seriously, and takes the responsibility of offering policy advice seriously. He doesn't wave his hands and assume that faster economic growth will bring in additional waves of tax revenue; or that "taxing the rich" is a magic elixir; or that the proportion of older people who are working will spike upward; or that we can ignore the deficit for five or ten or 15 years before taking some steps; or that government spending restraint needs nothing more than avoiding duplication, waste, and fraud. He uses mainstream estimates and makes concrete suggestions. For an outside analysis of his recommendations, John Ricco, Rich Prisinzano, and Sophie Shin run his proposals through the Penn Wharton Budget Model in "Analysis of Fiscal Therapy: Conventional and Dynamic Estimates (April 9, 2019).

As a reminder, here's the pattern of US debt as a share of GDP since 1790. Through most of US history, the jumps in federal debt in the past are about wars: the Revolutionary War, the Civil War, World Wars I and II. There's also a jump in the 1930s as part of fighting the Great Depression, and the more recent jump which was part of fighting the Great Recession.

But the aging of the US population and rising health care spending are going to take federal spending and deficits to new (peacetime) levels. On the present path, we will surpass the previous high of federal debt at 106% of GDP in about 15-20 years. It would b imprudent to wait and see what happens.

Because two major federal spending programs are focused on older Americans--Social Security and Medicare--it has been utterly predictable for several decades that the long-run federal budget situation would come under strain at about this time. That figure comes from a report by the US Government Accountability Office, "The Nation’s Fiscal Health Action Is Needed to Address the Federal Government’s Fiscal Future" (April 2019).

Here's a breakdown of the GAO predictions on federal spending for the next 30 years. The "all else" category bumps up about 0.6% of GDP during this time, and normal politics could deal with that easily enough. Social Security spending is slated to bump up about 1% of GDP, which is a bigger problem. Still, some mixture of limits on benefits (like a later retirement age) and a modest bump in the payroll tax rate could deal address this. Indeed, it seems to me an indictment of the US political class, from both parties, that no forward-looking politician has built a movement around steps to "save Social Security."

But the projected rise in government health care spending of 3.2% of GDP is a challenge that no one seems to know how to fix. It's a combination of the rising share of older people, and in particular the rising share of the very-old who are more likely to face needs for nursing home and Alzheimer's care, combined with an overall trend toward higher per person spending on health care. As I've noted before, every dollar of government health care spending represents both care for a patient and income for a provider, and both groups will fight hard against cutbacks.

Meanwhile, this rise in spending, coupled with the assumption that tax revenues remain on their current trajectory, means higher government deficits and borrowing. Over time, this also means higher government interest payments. So if we lack the ability to control the rise in deficits, interest payments soar. In 2018, about 7.9% of federal spending is interest payments on past borrowing. By 2048, on these projections, about 22% of all federal spending will be interest payments on past debt. Of course, this also means that finding ways to reduce the deficit with spending and tax changes also has the benefit that it avoids this soaring rise in interest payments.

Domestic investors—consisting of domestic private investors, the Federal Reserve, and state and local governments—accounted for about 60 percent of federal debt held by the public as of June 2018, while international investors accounted for the remaining 40 percent. International investors include both private investors and foreign official institutions, such as central banks and national government-owned investment funds. Central banks hold foreign currency reserves to maintain exchange rates or to facilitate trade. Therefore, demand for foreign currency reserves can affect overall demand for U.S. Treasury securities. An economy open to international investment, such as the United States, can essentially borrow the surplus of savings of other countries to finance more investment than U.S. national saving would permit. The flow of foreign capital into the United States has gone into a variety of assets, including Treasury securities, corporate securities, and direct investment.

The arguments for restraint on federal borrowing are fairly well-known. There's the issue that too much debt means less ability to respond to a future recession, or some other crisis. There's an issue that high levels of federal borrowing soak up investment capital that might have been used more productively elsewhere in the economy. There's a concern that federal borrowing is financing a fundamental shift in the nature of the federal government: it used to be that most of government spending was about making investments in the future--infrastructure, research and development, education, and so on--but over the decades it has become more and more about cutting checks for immediate consumption in spending programs.

Of course, I personally like some of Gale's proposals better than others. But overall, what I really like is that he takes the issue of rising government debt in the long-run seriously, and takes the responsibility of offering policy advice seriously. He doesn't wave his hands and assume that faster economic growth will bring in additional waves of tax revenue; or that "taxing the rich" is a magic elixir; or that the proportion of older people who are working will spike upward; or that we can ignore the deficit for five or ten or 15 years before taking some steps; or that government spending restraint needs nothing more than avoiding duplication, waste, and fraud. He uses mainstream estimates and makes concrete suggestions. For an outside analysis of his recommendations, John Ricco, Rich Prisinzano, and Sophie Shin run his proposals through the Penn Wharton Budget Model in "Analysis of Fiscal Therapy: Conventional and Dynamic Estimates (April 9, 2019).

As a reminder, here's the pattern of US debt as a share of GDP since 1790. Through most of US history, the jumps in federal debt in the past are about wars: the Revolutionary War, the Civil War, World Wars I and II. There's also a jump in the 1930s as part of fighting the Great Depression, and the more recent jump which was part of fighting the Great Recession.

But the aging of the US population and rising health care spending are going to take federal spending and deficits to new (peacetime) levels. On the present path, we will surpass the previous high of federal debt at 106% of GDP in about 15-20 years. It would b imprudent to wait and see what happens.

Monday, April 15, 2019

US Attitudes Toward Federal Taxes: A Rising Share of "About Right"

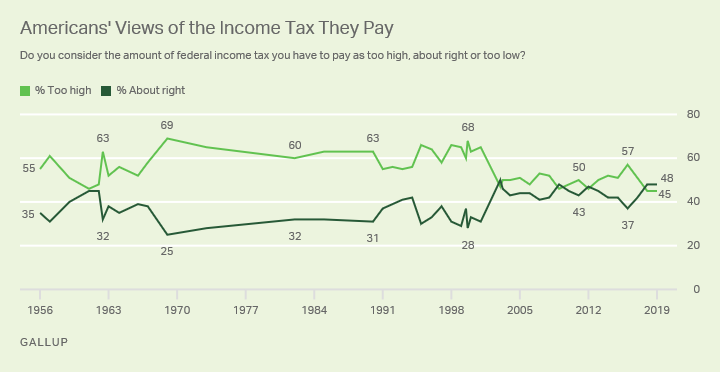

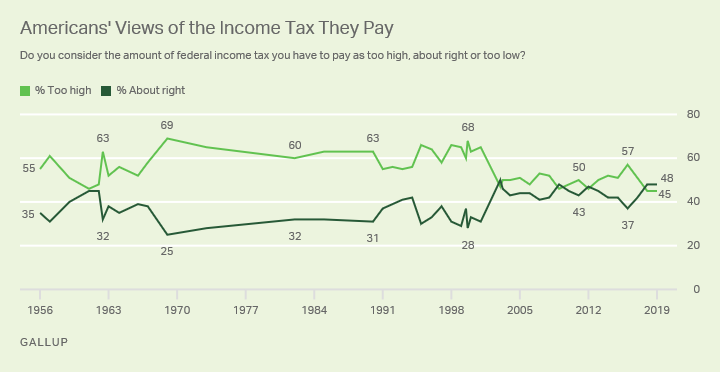

The Gallup Poll has been asking Americans since the 1950s whether they think that the income tax they pay is "too high" or "about right." The figure shows the responses over time including the 2019 poll, taken in early April. (The "don't know" and the "too low" answers are both quite small, and are not shown on the figure.)

What's interesting to me here is that from the late 1960s up through the 1990s, a healthy majority of Americans consistently viewed their income taxes as too high. But since around 2000, the gap has been much narrower. Indeed, the share of Americans saying that their income taxes are "about right" has been at its highest historical level in 2018 and 2019.

In more detailed questions, the Gallup poll also asks different income groups, and whether they are paying too much, a fair amount, or too little. Unsurprisingly, the general sentiment is that those with upper income levels could pay more. But there are some patterns I wouldn't necessarily have expected in the results, as well. Here are the results for what people think about what upper-income people are paying in federal taxes (for readability, I omitted the 2-4% in the "don't know" column):

What jumps out at me is that the proportion saying that upper-income people are paying a fair share of federal taxes was at its highest ever in 2019, while the share saying that upper-income people are paying "too little" was at its lowest ever. Yes, there's still a majority saying that upper-income people are paying "too little." But it's a shrinking majority. Given trends toward greater inequality of incomes over the 25 years shown in the table, I wouldn't have expected that pattern.

Here's the pattern for federal taxes paid by middle-income people:

Here, you can see the pattern from the figure above: that is, the share saying that middle-income people pay too much is falling, while the share saying that they pay their fair share seems to have risen over time.

For the share paid by lower-income people, the pattern looks like this:

Overall, the most common answer is that lower-income people pay "too much" in federal taxes. But it's interesting that the share saying that lower income people pay "too little" is higher than the share saying that middle-income people pay "too little." The share saying that lower-income people pay "too little" in federal taxes was especially high in 2014 and 2015, although it's dropped off a little since then,

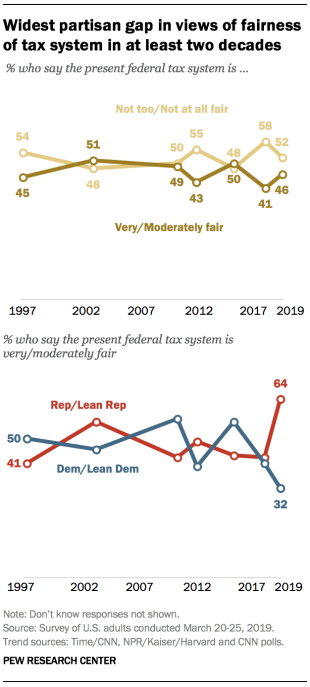

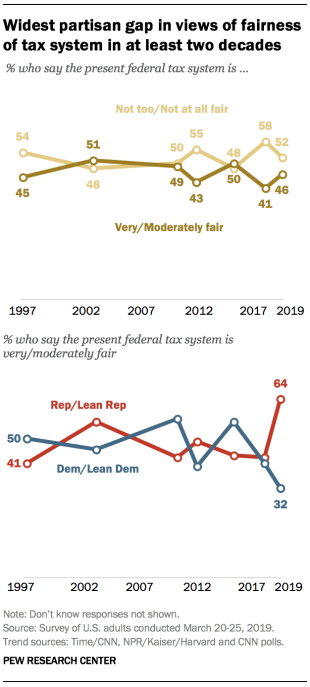

Of course, questions about whether a tax code is fair are going to be influenced by political partisanship. For example, here are some poll responses from the Pew Research Center. Their polling shows that the share of American thinking the federal tax system is very or moderately fair rose overall slightly in the last year overall. However, this modest overall rise is a result of Republicans being much more willing to say the tax system is fair than at any time in the last 20 years, and Democrats being much less willing to say so.

As I've pointed out in the past, poll responses on economic questions like whether free trade offers benefits are also influenced dramatically by political preferences. During the past couple of years, as President Trump has inveighed against international trade and called for protectionism, Democrats have suddenly become much more positive about trade. One suspects that this pattern emerged more from anti-Trump feeling than from increased time spent reading economics textbooks.

Still, it's interesting to me that a plurality of American now see the federal income tax as "about right," while the proportion saying that upper-incomes pay too little is down, the proportion saying that middle-incomes pay a fair share is up, and the proportion saying that lower incomes pay too little has risen. Perhaps politicians who call for cutting taxes, or for dramatic tax increases, are refighting battles from the 1990s that are of less relevance to current voters.

What's interesting to me here is that from the late 1960s up through the 1990s, a healthy majority of Americans consistently viewed their income taxes as too high. But since around 2000, the gap has been much narrower. Indeed, the share of Americans saying that their income taxes are "about right" has been at its highest historical level in 2018 and 2019.

In more detailed questions, the Gallup poll also asks different income groups, and whether they are paying too much, a fair amount, or too little. Unsurprisingly, the general sentiment is that those with upper income levels could pay more. But there are some patterns I wouldn't necessarily have expected in the results, as well. Here are the results for what people think about what upper-income people are paying in federal taxes (for readability, I omitted the 2-4% in the "don't know" column):

What jumps out at me is that the proportion saying that upper-income people are paying a fair share of federal taxes was at its highest ever in 2019, while the share saying that upper-income people are paying "too little" was at its lowest ever. Yes, there's still a majority saying that upper-income people are paying "too little." But it's a shrinking majority. Given trends toward greater inequality of incomes over the 25 years shown in the table, I wouldn't have expected that pattern.

Here's the pattern for federal taxes paid by middle-income people: