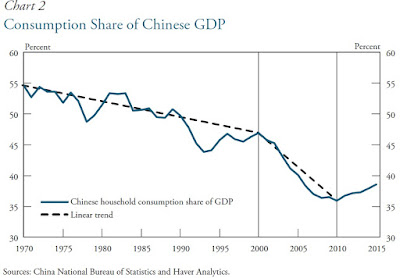

"After steadily declining for nearly half a century, the share of consumer spending in China’s GDP has recently increased. Economists and policymakers widely agree that the share of consumer spending must increase for China to continue its economic development; sustaining growth primarily on exports and investment will become more difficult in the longer run. ... Although the recent rise in the consumption share has allayed some concerns about slowing growth in China, it has also spurred discussion over whether this trend is sustainable and whether China will truly become a consumption-driven economy."To put China's low consumption patterns in perspective, it's useful to remember that in the US, about 65% of GDP is usually accounted for by consumption. In China, consumption was only about half of GDP in 1970s and 1980s--and then the share dropped even lower, falling below 40% of GDP. What's happening here is that China's consumption was growing, but GDP was growing even faster, so the ratio of consumption/GDP was falling, right up until about 2010.

Nie and Palmer discuss the evidence from economic research on what caused China's consumption to fall so low, and whether the modest rise of the last few years seems likely to continue. They focus on a few factors that have been evolving over the decades: the age distribution and "dependency ratios" in China's population, the trend to urbanization, and China's housing boom since around 2000--which is about when the consumption/GDP ratio plummeted even lower. I'd summarize their story this way.

The "dependency ratio" refers to what share of the population is either too young or too old to work, as opposed to being working age. The dependency ratio and consumption tend to rise and fall together. Thus, the dramatic fall in birthrates in China as a result of economic growth (and greater education and incomes for women) along with the one-child policy meant a lower dependency ratio. Basically, fewer children means less consumption spending on children, and more saving.

China has seen a dramatic rise in urbanization. As Nie and Palmer write: "Over the past five decades, the share of China’s population living in urban areas has more than tripled, rising from 18 percent in 1960 to 56 percent in 2015." The common pattern is that people moving to urban areas in emergin economies increase both their production and their consumption, but they increase production by more, and so their rate of saving rises.

Nie and Palmer look at patterns of dependency ratios and urbanization across a "sample of 24

countries including most Asian countries and large developing countries." Based on the common patterns, they find that China's fall in consumption/GDP ratio from 1970-2000 is almost completely explained by changes in its dependency ratio and urbanization. But the additional drop in consumption/GDP after 2000 is not explained by these patterns, and they instead attribute this fall to a shift in China's housing market. Here's their explanation (citations and references to charts omitted):

"The large jump in the household saving rate from 2000 to 2010 is largely related to development in China’s housing market during this period. Before 1998, most Chinese families lived in government-provided houses; after economic reforms in 1998 removed this benefit, however, most Chinese families needed to buy their own homes. This change triggered rapid growth in the Chinese real estate sector, causing home prices to rise tremendously. Furthermore, as house prices started to increase quickly, housing became a popular investment for wealthy Chinese households, raising demand even further and exacerbating house price increases. Indeed, from 2000 to 2010, house prices

in China increased by about 161 percent. In addition to rapidly increasing prices, Chinese homebuyers faced large required down payments—typically 30–40 percent, but in some major cities as high as 50 percent. As a result, middle-class Chinese households were forced to save a disproportionately large share of their earnings to purchase a home. The saving didn’t end with the purchase of a home—the subsequent mortgage payments constituted additional saving as they increased the homeowners’ housing equity. As Rosenzweig and Zhang argue, this housing market dynamic helps explain the rising saving rate associated with rising housing prices from 1998 to 2010.

"As the scramble to buy homes after the 1998 reform faded, so, too, did the desire to save for homes. Moreover, young people currently do not need to save as aggressively as the previous generation for home purchases because their parents and grandparents often help them buy a home. Due to the one-child policy, which was introduced in 1979, a typical young couple in China are the sole descendants of four parents and eight grandparents. In China, it is common for parents and grandparents to help their children by paying the high down payment or even paying for the entire house. Small family sizes under the one-child policy allow families to focus their resources rather than spreading them among multiple children or extended family members.

"Large financial contributions from older generations are feasible for two additional reasons. First, after aggressively saving for several decades, many parents and grandparents are wealthy enough to afford this gift to the younger generation. Second, many households own multiple homes. Based on the 2014 China Household Finance Survey, one out of five urban households owns a second home, meaning that on average, a young couple’s parents and grandparents have one extra home between them in addition to their primary residences. Overall, less pressure for young Chinese couples to save helps explain why the Chinese saving rate has started to decline since 2010."

What do these factors imply for the future? China's old-age population is beginning to rise, and in October 2015 China's government announced that it was shifting to a "two-child policy." China's dependency ratio seems set to rise, which should cause consumption to continue rising. Urbanization in China also seems likely to continue, which has tended to hold down consumption in China. The original huge boost in saving from the shift to private housing market has largely run its course (although whether the ongoing boom in China's housing prices is sustainable is different issue). Mixing this together and stirring a few times, Nie and Palmer suggest that China's consumption/GDP ratio will keep rising in the next few years, perhaps to between 45-50% by 2020--that is, to say, almost back to levels prevailing in the 1980s.

When economists and policymakers talk about "rebalancing" China's economy toward faster growth of domestic consumption, I think they have a bigger shift in mind. Nie and Palmer describe the changes in China's household spending this way:

"[R]eal [household] spending on transportation and communication increased sevenfold over the last two decades compared with a threefold increase in overall household spending. Transportation and communication is a broad category that encompasses many high-end goods and services that have recently become available to middle-class Chinese households, such as smartphones, laptops, and air travel. Travel services in particular appear to be growing quickly: the number of Chinese outbound travelers has been growing at a double-digit pace for many years, and 2015 marked the fourth consecutive year of China as the world’s top tourism source market ... [A]nother component of consumption, educational services, is also growing rapidly. Chinese families now are spending more resources on their child’s education both inside and outside the classroom. In addition to paying tuition both domestically and at foreign colleges and universities, Chinese families are increasingly paying for tutoring and other educational supplements for their children."If China's government wishes to boost consumption, it could do more to encourage spending in areas like education and health care, as well as to support consumption and health services for its growing population of elderly.